Trials & Tribulations of Coring the Agulhas Plateau

Trying to drill sediment cores while the ship rides large ocean swells off the coast of Africa isn’t easy, but it’s paying off for science, writes Sidney Hemming.

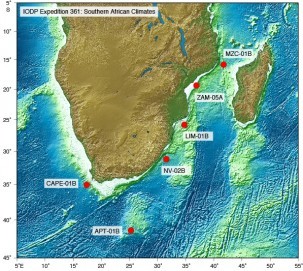

Read Sidney Hemming’s first post to learn more about the goals of her two-month research cruise off southern Africa and its focus on the Agulhas Current and collecting climate records for the past 5 million years.

A lot has happened since my last post. As we were heading south to the Agulhas Plateau, one of the scientists had to be evacuated by helicopter for medical treatment. We were within a day of the Agulhas Plateau site and had to go back to near Port Elizabeth for the handoff and then return to drill the plateau. The weather at the plateau was bad enough that we were probably going to have a delay anyway, so we didn’t lose too much time. Our colleague is fine now, and our drilling on the Agulhas Plateau has been a success.

We have had some trials and tribulations because of the large ocean swells and because the sediments do not have as strong of a physical property signal as the previous site. Both of these factors increased the challenge for the stratigraphic correlators, so it has been a real cliff-hanger to find out if we can splice together a continuous section. Because of the small signal-to-noise of the physical properties, the scanning took longer and the records for correlating are not quite as clear. This has created a backup in the work flow, and it means the descriptions and scanning (and some sampling) of the split cores will be continuing as we begin our transit. And it means that until all this is completed we will not know for sure how continuous of a record we have. We are reasonably sure we will have few or no gaps in the splice, but it will be nice to see it all completed.

Meanwhile, we came here thinking that we would get a high accumulation rate record for the last million years, but the accumulation rates are modest between the surface and about 100 meters—approximately 2 cm per thousand years. Below that, they turned out to be really quite nice, approaching 7 cm per thousand years through much of the Pliocene. The low accumulation in the Pleistocene is a disappointment as there is a great interest in the mid-Pleistocene climate transition, but it does look like it is a continuous record. The higher accumulation in the older sediment is exciting because the early Pliocene is a warm time in Earth’s history and the most recent with global temperatures as warm as modern times. So we Earth scientists are quite eager to understand everything we can about this interval. The Agulhas Plateau site, near where the Agulhas Current swings back toward the east, is well situated to provide some important information about linkages of different factors in the climate system.

Again at this site, as with the previous site, the development of the time scale has been fun and exciting to watch. We have four groups of organisms that are aiding in our time scale—in addition to foraminifera and nannofossils, there are abundant diatoms and dinoflagellates here. This is great for the biostratigraphy and also great for our participants whose post cruise research will use diatoms for documenting paleo-environmental changes. The magnetic stratigraphy started out looking bleak because the weak signal was messed up by the coring process in the first hole, due to the ship’s heave in the waves. They almost gave up, but the second core preserved a great record. So we are going to have an excellent time scale for this site as well.

Meanwhile the saga continues in our quest to get permission from Mozambique to drill in their waters. We have word from our contact in the American embassy that the form has been signed by the Foreign Ministry and is now with the ministry that deals with fisheries. While that process continues, we have to start toward our next site. Our decision is to head toward the Zambezi site, as it is going to take us six days to get there anyway. If we don’t get permission before we arrive, we’ll have to turn around and head for the Cape site.

The Zambezi and Limpopo sites are near major rivers. We hope they will give us a record of the terrestrial climate variability in southeastern Africa through the last 5 million years that can be compared with the Agulhas Current and other oceanographic factors. The hope is that we will get a continuous record with a variety of proxy data for factors such as precipitation, runoff, distribution of vegetation on the landscape, and surface ocean temperatures. The coring is going to be fast at these sites because they are much shallower. In the happy case that we get to drill there, we will then have another long transit to finish off the analyses.

Sidney Hemming is a geochemist and professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. She uses the records in sediments and sedimentary rocks to document aspects of Earth’s history.