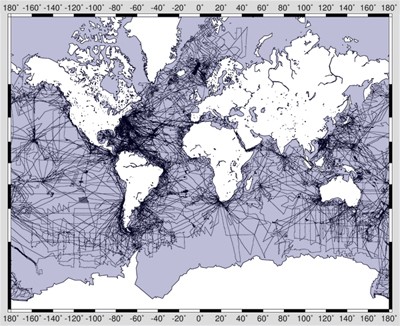

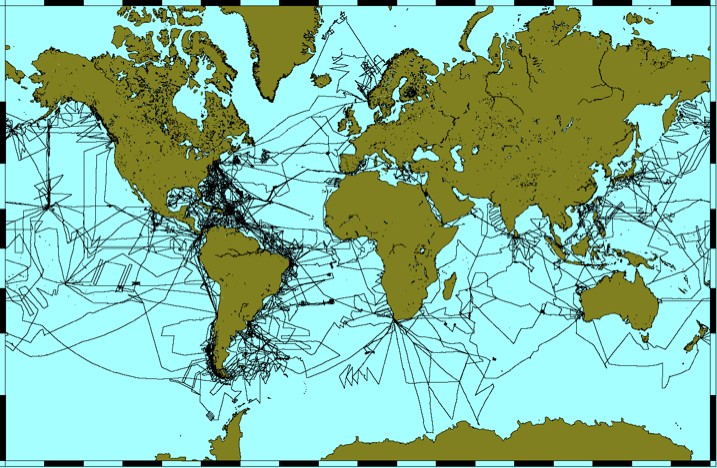

Science survey tracks of all research ships operated by Lamont: Vema, Eltanin, Conrad, and Ewing, totaling an estimated 3,345,000 nautical miles. Credit: John Diebold & GMT mapping software

Since 1953, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory has operated distinguished research vessels that collectively have enabled pioneering explorations of our planet's oceans and seafloor.

Lamont-Doherty currently owns and operates the R/V Marcus G. Langseth, which serves as the national seismic research facility for the United States academic research community.

Looking back, LDEO has operated four distinguished research vessels–the Vema, the Conrad, the Eltanin, and the Maurice Ewing–which collectively have enabled the Observatory to conduct explorations of our planet’s oceans and seafloor for decades.

Today’s methods of marine geophysical research are evolving faster every year. Indeed, it was in the process of planning for the Ewing’s midlife refit that the scientific community came to the conclusion that, even with such a refit, she would not be able to provide the advanced tools that are required to conduct such research into the future. Thus the decision was made to acquire a new seismic vessel that would be better suited to these new scientific requirements. And, in Western Legend, a commercial seismic exploration vessel owned by Western Geco, Inc., the ideal candidate was found.

The National Science Foundation provided funding of more than $20 million to support the purchase and refit of the Western Legend, which after a year-long outfitting with modern laboratories and scientific equipment, became in 2006 the most capable academic research vessel utilizing acoustic and seismic technologies in the world, with new laboratory spaces and deck space configurations optimized for ocean-bottom seismometer operations or general oceanography.

The vessel, renamed the Marcus G. Langseth in honor of the late Lamont scientist, can tow four 6-kilometer-long streamers. It is equipped to carry out two- and three-dimensional imaging of the ocean floor and the Earth’s deep interior. These seismic cross-sections, like medicine’s CAT scans and sonograms, enable us to peer directly into the Earth. Even better, because the receiving systems used by the vessel to record the sounds that probe the Earth’s interior were substantially more sophisticated than those found onboard the Ewing, the Langseth’s greatly improved imaging capabilities did not come at a cost of increased sound levels transmitted into the ocean, thus minimizing possible impacts upon marine life.

G. Michael Purdy, Past Director of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, summed it up best when he said, simply, “The purchase of this new ship is the beginning of a new era in Lamont ship operations.”

The Langseth has allowed us to learn more about seafloor spreading, earthquakes, magma flow, gas hydrate deposits, continental drift, and more, expanding scientific knowledge about the Earth and contributing to our ability as humans to withstand its extreme forces.

R/V Vema approaches the Piermont Pier, circa 1960.

Built in 1923 for E. F. Hutton and christened Hussar—a 202-foot, three-masted, luxuriously appointed schooner with teak decks, Louis XV bedroom, marble-rimmed fireplace, Oriental rugs, stained-glass windows and gold-fauceted bathrooms—the iron-hull racing yacht was sold 11 years later to Georg Ungar Vetlesen, who renamed her Vema, for his wife, Maude (née Monell).

Like all oceangoing yachts in the United States, the Vema passed to government ownership during World War II, and was first put to use patrolling coastal waters for the Coast Guard. Later she underwent a drastic conversion to a floating barracks and training ship for the U.S. merchant marine, losing her gold faucets and other amenities. After the war, she lay abandoned and aground off Staten Island for several years, until being salvaged by a Nova Scotian captain for use as a charter vessel.

It was in this guise that she was leased (and soon purchased, for $100,000) by Lamont in 1953. Almost immediately Vema started circling the globe, 320 days a year, embarking on nearly boundless missions to explore every ocean—and eventually becoming the first ship to sail a million nautical miles making scientific observations.

The Vema collected much of the bathymetry and paleomagnetic data that was pivotal

to the early proof of seafloor spreading, and was also the first ship to perform continuous reflection seismic profiling with a Lamont-designed system. Along with her companion, the Conrad, she had standing orders to stop once or twice every day to collect a wide range of samples from wherever she happened to be. To do that, crews learned how to lower two instrument-laden wires simultaneously from rolling ships to the seafloor. The instruments sampled seawater, detected currents, photographed the bottom, measured seafloor heat flow and, of course, collected sediment cores. Lamont’s founder (and the driving force behind the acquisition of the Vema) Maurice “Doc” Ewing famously laid down the dictum “a core a day.” In 1948, only about 100 deep-sea cores existed. By 1956, thanks to the Vema, Lamont had collected 1,195. (Today our core lab holds nearly 19,000—a library of the seafloor available to the entire scientific community.)

The work wasn’t without danger. In 1954, while trying to secure fuel drums that had broken free on deck in a massive storm off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, Ewing, his brother John, First Mate Charles Wilkie, and Second Mate Mike Brown were swept overboard by a huge wave. Somehow, despite the heavy seas, the captain was able to turn the ship around and rescue the two Ewings and Brown. Tragically, Charles Wilkie was not found. Ewing, who had taken a paralyzing blow to the neck in the accident, would walk with a limp from that point on.

The Vema sported a huge, determined-looking eagle figurehead, well representing Lamont’s indomitable spirit. (Today it hangs in the front hall of Lamont’s Geoscience Building.) By the time she was retired, in March 1981, this now-legendary research vessel had collected vital data along 1,225,000 nautical miles of track—a world record.

Renamed Mandalay and refitted as a luxury cruise ship, she was at last report placidly cruising the Caribbean.

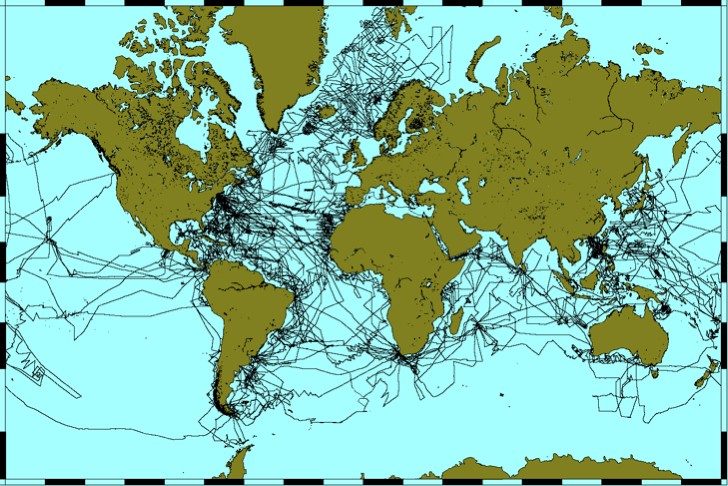

R/V Vema science tracks, totaling an estimated 1,225,000 nautical miles. Credit: John Diebold & GMT mapping software

R/V Conrad, 1980. Credit: Henry Chezar

Just like her illustrious big sister, Lamont’s second ship, the Robert D. Conrad, a new research vessel built by the Navy and given to the Observatory to operate in 1962, embarked on ambitious, near-continuous research missions from the very start. (She would eventually follow Vema as only the second ship in history to log more than one million nautical miles of oceanographic research.)

Using deep-sea seismic reflection equipment developed at Lamont, both research vessels conducted a worldwide mapping of the sediments accumulated on the ocean floors, while at the same time collecting magnetic, gravity and heat-flow data. This vast flow of information contributed enormously to our present understanding of oceans as youthful features, originating at the mid-ocean ridges by a process of intrusion of mantle rocks, followed by lateral displacement of the cooled crust—a process known as seafloor spreading.

In addition to its manifold oceanographic, biological, geochemical, geological and geophysical work, the Conrad was notable in that she was equipped, starting in 1974, with tools for multichannel seismic (MCS) surveying. Starting with four airguns and a 2,400-meter-long, 24-channel hydrophone array, the equipment was over time systematically upgraded and improved: by the time she was returned to the Navy, in 1989, the Conrad ’'s MCS equipment consisted of ten airguns and a 4,000-meter-long, 160-channel hydrophone array. Over her 27 years of service to the Observatory, the Robert D. Conrad acquired 850 seismic profiles over the course of 35 different surveys.

R/V Conrad science tracks from 1962 to 1989, totaling an estimated 1,100,000 nautical miles. Credit: John Diebold & GMT mapping software

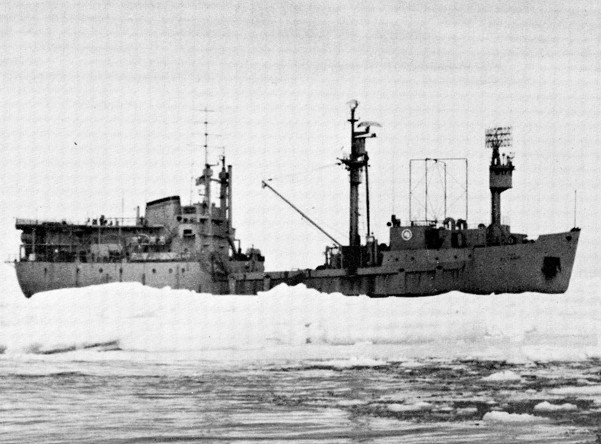

With a bridge low in the after part of the ship, the R/V Eltanin's enclosed ice tower was often used for spotting icebergs. Credit: National Science Foundation

The USNS Eltanin was launched in 1957 as a noncommissioned Navy cargo ship with a special feature that would prove essential to scientists: she was built with an ice-capable, double hull, and officially classified as an Ice-Breaking Cargo Ship. In August of 1962, she was refitted to perform research in the Southern Ocean and reclassified an Oceanographic Research Vessel (T-AGOR-8)—in fact, Eltanin was one of the world’s first Antarctic research ships.

Lamont Geological Observatory (as it was known at the time) was selected to install, and initially to maintain equipment for underway geophysical measurements, including precision depth sounding, gravity, magnetics, and seismic reflection profiling. But Eltanin’s missions were not limited to geophysical work: physical, biological and geological groups, several from Lamont, participated in many of her cruises, occupying more than 1,500 “hydro stations” and making vertical profiles of temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen and other parameters. The oceanographers also made thousands of bathythermograph casts, took numerous bottom photographs and made measurements of light scattering and ocean currents.

(All of this work was supported by the National Science Foundation's Division of Polar Programs.) In the period between 1962 and 1975, scientists and technicians aboard Eltanin logged and archived data along 420,000 nautical miles of track, extending from the Atlantic westward into the central Indian Ocean, between 40° and Antarctica.

In 1975, Eltanin was transferred to the Argentine Navy and renamed Islas Orcadas. She would continue to cruise the South Atlantic sector for several years, often with Lamont science projects aboard.

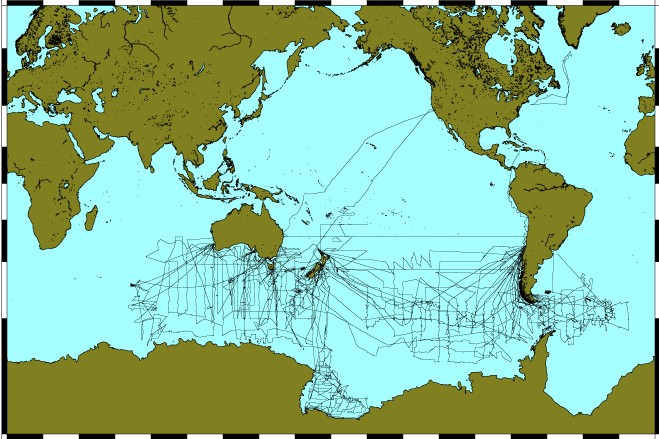

R/V Eltanin science tracks from 1962 to 1975, totaling an estimated 420,000 nautical miles. Credit: John Diebold & GMT mapping software

R/V Ewing from the air, during early shakedown legs, May 1990. Credit: Michael Rawson

The Ewing began her existence as M/V Bernier, a 230-ft, 1,976-gross-ton multichannel seismic survey ship built in 1983 for Petro Canada. The downturn in the oil industry during the late 1980s led her owners to put the Bernier up for sale. Late in 1988, Columbia University purchased her for about $6 million. Another $5 to $6 million was required to refit the ship as a general-purpose research vessel. The refit was completed in June 1990, with funding from the National Science Foundation, to whom title was passed in 1995.

In her nearly fifteen years of service to scientific exploration, the Maurice Ewing accumulated well over half a million miles of track, including over 20,000 nautical miles of multichannel seismic (or MCS) profiles. With her cruising speed of 11 knots and an endurance of up to 60 days, the Ewing was able to ply the seas from Atlantic to Pacific, and from the Arctic to Antarctica, calling in ports as dispersed as Broom, Australia; Anglamassck, Greenland; Capetown, South Africa; and Dutch Harbor, Alaska. These long, richly rewarding scientific trips were not uneventful in other ways, either: in August 2001, while cruising off the northern coast of Somalia, the Ewing was attacked by armed pirates who pursued her firing AK-47 rounds and even a rocket-propelled grenade (fortunately, the latter glanced off the ship without detonating). The ship managed to outrun the pirates with no significant physical damage done.

Truly a multipurpose ship, the Ewing was unique in the U.S. academic fleet in her capability to collect high-quality MCS data. Her set of equipment included a 20-element seismic source array, a 6-kilometer-long hydrophone streamer cable featuring 480 channels, and a portable high-resolution system with 2 GI (generator injector) sound sources. “Doc” Ewing would have been proud indeed: the ship that carried his name was, in its time, the most capable seismic research vessel in the world.

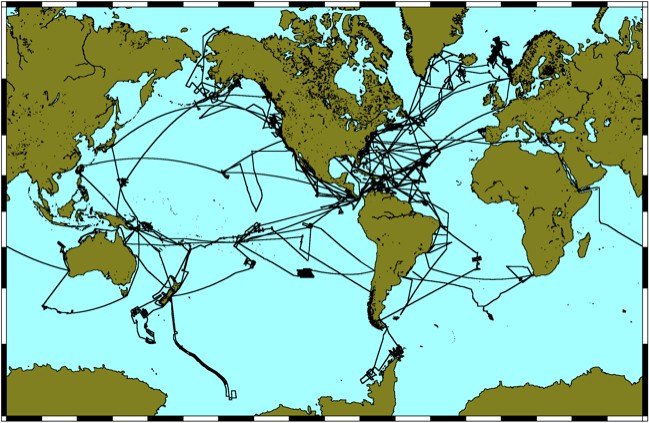

R/V Ewing science tracks from 1988 to 2005, totaling an estimated 600,000 nautical miles. Credit: John Diebold & GMT mapping software