Emotional Appeal: How Art Can Inspire Action on Climate Change

Climate science tells us how the world is changing. Climate art shapes how we choose to respond.

In honor of Earth Day on April 22, the Earth Institute has a variety of great stories and events lined up for you throughout the entire month of April. Learn more.

It was on a trip to Greenland that artist Zaria Forman first grasped the urgency of the climate crisis. She was traveling with her family and, having never been to a polar region before, planned to use the landscape as inspiration for her work. The hotel they were staying at was bustling, not with tourists, but with government officials, newscasters, and scientists — all there to study the Greenland ice sheet. In 2007, most media outlets in the United States weren’t covering climate change. But in the Arctic, a then-record 552 billion tons of ice was melting — the equivalent of eight Olympic swimming pools draining into the ocean every second.

Forman remembers speaking with the scientists over dinner about what they were seeing. “It really clicked for me,” she said. “Climate change is one of the largest crises we face as a global society, and there wasn’t a question in my mind that it was what I needed to focus on.”

Forman is part of a growing movement of artists using their work to address and convey the magnitude of the climate crisis. Earlier this month, she and several others participated in two panel events hosted by the Earth Institute and Mana Contemporary on how art and science can work together as a vehicle for climate action.

Artists as Witnesses

The work of these artists, not unlike science itself, takes root in the careful observation of the natural world. “When you draw something, you are forced to examine and re-examine it very closely,” said James Prosek, whose documentation of fish species has taken him from the base of California’s Mount Whitney to the headwaters of the Euphrates River in Turkey. Much of Prosek’s work explores the artificial boundaries that people have constructed to define nature — not only by drawing geographic borders, but also by relying on conventions like taxonomy.

“Nature is this interconnected, constantly changing system,” said Prosek, “but in order to communicate it, we have to reduce it. We draw lines between things and label them as pieces.” He explained that while the reduction of nature is a critical part of building knowledge — calling a Gila trout a Gila trout helps differentiate it from an Apache trout — it also creates a tendency for people to lose sight of the larger whole, especially in the face of universal threats like climate change.

Art offers a way to challenge that tendency, in part by sharing other representations of the natural world. “My work has always been about giving viewers a chance to experience a place they might not have the chance to visit,” said Forman. Her pastel drawings — so detailed that they are often mistaken for photographs — are like windows cut into the gallery walls, opening out to Earth’s most remote and threatened environments. It is by relaying the beauty of these places that Forman hopes to instill in others the same deep love of landscapes that she has known since childhood. “When you love something, you want to protect it,” she said.

Bridging Fact and Emotion

The psychology behind public engagement suggests that the visual narratives provided through art help people process, internalize, and respond to information more effectively than facts alone. By molding their experiences into an opportunity for emotional connection, artists form a keystone between the viewer and the changing climate.

Forman first sought to do this through capturing the ice. For artist Jeff Frost, it began with wildfire — or, more accurately, 70 different wildfires over the span of five years. His compilation of this footage, a 25-minute film entitled “California on Fire,” is structured around the five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, sadness, and acceptance. With each one, the intangibility of the climate crisis becomes something familiar — its vastness, personal.

“My feeling is that if you make art that is trying to be didactic first, it probably won’t be very good art,” said Frost. “I primarily try to connect with people’s hearts and curiosity.”

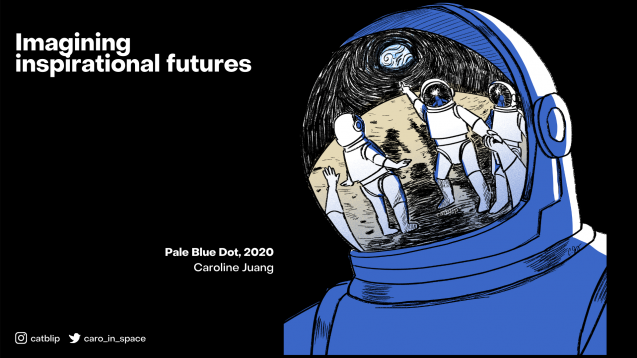

It is a distinction that Caroline Juang knows well, both as an artist herself and a Ph.D. student with Columbia University’s Department of Earth and Environmental Science and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. Her research involves analyzing the steady increase of burned forest area in the western United States. “Science is there to give the information, to support this idea of climate change,” said Juang. “With Jeff’s film, it’s almost as if your house is burning down, or if your house is not burning down, that you’re the firefighter.”

Turning Emotion into Action

Frost will be the first to acknowledge that equitably and comprehensively addressing the climate crisis requires structural change. Behind any structural change, however, is the relentless and ongoing effort to demand a better future.

“Artists can’t directly make policy,” he said, “but we can help influence other people, including the politicians themselves.”

As for what to do upon being inspired by a piece of art, Forman and Frost agree there is no one way to approach climate action. “It’s about figuring out what your sharpest tool is,” said Forman. “When what you do is really coming from the heart — coming from you — then that is where you can move people the most.”

Art by Zaria Forman, James Prosek, and Jeff Frost is on display at Mana Contemporary from April 22 to July 22 as part of the exhibition, “Implied Scale: Confronting the Enormity of Climate Change.”

To help advance the work of climate scientists and experts working on our most pressing issues, please consider supporting the Earth Institute and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory today. You can also learn more on our Earth Day website.