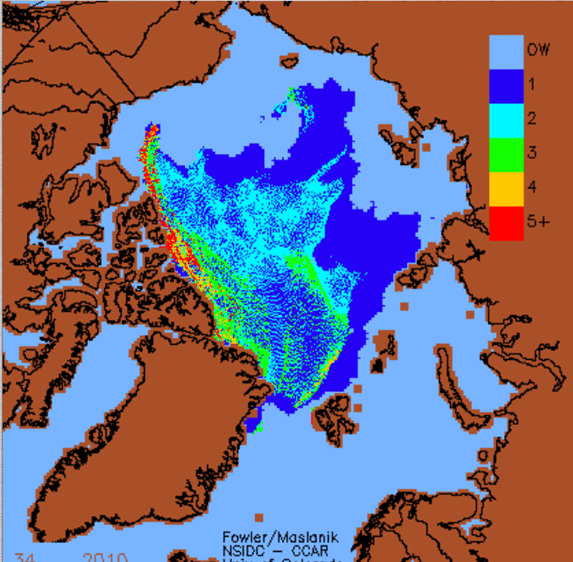

Studies of ice formation patterns, water currents, winds and the arrangement of arctic land masses has led the scientists to project that even as summer sea ice nearly disappears from the northern ocean by about 2050, floes will continue to pile up and persist along the northern flanks of the Canadian Archipelago and Greenland. This region is currently clogged with heavy ice, some of it drifting in from as far away as Siberia.

“We wanted to look at the tail end–what will happen after the arctic moves to largely ice-free state?” said Pfirman. “Where will the [last] ice be located? If it collects in one area, it could maintain a sea-ice ecosystem for decades.” Brendan Kelly, a polar biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Juneau, Alaska, explored the ecological implications, but cited potential problems, including declines in the snow cover needed by seals, and the genetic dangers of having declining populations of rare creatures crammed into shrinking areas. Bruno Tremblay, a climatologist and oceanographer at McGill University, in Montreal, ran an animation showing the shrinkage of warm-season sea ice in the recent past, and a projection into the future . The scientists said that sea ice will continue to cover the ocean in the winter for the foreseeable future–but that arctic creatures need the ice during warmer seasons as well to breed and eat.

Newton said that if there is to be a remnant area, the “first step” is to identify where it might be. With this information, a wide community of governments and native peoples would then at least have information available to consider whether or how to manage such a place in the face of shipping, oil exploration, tourism and other activities that are expected to increase as the arctic becomes more accessible. “We’re hoping to provoke this conversation,” said Newton.

Watch the press conference

Read the news reports in:

Nature

Discovery News

The Christian Science Monitor

Associated Press

USA Today