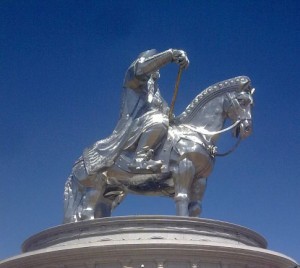

Chasing Ghengis Khan

Once you, as an outsider, spend considerable time in Mongolia, especially during Naadam and especially in the open Gobi steppe with people who still live as their ancestors did centuries ago, you will also begin to chase Chinggis Khaan.

People have been looking for 800 years. Looking for Chinggis Khaan, né Ghengis Khan. From the people searching for his birthplace to the people searching for his last resting place. After more than 800 years since his rise from the mountains of Mongolia, Chinggis lives on as a charismatic and almost mythical person. He seemingly rose from obscurity, quelled feuds between tribes, and created the largest land empire in world history. If you read beyond what you likely learned in high school or college, you will see his leadership skills were progressive and exceptional. You will learn that Chinggis has an influence on our world nearly 800 years after his death. From paper money to the pony express, from war strategy to the structure of the human genome, his life has touched generations of humans over the centuries.

When you begin working in Mongolia it is absolutely essential that you learn the importance of the man. Soviet communism attempted to quell his spirit and his importance in Mongolian culture. Mongolians were not allowed last names so everyone could be equal, so no one could trace their family history to the royal family. This, of course, did not work. In a culture that has songs and stories dating back centuries, if you, a native Mongolian, meet a stranger in the woods on the other side of the country and drink tea, break bread, and just lounge, you will soon break into a song that you and the stranger know from the depth of your soul. You will sing, smile, and enjoy a wonderful afternoon with this once distant, now close cousin. That kind of cultural bind does not break under any kind of political pressure. Perhaps it only made it stronger? See, in the late-1990s, soon after the fall of communism, Chinggis essentially rose from the ashes. He was everywhere in Mongolia – TV commercials for cell phones or a brand of vodka. And once you, as an outsider, spend considerable time in Mongolia, especially during Naadam and especially in the open Gobi steppe with people who still live as their ancestors did centuries ago, you understand the importance of the man and you will also begin to chase Chinggis. And, it is with this new project that our group of geographers, paleoclimatologists, ecologists, historians, and ecosystem modelers begin our pursuit of Chinggis Khaan.

Unlike other chasers who came before us, our search for Chinggis is not directly a pursuit of him as an individual. We understand he was an incredible leader who was the life force for the great Mongol Empire. Our pursuit is more contextual. We seek to understand the environmental conditions before, during, and after the rise of the Mongol Empire. In many ways, the success of the Mongol Empire is a historical enigma. At its peak during the 13th century, the empire controlled areas from the Hungarian grasslands to southern Asia and Persia. Powered by domesticated livestock, the Mongol Empire grew at the expense of farmers in Eastern Europe, Persia, and China. Two commonly asked questions of this empire are “What environmental factors contributed to the rise of the Mongols?, and “What factors influenced the disintegration of the empire by 1300 CE? . For a long time (centuries?), it was thought that drought partly drove the Mongols on their conquest in Eurasia. Luckily enough for us, a serendipitous collection of a few pieces of deadwood and old Siberian pine trees suggests essentially the opposite. Our collection of an annual record of drought, currently dating to the mid-600s CE, suggests that the early-1200s were unusually wet. Of course, these findings are very, very, very preliminary – we only have two trees through this time period.

So, with funding from the Lamont Climate Center, National Geographic Society, West Virginia University, and the Dynamics of Coupled Natural and Human Systems program of the National Science Foundation, we are headed back to Mongolia for a fourth straight year to scour the study site that yielded a 1,300-year record for more old, dead wood. With a combined crew from the National University of Mongolia, West Virginia University, and the Tree Ring Laboratory of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University and the Earth Institute, we will spend 10 days in the field seeking, documenting and collecting wooden gold, xylemite if you will.

Part of our crew will also spend about three days at upper tree line on a mountain in the western Khangai Uul (uul is Mongolian for mountain) updating and expanding the collection that suggested that it was warmer during the rise of the Mongol Empire. We are so excited. We have a great crew, will be spending our time mostly in one place, and will have some of the finest scenery in Mongolia in our eyes everyday.

Frankly, we are also excited about our larger project. We honestly do not know what the end results will be. The idea that wet conditions aided the expansion of the Mongol Empire is simply a hypothesis built upon ecosystem ecology, human ecology, and our preliminary results. See, energy is critical for human and natural systems to function, yet few studies have examined the role of energy in the success and failure of past societies. Increased rainfall on the Great Gobi Steppe should allow the grassland to capture more solar energy. Greater grass production logically would have allowed the Mongol Empire to capture, transform and allocate this energy through their sheep, horses, yak, etc. In turn, this should have allowed greater energy from which Chinggis could develop a larger and more complex social, economic and political system.

Feeding tree-ring based climate history into an ecological model, we plan to investigate how past climate influenced grassland productivity, herbivores and, thus, energy flow through the Mongol ecosystem. These data will be compared to historical records on the empire and sediment records from lakes that can estimate herbivore density.

Much has been made about the demise of cultures as a result of a downturn in climate or degradation of their environment. Our estimates of energy availability and environmental quality allows us to investigate whether the contraction of the empire was related to drought, cold, declining grassland productivity, or poor water quality associated with rapid urbanization and climate change.Thus, as part of our larger project, we will test the hypothesis that the arc of the Mongol Empire was influenced by the energy available to nomadic pastoralists for building a mobile military and governmental force sufficient to conquer and govern a significant portion of Asia and Eastern Europe.

We leave in less than two weeks. As happens each year around this time, memories of past trips are revived and we begin seeping back into the Monglish culture that develops on these trips. We look forward to re-uniting with colleagues like Baatarbileg Nachin and his students like Bayaraa. A highlight this year will be working alongside a Mongolian postdoc, Sanaa, who Neil met as an undergrad in 1998. It will be an honor and pleasure to work with Sanaa again. Mongol phrases and words are bubbling up from the depths of our gray matter. Mongolian music is spinning nearly full-time in one household; a soundtrack for this year’s fieldwork is coming into shape.

We hope to catch a set of Altan Urag, a rising rock band in Mongolia. To us, they represent some of the cultural struggle in Mongolia today: “How do we maintain the qualities we are so proud of during the height of our empire, as new or external culture moves into our land?” and “As commercialization in the post-communism era (including a ‘gold-rush’ in the mining industry that created one of the fastest growing economies in the world) pushes and pulls us, how do we maintain who we are?” Altan Urag and young Mongolian artists are reaching back in their history for symbols and sounds that make them distinctly Mongolian. At the same time, these artists keep their eyes and ears open to the new possibilities of their larger world. Similar to how Chinggis melded European and Chinese technology to forge his great empire, many of today’s young Mongolians blend their history with external elements to create a new Mongolia. We cheer these efforts on. We are big fans.

Follow the rest of the posts at Mongolian Climate, Ecology & Culture