Time and Technology and the Really Down Deep

Two years before Google Earth was launched, Bill Ryan and Suzanne Carbotte, oceanographers at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, began a project to transform the way we look at the ocean. They started collecting reams of data that had been gathered by scientists sailing on research vessels all over the world since the 1980s, one ship transect at a time.

Two years before Google Earth was launched, Bill Ryan and Suzanne Carbotte, oceanographers at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, began a project to transform the way we look at the ocean. They started collecting reams of data that had been gathered by scientists sailing on research vessels all over the world since the 1980s, one ship transect at a time.

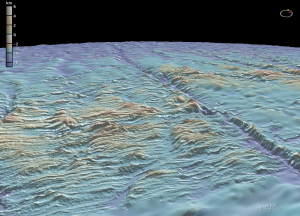

Through this nine-year labor, built atop decades of scientific research, the two have built a remarkable thing for all of us to see: The real deal, under the sea — volcanoes, mountain ranges, gaping canyons, sharp-edged faults, the ripples of abyssal hills. At some point, Google Earth came to them and said, “Whatcha got there?”

And now, we can tour it all on Google Earth, appropriately enough in this World Oceans Month. (June 8 was the official World Oceans Day, but it takes at least a month to fit in all the things we could say about oceans, how important they are to our survival, and how messed up they have become – more on that below).

This being a Google Earth thing, we not only can view the landscape from above – we can dive under the sea surface to gawk at volcanic seamounts, the vast mid-Atlantic Ridge, troughs larger than the Grand Canyon trailing off the continental shelf, long cracks where plates of the earth’s crust grind together, filled with the threat of earthquakes and consequent tsunamis. At this site sits a virtual tour of seafloor wonders; at this site, a second tour of the surreal world of hydrothermal vents.

The snappy world of Google Earth’s cool, fast-moving planet belies the hard and slow effort needed to build the underlying science, the hard facts that make up the reality in the virtual world. The real numbers:

- Two decades of multi-beam sonar measurements

- Hundreds of scientific cruises

- Roughly 3 million miles traveled

- Just under 5 percent of the oceans covered (doesn’t seem like a lot, but it covers an area larger than North America)

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-_4NkUpot_s&feature=player_embedded[/youtube]

We can fly over and photograph and take radar readings of the earth’s surface (and the moon and Mars, for that matter) that give fine detail. But shooting sonar and creating topographical renditions through miles of ocean water is another matter. The new ocean images created by Ryan and Carbotte resolve to 100 meters.

Carbotte says that to map the full ocean floor at a comparable resolution would take the equivalent of a ship going out and mapping continuously for 200 years.

While we’re in World Oceans Month, other facts regarding the sea come to mind. Half the earth’s population lives on the coasts, many of them vulnerable to the effects of tsunamis, as was shockingly demonstrated in Japan last March. An equal share of the world’s people relies on oceans as a primary source of protein. The oceans regulate climate, which is changing. The rising level of CO2 in the atmosphere is ultimately making the oceans more acidic, and less friendly to life as we know it. Sea level rise from global warming will have a major impact in the coming century.

The impacts will hit many of the poor disproportionately, but the well-off will feel it as well, whether it’s a vacation home washing away in a higher storm surge, or the political and economic effects of massive displacement of populations. At a conference at Columbia Law School earlier this spring, participants focused on what happens to people whose homelands wind up under water.

In a blog on Huffington Post, Michael B. Gerrard of the Center for Climate Change Law at the law school talks about some of the legal implications, and notes, “As a civilization our laws are often based on the assumption of a static world. This norm is now being challenged, as global climate change shifts natural boundaries.”

So, too, when we dive into the deep blue sea and encounter volcanoes, earthquake zones and a new and unexpected landscape, we can see the natural boundaries of our world change before our eyes.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d0td79QuxpA&feature=player_embedded[/youtube]