Cycle for Science: Glacier Edition Completes Its Circuit

Wrapping up a week-long bicycle trip that has brought climate science to underprivileged schools.

By Elizabeth Hillary Case

This is the third of three blog posts documenting a bicycle trip through the Hudson Valley, led by Columbia University PhD student Elizabeth Hillary Case. Read the first one here, and the second here.

Bicycling perfectly balances the rate of human cognition and the pace of ecosystem change; cycling turns space into time. Riding north through the Hudson Valley, autumn announces itself mile-by-mile. The heavy scent of the city fades into the sweetness of overripe apples. Trees molt and change; colors wash the hillsides in waves as slow and fast as my pedal strokes. I watch sleek squirrels burying nuts at the base of oak trees on a quiet trail, and I dodge barreling semis on barely wide-enough roads. I’m wide awake, fully present. It’s the best way to pass the time.

Thursday and Friday — the last two days of my journey — I teach eight classes at two schools: a high school in Newburgh and an elementary school in Poughkeepsie. The Newburgh Free Academy starts at 7:10, when the sun has barely risen over the rolling hills. Heavy-lidded students make their way to their lab desks in the bright, decorated room of Joyce D’Imperio (“Ms. D”). They cheer at the “glacier goo.” The next class is a double period, so we have time to dig into the climate changes that Newburgh will face — a warming Hudson River, short-term drought, heatwaves. As always, students make pointed observations, finding the contradictions that make this global issue so difficult, and so pressing to tackle. They’re worried, but the problem feels so big they feel helpless. We pinpoint small steps they can take: meeting with city council members about climate change adaptation, learning about the local plants and animals, driving less, public action and resistance.

A few of them gather around after class and chat about cycling and safety, and whether it’s ethical to buy a new car. They want to act, but they also almost all have jobs outside of school. Where’s the time going to come from? Frankly, I don’t think they should have to take on this responsibility: we — I mean people like me: upper middle-class white adults — should have made moves a long time ago. Instead, we’ve hot-potatoed the problem to them, and the potato is getting hotter and it’s starting to burn.

Thursday afternoon is the best ride of the trip, through rolling apple orchards. It’s a hot day for mid-October, and the irony isn’t lost. I stop at Weed Farms for fresh apples, peach bread and a water refill. I amble and stop regularly; 20 miles takes me all afternoon. I finish the day with a ride over the Mid-Hudson bridge, just as the sun dips below the Catskills. Joseph Bertolozzi’s resonant, upbeat music, created from sounds made from the bridge itself and installed in its pylons, dances behind me over the water.

The last day of teaching is with 5th graders at Krieger Elementary in Poughkeepsie. I’m particularly excited to end my trip here — my grandfather grew up here, and his grandparents immigrated to Poughkeepsie from eastern Europe in the late 1800s, enticed by the resounding horns of steamships moving goods from the Atlantic inland to Albany. Poughkeepsie is where it is because of the Hudson River, and that’s part of the lesson I’m teaching. Glaciers, ice sheets, and water are integral to human history; as one student in Newburgh put it, learning science and history go hand-in-hand.

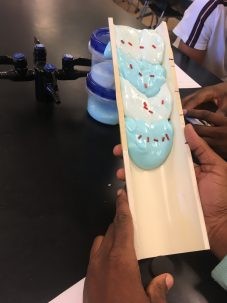

Fifth graders are by far my favorite age to teach: they’re still playful, exceedingly curious, and easy to engage with intellectually. More than one student connects the glacial erosion we talk about in class with the river erosion that created the Grand Canyon. The whole point of these lessons is to connect aspects of science — e.g. learning how to make observations and hypotheses — with creativity, relevance and joy. Goo allows for that exploration. Students squish it, tear it, break it, stretch it and learn to describe it. They relate goo, a hot commodity at most schools and the Pokémon cards of this generation, to science, and learn how glaciers move by setting up a mountain model with a halved PVC pipe, some goo and a few beads. A lot of them ask about the bike, sitting in the back of the classroom, and at the end of the day, teacher Skip Hoover asks them how many want to cycle across the country. More than half raise their hands! Let’s get these kids some bikes!

After the day ends, I pedal to the Jewish cemetery to look for my great grandparents’ grave. I think about the scale of life cycles: here I am, right where my family started 150 years ago. Here I am, where 20,000 years ago, an ice sheet bulldozed this valley. Here I am, where a hundred thousand years before that, it was ice free. Ebb and flow. Around and around we go. And yet we’ve likely interrupted that cycle by warming the planet, postponing the next ice age by 50,000 years. Humanity, and all our short-lived cycles, as a geologic force.

I can’t find my great grandparents’ graves, and I’ve got a train to catch. I ride the train home, face pressed to the glass as the Hudson speeds by. I pedal from 125th street in Harlem to Morningside Heights, to rest and shower and return to my daily cycle: wake up, study how glaciers form and move, repeat.