For all of its violent destruction, the earthquake that struck Haiti on Jan. 12, 2010, hardly scratched the surface of the island. But scientists now say they have found some of the best clues to understanding the quake under water.

The deadly quake also shook loose an enormous amount of sediment, sending large volumes of earth sliding into the sea from the shore and also downslope from shallower to deeper portions of the Canal de Sud, adjacent to the southern prong of the island of Hispaniola. That caused water to slosh back and forth in the basin, like in a bathtub, and generated a small tsunami that killed several people.

The toll was miniscule compared to the hundreds of thousands believed to have been killed in and around Port-au-Prince. But the landslides bore important fruit for a team of scientists from Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and other institutions, including Queens College of the City University of New York, who came to study this part of the region immediately after the earthquake.

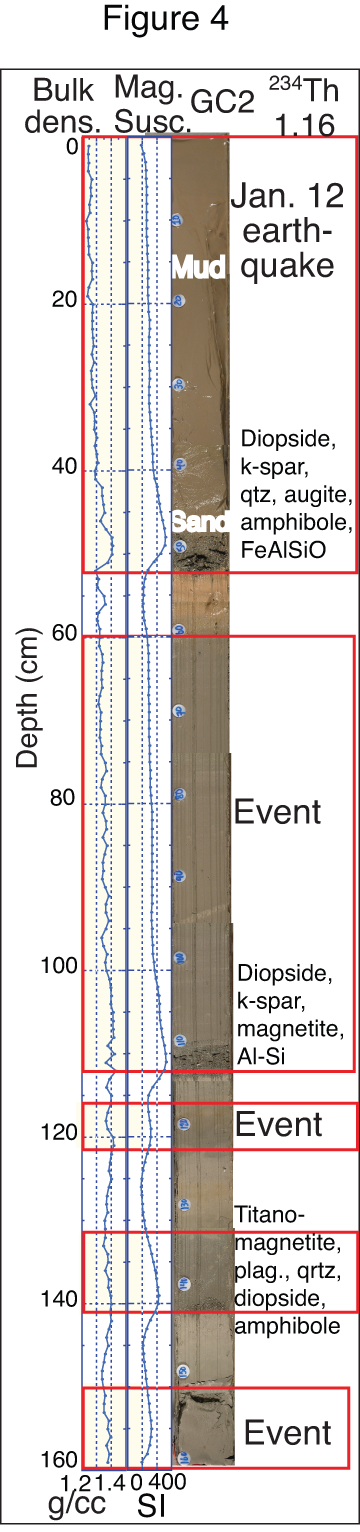

Within weeks of the disaster they were out on a research vessel studying the water column and drilling out long cylinders of mud and sand from deep in the Canal de Sud. They found that as some of the sediment unleashed in the landslides settled, it left patterns that reflected the water sloshing back and forth in the Canal de Sud. They were able to identify similar imprints further down in the sediment that were likely caused by landslides triggered by several previous quakes.

Their work, described in a paper published in the journal Geology, gives scientists another way to decode the seismic history of this and other regions, and to better assess the risks posed by future earthquakes.

“The important thing is, if you have an earthquake, you should also look for layers of mud and shaking, to help map out the paleoseismology,” said lead author Cecilia McHugh, a Lamont researcher and Queens College faculty member.

Haiti is crossed by the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden fault, a “strike slip” fault where huge slabs of earth grind past each other far below the surface. The January earthquake included additional thrusting motion, but that deep rupturing did not reach the surface, making it more difficult to study. The methods used in Haiti could help decipher what’s going on in other areas where such activity may occur, such as the San Andreas fault in California, another “strike slip” fault which has had similar earthquakes that did not break the surface.

McHugh said the research in Haiti, and in other earthquake hot spots such as the Sea of Marmara in Turkey, aims to figure out where and when earthquakes happened. They can use that history to calculate the sequence and timing of earthquakes in a particular segment of the fault zone so people can be better prepared if there’s one due. “As a geologist, that’s all I can do,” she said.

Geologists can provide input to civic authorities so they can be prepared through better construction, reinforcement of roads, hospitals and schools, and better public education about earthquake hazards, she said.