Rosanne D’Arrigo: Decoding The History of Climate Cycles, One Tree Ring At A Time

A simple fascination with winter and weather patterns led D’Arrigo to become a globe-trotting scientist who collects and analyzes important data from tree rings.

Rosanne D’Arrigo, a research professor of biology and paleoclimate at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University, started out as one of the very few women who ventured into dendrochronology — the scientific study of dating tree rings to figure out when they were formed. Deriving data from those tree rings allows her to study the climate and atmospheric conditions that existed thousands of years ago.

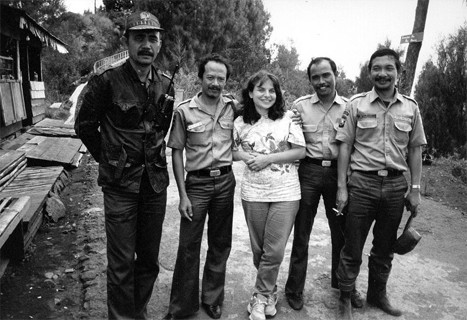

D’Arrigo’s work in collecting these valuable tree rings has taken her to remote locations in countries like Myanmar, Canada, Alaska, Indonesia, Madagascar, Mongolia, and Japan, to name a few. Her extensive research has involved studying the complexity of different components of the Asian monsoon and how volcanoes can play a role in cooling the tropics. In an email conversation with State of the Planet, she explained her career path and observations from some of her recent studies.

How did you end up becoming a climate scientist?

I grew up in the Bronx in Pelham Parkway. As a New Yorker, I was always a winter weather enthusiast. During winters, we used to have tons of snow and have to shovel it all the time and stay home from school. So, that always vaguely made me want to do something [professionally] with weather.

How and when did you start studying tree rings?

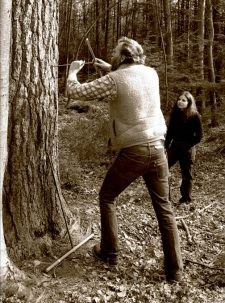

After getting my bachelors and a masters in biological sciences at the State University of New York at Binghamton, I moved back to NYC. One of my other interests since college was botany and plant anatomy. But, back then, there were not that many opportunities in New York City. I then became aware of the Tree-Ring Laboratory through researching old Lamont yearbooks while I was looking for a way to follow my interests. They were looking to find their first graduate student, which ended up being me. I was able to combine weather and botany, which made me very happy. Pursuing such a PhD program was kind of like the Wild West in those days.

Back then, what were some of the challenges you faced in pursuing dendrology and dendrochronology?

During my time researching old Lamont yearbooks, I met the director of the Tree Ring Lab at the time, Gordon Jacoby [now deceased], because he was looking for a graduate student. Back then, to become a grad student in tree rings at Lamont, I needed to jump through some hoops because at the time you were expected to be a geologist to get a PhD there.

So, one challenge was being new to it all and taking graduate courses in geology when I didn’t even know what an igneous rock was! Nor were there many classes on the topics that I needed and wanted to learn more about. But I was able to take some climate courses at Goddard Institute for Space Studies and one of my advisors, Inez Fung, was an atmospheric modeler. That opened up my perspective.

Another challenge was that there were very few women in the field in those days, so it got a bit lonely in that regard. Luckily, I had great friends in my year and they helped me with the math and hard rock stuff. I also had a really great mentor. That was absolutely essential for me.

You have carried out extensive research work on the Asian monsoon. With new data that became available to test climate models in the last decade, what are some common misconceptions about rainfall in Southeast Asia?

Not a misconception necessarily but something that became clearer to us while working on this long-term project was just how complex the Asian monsoon is and all of its different components and seasonal variabilities. This makes things difficult when you are studying an area where there are mixed elements of the monsoon. Our study illustrated that volcanism can affect rainfall patterns over the Asian region. We are still in the process of understanding other underlying and interacting factors.

Complicating matters such as these add to the difficulty of studying tropical tree rings relative to those at higher latitudes. There are fewer species that are suitable for dendrochronological dating. There is also a dearth of well-defined seasonality that allows annual growth rings to form and to be distinct.

Your recent study on Scottish tree rings details an extremely cold period in Scotland in the 1690s that killed 15 percent of the population and severely damaged crops. Do you predict it is likely that the country might have to withstand another similarly bone-chilling winter in the future?

It is hard to say for sure. Most certainly there will be climatic extremes, although, with global warming we would expect fewer cold ones. However, there could be some not entirely foreseen climate surprises. For example, the Day After Tomorrow scenarios, where the ocean’s conveyor belt can shut off and could cause another ice age!

One of your previous studies found that volcanoes can cool the tropics as volcanic particles reflect sunlight back into space. But, with rising global temperatures, those cooling effects have been reversed. Do you believe geoengineering, such as releasing or injecting sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere, can offer some hope in the future?

This has been talked about for decades. The main question will be figuring out the amount, and nature of the material released and where, and under what conditions. Those variables are hard to control.

What has been your most memorable or exciting field trip while studying tree rings on the field?

My most memorable was my first trip to the Thelon River Sanctuary in central Canada in 1984. I had never really been to a true wilderness area before and this one was about a three-hour flight by charter plane from Yellowknife. So, it was quite remote. Lots of great old white spruce and some larch trees. I saw a herd of muskoxen, the resident wildlife, along with wolves, bears, and other wildlife. There are also the ruins of a cabin that the explorer John Hornby died of starvation in.

What research work or projects are you currently working on?

Right now we are focusing on a research and education project called PIRE from the National Science Foundation that spans the western Americas. We are collecting tree ring and cave data to reconstruct the monsoon and El-Niño Southern Oscillation [an irregular and periodic change in winds and sea surface temperatures over the Eastern Pacific Ocean] over the past thousand years. Other projects include studying the boreal forests in North America and analyzing past climate and growth changes in these forests’ trees.