The Virus and the Cyclone: The Tragedy in India and Bangladesh is Double

More than four million people have been forced to abandon their homes and reach emergency shelters, increasing the risk of contagion.

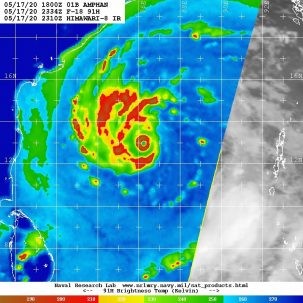

While the number of infections and deaths related to COVID-19 in the U.S. continues to decrease, the opposite is true in many other countries. Among these are India and Bangladesh, where another disaster added to the tremendous tragedy of the pandemic last week: the arrival of supercyclone Amphan, the strongest storm ever recorded in the Gulf of Bengal, with winds reaching speeds of up to 160 miles per hour.

More than four million people in India and Bangladesh were forced to flee their homes and reach emergency shelters, effectively increasing the risk of contagion.

Thirteen billion in damages

Amphan hit the ground on the afternoon of May 20 on the border of India and Bangladesh, near the city of Calcutta, causing more than 100 victims and creating damages estimated to cost more than $13 billion in West Bengal alone. The storm comes as India and Bangladesh struggle to control coronavirus outbreaks. India has exceeded 120,000 infections, adding more than 6,000 new cases per day, with this number growing continuously. “It is the first time that we are dealing with two disasters: COVID-19 and a super cyclone,” said Satya Narayan Pradhan, director general of the National Disaster Relief Force.

“Rescuers must wear masks, everyone must wear a visor, gloves … It is almost certain that they will have to access areas of high contagion and deal with infected people. It’s a double challenge,” he continued.

Addressing the pandemic and cyclone disasters at the same time truly is a challenge for the two governments. In the state of West Bengal, for example, there is normally space in the shelters for 500,000 people but, due to the current rules of social distancing, this number has been reduced by more than half to just 200,000 people. In addition, many found themselves forced to walk to emergency shelters, given the reduction and dangers associated with public services.

Cyclone Amphan also brought heavy rain to the world’s largest refugee camp at Cox’s Bazar, where nearly 1 million Rohingya refugees have fled violence in the state of Rakhine in Myanmar, and where the first known cases of COVID-19 were confirmed at end of March. Fortunately, the camp seems to have suffered no casualties from the cyclone, although the situation has increased the risk of contagion in the field.

Further evidence of a changing climate

The fact that Amphan developed from a Category 1 storm to a Category 5 monster in just 24 hours can be associated with climate change. Recall that it is the combination of several factors such as sea level rise, the intensification of storms and rains together with social and infrastructural factors that increases risks exponentially. Their combination as a “team” does the greatest damage.

This is a present reality, not a future forecast. Suffice it to say that the estimates for the end of the century foresee a global sea level rise of the order of about 3 feet — and this value is probably underestimated. In the case of Amphan, storm surges brought waves up to nearly 10 feet high.

The tragedy of the supercyclone has added to that of the pandemic. Among the victims of the supercyclone it will also be necessary to count those who have been exposed to COVID-19 during the evacuation and while giving relief. This is another way in which the virus continues to creep into the folds of our lives, adding to the potential effects of climate change.

COVID-19 is far from defeated. It can attack and weaken our society in many ways, and we must not let our guard down.

Adapted and translated from an article that was originally published in La Repubblica.

Marco Tedesco is a research professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.