Land Subsidence in the Netherlands

At a symposium on land subsidence, I learned about how the Dutch transformed their country so that about a quarter of it is below sea level and how they cope with it.

I usually only write a blog when I go to do fieldwork, not when I’m going to a meeting. However, this time the meeting was the Tenth International Symposium on Land Subsidence (TISOLS) held in Delft and Gouda, Netherlands. Besides meeting others working on land subsidence around the world, I also got to learn and see more about how the Dutch transformed their country so that about a quarter of it is below sea level. As they say: “God made the Earth, but the Dutch made the Netherlands.”

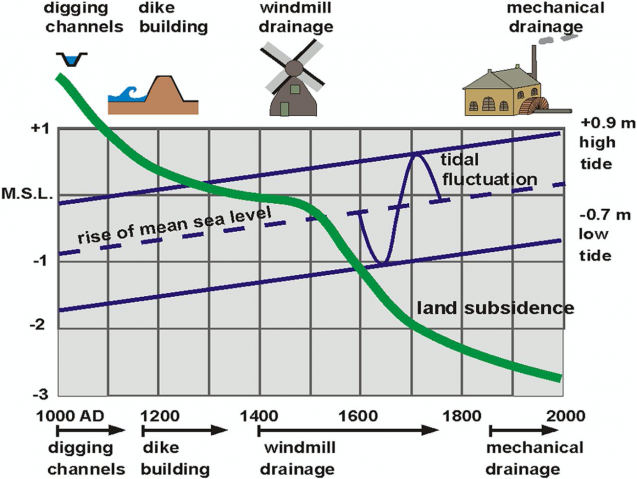

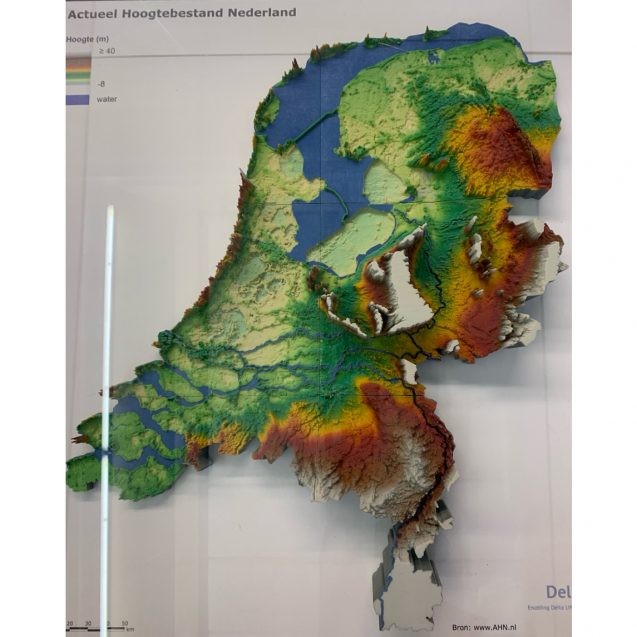

The story begins about a thousand years ago with the introduction of the heave or mouldboard plough. It was capable of turning the heavy organic-rich peaty soils of the Netherlands. To improve drainage, the Dutch began digging channels. However, draining the land exposed the peats to air and they oxidized, turning most of the soil into CO2 and water. The land subsidence led to deeper and larger channels, and then to windmills to pump out the water. They also mined the peat for fuel. The deepest areas are where peat was mined in the past — some more than 22 feet below sea level. The low subsided areas were best as meadows leading to cattle raising and the Dutch cheese industry. The dikes, cheese and windmills of the Netherlands are all the result of land subsidence.

I started my journey in Wageningen in the middle of the country, where I joined several colleagues — Carol Wilson of LSU, Steve Goodbred on Vanderbilt University, and Liz Chamberlain of Wageningen University — to work on a paper about Bangladesh. We also visited a windmill near the historic city center that is still being used to grind flour. Carol and I also bicycled out to the Nederrijn (Lower Rhine) River. We crossed the embankment that protects the town and saw the open pasture fields that protect the city by accommodating any flood waters.

After the weekend in Wageningen, Carol and I went off to the city of Delft with its many canals for the symposium. Our hotel was in the old city. Comprised of four old buildings, I had to go up and down multiple stairs to walk to my room as the floors of each building were at different levels. We had a 20-minute walk to the university for the meeting.

We had presentations and posters on Monday, Wednesday and Thursday. I presented my research on subsidence in Bangladesh on Thursday. On Tuesday, we had multiple field trips. I joined the one that went to Zegveld in the middle of the subsiding area of the western Netherlands. The first stop was an old peat excavation area that is now a set of lakes. It has been turned into a nature preserve, perhaps growing new peat to raise the land.

The next stop was an environmental research station and farm. Here they have equipment to measure the land subsidence and sediment compaction, CO2 and methane emissions, and can experiment with different water levels and crops. I’d like to install some of this equipment in Bangladesh. After a Dutch lunch with soup and cheese sandwiches, we headed to the villages of Kanis and Kamerik. This was our introduction to problems of land subsidence in cities and villages.

We learned that many buildings are built on different pilings. Shallow ones may end in the oxidizing peat, deeper ones in the stronger sand beneath. Some are wooden, and can rot if exposed to air; newer ones are concrete. At the 19th century church, the deep piles keep it from subsiding, but the roads and parking lots are sinking. The roads in the village were recently raised to compensate. However, the weight of the meter of new material will cause compaction of the underlying peats.

They cannot stop the ongoing land subsidence in the Netherlands — they can only control it to limit it to 3-5 millimeters per year. Water levels in the country are carefully controlled by water boards, elected by the people since the 1400s. They are the oldest democratic institution in the country. Everywhere there is a balance of keeping water levels low to prevent flooding and high to prevent subsidence.

The importance of this issue was highlighted on Friday went we went to Gouda for a “Subsidence and Society Day” in the historic Sint Jans Church in the center of town. The church itself is warped by differential subsidence of its two sides. There were talks and presentations, interviews, and panel discussions. A focal point was the official opening of the Kenniscentrum Bodemdaling en Funderingen or Knowledge Centre on Land Subsidence and Foundations in Gouda. This is something hard to imagine outside of the Netherlands, a country whose very name means low-lying lands.

The day ended with a walking tour in which we visited the older buildings and canals of the city. The land by the river, with its sandy deposits is much higher than the parts of the old city built on peat and anthropogenic deposits. The current plan, not welcomed by all, is to hydrologically separate part of the older city with locks and pumps to lower the water level about 10 inches.

Although this was a scientific conference, the field trips and Subsidence Day made it worth posting a blog about it. The entire week was spent either near or below sea level. Between the sinking land and rising seas, soon even more of it will be below sea level. It was impressive to see how much water in the Netherlands is an actively managed system, with water levels carefully controlled by dikes, locks and pumps. It is only because the Netherlands is a wealthy country that so much land below sea level can be maintained.