8 Surprising Facts About Marie Tharp, Mapmaker Extraordinaire

Maybe you already know that she created some of the first maps of the ocean floor and helped discover plate tectonics. Here are some lesser-known facts about this history-making cartographer.

July 30 marks 100 years since the birth of Marie Tharp, a pioneering geologist and cartographer who created some of the world’s first maps of the ocean floor. We’ve been celebrating her achievements and legacy with blog posts, webinars, giveaways, and more. Follow along here and here.

Tharp began working at the Lamont Geological Observatory (now the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University) in 1949, a time when women weren’t always welcome in the world of science. Despite these extra obstacles, she went on to discover the mid-ocean ridges and helped to prove that the Earth is made of plates that glide over a viscous mantle. Tharp passed away in 2006, but her work has forever changed the fields of geology and ocean exploration.

Below, read some of the lesser-known facts about this history-making cartographer.

1. Mapmaking was in her blood.

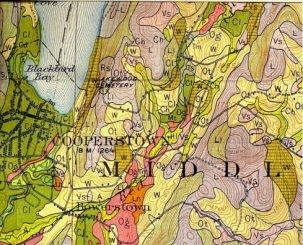

Marie Tharp’s father, William Edgar Tharp, was a soil surveyor with the USDA. He mapped soils in 14 states — from New York to Florida, and west to Idaho — and young Marie loved to go with him in his fieldwork. The Geological Society of America notes, “As a small child, she would sit in the back of her father’s truck ‘making mudpies and generally being a nuisance.’” These trips likely sparked her interest in science.

The fieldwork may have helped in other ways, too. “One cannot help but to speculate that Marie Tharp’s childhood exposure to her father’s mapping activities helped to develop her own sense of spatial thinking,” writes Edward Landa from the U.S. Geological Survey. In addition, he points out that, “A home where education was a priority, and a father whose profession provided a role model in science in general, and mapmaking in particular, were likely strong influences in Marie’s life. Indeed, mentorship and a broadly inclusive environment are now recognized as key components of programs to promote diversity in the workforce.”

Marie herself once said, “I guess I had map-making in my blood, though I hadn’t planned to follow in my father’s footsteps.”

2. She probably wouldn’t have been able to study geology if it hadn’t been for World War II.

When Tharp first went to college, there weren’t many opportunities for women except as teachers, secretaries, or nurses. None of these appealed to her, so she majored in English and music.

“I never would have gotten the chance to study geology if it hadn’t been for Pearl Harbor,” Tharp once said. “Girls were needed to fill the jobs left open because the guys were off fighting. A year after the war started, the geology department at the University of Michigan opened its doors to women. In 1943, about ten of us girls responded to one of their fliers, which promised a job in the petroleum industry if we got a degree in geology.”

After graduating with a master’s degree in geology, Tharp went to work with Stanolind Oil and Gas Company in Tulsa, Oklahoma. According to Gary North from the U.S. Geological Survey, the company wasn’t sure what to do with a woman geologist since she couldn’t go out into the field with the men, so Tharp was stuck doing office work — transferring data from well logs and drafting. Bored with her work, she spent her free time earning a bachelor’s degree in mathematics.

Searching for something more challenging, she went to work at the Lamont Geological Observatory in 1948. She must have found the work stimulating, because she remained at Lamont until she retired in 1983.

3. When she found evidence that the continents move, her colleague dismissed it as “girl talk.”

In 1952, as Tharp was aligning six sounding profiles running across the Atlantic, she noticed that all of profiles showed a V-shaped notch at the center of the mid-ocean ridge. “The individual mountains didn’t match up, but the cleft did, especially in the three northernmost profiles,” Tharp explained. She thought the notch must be a rift valley — a place where the seafloor was spreading apart, with new from below material welling up around the fault and building the mid-ocean ridge.

“When I showed what I found to Bruce [Heezen], he groaned and said, ‘It cannot be. It looks too much like continental drift,’” said Tharp. “At the time, believing in the theory of continental drift was almost a form of scientific heresy. Almost everyone in the United States thought continental drift was impossible. Bruce initially dismissed my interpretation of the profiles as ‘girl talk.’”

It took half a year until Heezen was convinced, and another three years after that until the findings were published as an abstract — without crediting Tharp.

4. Jacques Cousteau accidentally helped to prove her right.

The famous ocean explorer Jacques Cousteau didn’t believe the rift valley really existed. So he set sail into the Atlantic with an underwater camera rig, intending to prove Tharp and Heezen wrong. In his photos and videos, displayed to a large crowd at the First International Oceanographic Congress in 1959, “the great black cliffs of the rift valley, sprinkled with white glob ooze, loomed up through the blue-green water,” Tharp wrote in a piece called ‘Mappers of the Deep.’ One image depicted “pillows of lava newly extruded from the center of the earth.”

These images provided the world’s first real look at the rift valley, and helped to convince other skeptics that it really existed.

5. She wasn’t allowed to go on research cruises for the first 20 years of her career.

When Tharp began her career at Lamont, it was still considered “bad luck” to have a woman onboard a ship. Thus, it was Heezen who went out on the research cruises that collected the ocean depth data, while Tharp remained in the office, translating the data into maps. She didn’t set foot on a research cruise until 1968.

6. She may have had a bit of a temper.

Although required to behave meekly in a male-dominated field, her passion for her work sometimes caused flare-ups. Lamont special research scientist Bill Ryan remembers walking in on Marie Tharp screaming at Heezen because she had just discovered that his ‘intuition’ had caused her to waste weeks of painstaking work. “She tore up this huge sheet she’d been working on for a month or so,” says Ryan.

Similarly, when Tharp and Heezen argued about whether or not the mid-ocean rift might be evidence of seafloor spreading, she reportedly threw erasers and ink bottles at him.

Despite the occasional screaming matches, Tharp and Heezen were a good team, and she remained devoted to him. According to Ryan, after Heezen’s unexpected death in 1977, Tharp wasn’t able to produce anything new anymore — she’d lost her intellectual partner. In 1997, when her maps were displayed in the Library of Congress alongside historical documents of great importance, she cried and said, “I wish that Papa and Bruce could see it.”

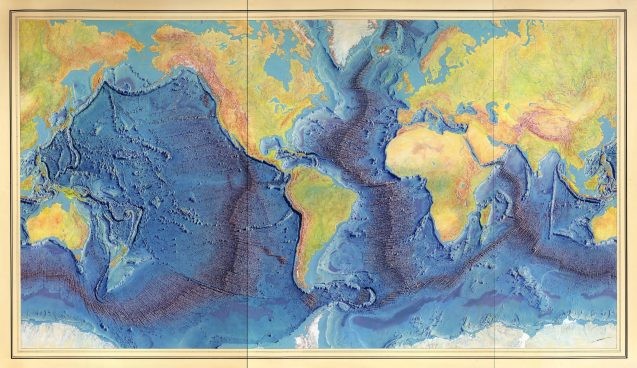

7. Her map of the world oceans was so large that only one printer in the country could handle the job.

Tharp and Heezen’s famous 1977 map of the world ocean seafloor measured about 6 feet by 3.5. Only one printer in the country, located in Minnesota, was large enough to handle the job, says Ryan. It cost $40,000 to print the map — equivalent to about $170,000 today. Tharp wasn’t happy with the quality of the first print, so she made them run it again, at great expense.

According to Ryan, Heezen had first found out the printer’s maximum size capacity, then asked the artist Heinrich Berann to paint the map to those specifications. Berann was famous for his landscapes, but had been working with Tharp and Heezen for years, painting the maps that Tharp sketched.

8. She relied on instinct for a lot of her mapmaking, yet her maps are remarkably accurate.

To make her historic maps, Tharp relied on depth data collected by research cruises. But since the ship couldn’t cover every inch of the oceans, it was up to Tharp to fill in the blanks in between those lines, to try to understand how all the pieces fit together. For this, she had to rely on her intuition and knowledge of geology — to the point that that Heezen once wrote that “what people think the bottom of the ocean looks like, that is, what most scientists and informed laymen think it looks like, is what Marie Tharp thinks it looks like.”

Fortunately, she turned out to be right — her maps are surprisingly accurate. This is all the more remarkable since, as Landa writes, “neither she nor anyone else knew any details about the tectonic and volcanic processes that form the seafloor geomorphology; yet her maps in areas of sparse data (the Southern Oceans, for example) are far better than would have been possible by interpolating from data alone.”

In the later decades of her life, Tharp’s talents, achievements and legacy finally began to receive the recognition they deserved. She won numerous awards, and in 1997, the Library of Congress named her as one of the four greatest cartographers of the 20th century.

Join in the #MarieTharp100 celebrations on Twitter and Instagram.