Singing the Blues About Water Scarcity

Otis Redding sang “you don’t miss your water ’til your well runs dry” in 1965 about pining for a lost love. Last week, Climate and Society founder and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory scientist Mark Cane reprised it with a much different, more literal focus: water scarcity in the 21st century.

A version of this post originally appeared on the Climate and Society Hot Topics blog.

Otis Redding wraps up his acclaimed 1965 album Otis Blue with “You Don’t Miss Your Water.” The refrain “you don’t miss your water ’til your well runs dry” was originally written by William Bell and inspired by his feelings of homesickness for his native Memphis while in New York. In Redding’s rendition, it feels more like he’s singing about a lost love. The chameleon nature of the sentiment is perhaps why it showed up at the State of the Planet conference on Thursday at Columbia University.

Climate and Society founder and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory researcher Mark Cane opened his remarks with that refrain. Cane was speaking on a panel about water scarcity at the conference, a semi-annual event sponsored by the Earth Institute. The reference wasn’t about lost love or home but rather our global water resources. Though the well hasn’t run dry yet, water scarcity is a growing concern from large cities in the American Southwest to smallholder farmers in Vietnam. Even New York, which is traditionally thought of as water secure, might have its own set of concerns in the coming decades.

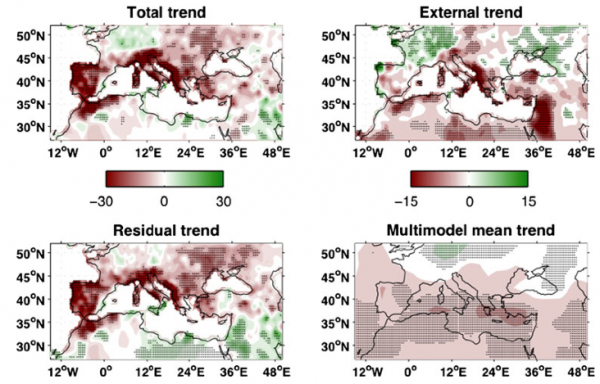

Cane highlighted Climate and Society alum and current PhD candidate Colin Kelley’s work in the eastern Mediterranean to show how concerns can translate into unrest. Kelley is working with Cane and others to examine how climate change ties into the recent strife in Syria.

“There’s been a horrific drought in Syria, particularly over the last five years,” Cane said. Just how horrific? It’s a drought that has no parallels over the last century. It has lasted for five years, with 2007-08 being the worst drought on record. Overall, the winters, Syria’s main growing season, from 2004 through 2009 were the driest five-year period on record for the region.

“Syria is thought of as a dry country but it actually receives a fair amount of winter rainfall along its Mediterranean Sea coast and in the northeast ” Kelley explained in an interview about his research. “This is the Fertile Crescent. Farmers have access to water from the Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers. Though there were periods in the past when it would get dry there, they weren’t prepared for this.”

That unpreparedness has societal and policy roots, but a changing climate is also to blame. “This is a place where the drying is highly likely a consequence of global warming,” Cane explained. Deconstructing the rainfall patterns based on the patterns of the North Atlantic Oscillation, a climate pattern which influences precipitation in the Mediterranean, a climate change signal reveals a change happening in Syria that is unlikely to be due to natural variability alone.

“I’m not going to attribute the conflict in Syria to drought, but the drought has driven farmers into the cities and has certainly created conflict there,” Cane said. Kelley further noted, “It’s not hard to see it as a contributing factor since people’s basic human needs weren’t being met.”

The ensuing chaos that has roiled Syria points to one of Cane’s essential worries: “It’s very difficult to get people to act before the well runs dry, but times of crisis may not lead to the most rational decisions.”

The crisis management mindset is clear on an international level: only Australia has a comprehensive drought plan in place that emphasizes risk preparedness ahead of crisis management. Even that plan, which was born in 1992 during a fouryear drought that cost Australia economy $5 billion, is not without its detractors (pdf).

However, after a 2009 review, a pilot project to improve the plan was implemented in western Australia. It gives a glimpse of what a stronger drought preparedness plan could look like. Features such as helping communities and individual farms build social capital, adapt lands to a changing climate, assistance for farmers looking to leave the profession and an effective water market will help weather the storm (or lack thereof).

Even these policies will need revisions according to a review (pdf) of Australia’s updated drought plan. That doesn’t mean it isn’t on the right track, though. Quite the opposite according to Cane. “You have to think about unintended consequences,” he said. “You have to come at it with humility and be prepared to adjust along the way.”