International Team to Drill Deep Through Antarctic Ice Into Ancient Sediments

The research project, dubbed SWAIS 2C, will investigate the sensitivity of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to global warming of 2 degrees Centigrade.

Researchers are preparing to drill through ice into sediments beneath the ocean floor deep below Antarctica’s Ross Ice Shelf to find out if carbon dioxide emissions targeted in international climate negotiations will head off catastrophic melt of the icy continent.

The research project, dubbed SWAIS 2C, will investigate the sensitivity of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to global warming of 2 degrees Centigrade. Scientists will retrieve sediments from beneath the ice in a bid to find out how the ice behaved during times in the past when temperatures were as warm as those expected in the coming decades. These records could reveal if there is a tipping point in our climate system when large amounts of land-based ice melts, causing oceans to rise swiftly. The West Antarctic Ice Sheet alone holds enough ice to raise sea levels by 4 meters, or about 12 feet.

The SWAIS 2C team includes some of the world’s top Antarctic scientists, led by Richard Levy of New Zealand’s GNS Science, Te Herenga Waka of Victoria University of Wellington, and Molly Patterson of New York’s Binghamton University. In all, researchers from seven U.S. universities will participate. Glaciologist Jonathan Kingslake, geodynamicist Jacqueline Austermann and paleoclimatologist Benjamin Keisling from Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory are part of the team and will perform ice sheet and solid earth modeling to interpret the sediment cores.

The effort is supported by $3.2 million from the U.S. National Science Foundation, with the bulk of the funding going to a team of early-career scientists and postdoctoral researchers. More funding is coming from New Zealand, Germany, Australia, the United Kingdom and the Republic of Korea, with several other nations planning to join. The International Continental Scientific Drilling Program has also awarded the project a $1.2 million grant, the first for an Antarctic drilling program.

The other U.S. institutions involved are Colgate University, Northern Illinois University, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Central Washington University and Rice University.

“We have formed a team of drillers, engineers, field experts and scientists who are up to the task. Discoveries will show us how much the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could melt if we miss Paris Agreement targets,” Levy said.

Patterson said geological data can provide direct evidence of ice extent during past periods. “This information is necessary to assess whether climate models are able to capture observed variability during warmer times in Earth’s history prior to making any assumptions about the future,” she said.

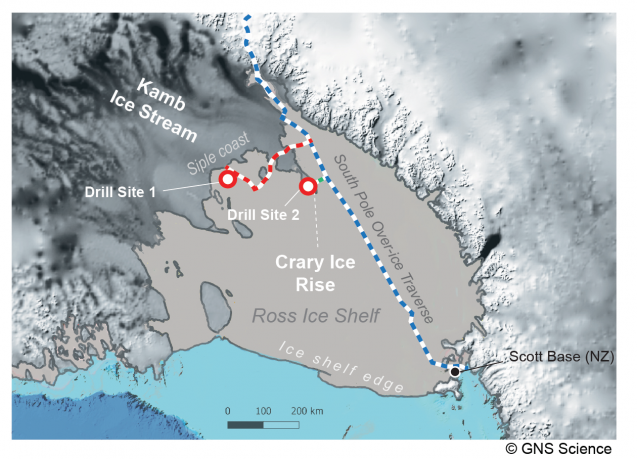

When the field campaign kicks off, preparation teams will depart from Scott Base in mid-November for a 1,200-kilometer traverse across the Ross Ice Shelf to the Siple Coast, where land ice meets the ocean and starts to float. Once a drilling camp has been established, the wider science team including the Lamont-Doherty researchers will join the group and work through February. Field campaigns are planned for the next three years.

No one has ever drilled into the Antarctic seabed at a location so far from a major base, nor so close to the center of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Engineers at Victoria University of Wellington’s Antarctic Research Centre have spent four years developing technology capable of hot-water drilling through an estimated 800 meters of ice before taking sediment samples from up to 200 meters beneath the ice sheet. The sediments should help scientists understand how much Antarctic ice melted when the world’s climate was warmer, and allow them to predict what might happen in the future if global temperatures continue on their current trajectory toward 2.7 degrees C above pre-industrial levels.

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet is considered highly vulnerable to climate change because much of the ice, which rests on bedrock thousands of meters below sea level, is exposed to the warming waters of the Southern Ocean. The international scope of the project highlights the recognition by multiple nations and science funding agencies that understanding its fate remains one of the largest uncertainties in predicting the global foot print of future sea level rise, said the researchers.

Adapted from a press release by the SWAIS 2C project.

RELATED:

Antarctica and future sea level rise projections

Ice sheet loss in Western Antarctica over the past 16 years

Collapse of West Antarctica’s ice sheet is avoidable if warming is below 2°