Extreme-Weather Winters Becoming More Common in U.S., Study Shows

This past July was Earth’s hottest month since record keeping began, but warming isn’t the only danger climate change holds in store. Recent years have seen a dramatic increase in the simultaneous occurrence of extremely cold winter days in the Eastern United States and extremely warm winter days in the Western U.S., according to a new study.

This past July was Earth’s hottest month since record keeping began, but warming isn’t the only danger climate change holds in store. Recent years have seen a dramatic increase in the simultaneous occurrence of extremely cold winter days in the Eastern United States and extremely warm winter days in the Western U.S., according to a new study. Human-caused emissions of greenhouse gases are likely driving this trend, the study finds.

In the past three years alone, heat-related drought in the West and bitter cold spells in the East have pinched the national economy, costing several billion dollars in insured losses, government aid, and lost productivity. When such weather extremes occur at the same time, they threaten to stretch emergency responders’ disaster assistance abilities, strain resources such as inter-regional transportation, and burden taxpayer-funded disaster relief.

Understanding the physical factors driving extreme weather could provide decision-makers with more reliable information with which to prepare for weather disasters, while understanding the likelihood of droughts could help engineers better plan the development and management of infrastructure to provide reliable water supplies.

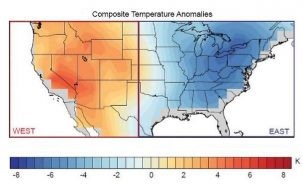

The new study, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, finds that the occurrence and severity of “warm-West/cold-East” winter events, which the authors call the North American winter temperature dipole, increased significantly between 1980 and 2015. This is partly because winter temperature has warmed more in the West than in the East, but the authors found that it also has been driven by the increasing frequency of a “ridge-trough” pattern, with high atmospheric pressure in the West and low atmospheric pressure in the East producing greater numbers of winter days with extreme temperatures in large areas of the West and East at the same time.

“What we’ve found is that this particular atmospheric configuration connects the cold extremes in the East to the occurrence of warm extremes ‘upstream’ in the West,” said lead author Deepti Singh, a post-doctoral research scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

Despite long-term warming across most of the globe, some regions can experience colder than normal temperatures associated with anomalous circulation patterns that drive cold air from the poles to the mid-latitudes. In fact, circulation patterns that facilitate such extremes are potentially a response to enhanced warming, the authors point out.

“Although the occurrence of cold extremes is often used as evidence to dismiss the existence of human-caused global warming, our work shows that the warm-West/cool-East trend is actually consistent with the influence of human activities that have modified Earth’s climate in recent decades,” Singh said.

Looking back at 35 years of temperature data, the scientists found that the winters of 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 had the greatest differences between the U.S. East and U.S. West. Much of the Western U.S. was exceptionally warm and dry, with record-low soil moisture and mountain snowpack, while the Eastern U.S., faced bitter cold spells and blizzards.

The simultaneous occurrence of extreme Western warmth and extreme Eastern cold will likely decrease over time as warming reduces the occurrence of cold winters in the East. Still, the researchers project that some extremely cold events will still occur even with high levels of global warming.

“We can absolutely expect further increases in hot events if global warming continues,” said co-author Noah Diffenbaugh, an associate professor in Earth System Science at the School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences and a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. “But our results also highlight how complex climate change can be. We should be prepared for both warm and cold extremes – sometimes simultaneously – now and in the future.”

Other coauthors of the study are Justin Mankin of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, Daniel Horton of Northwestern University, and Daniel Swain of the UCLA, who along with Singh are former members of Diffenbaugh’s research group; and Professors Leif Thomas and Bala Rajaratnam of Stanford.

This article is adapted from a release written by Rob Jordan of Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save