A Surprise from the Zambezi River

Sidney Hemming and her team aboard the JOIDES Resolution got a surprise when they began taking sediment cores from their first river site off southern Africa—about 10 times more sediment than expected.

Read Sidney Hemming’s first post to learn more about the goals of her two-month research cruise off southern Africa and its focus on the Agulhas Current and collecting climate records for the past 5 million years.

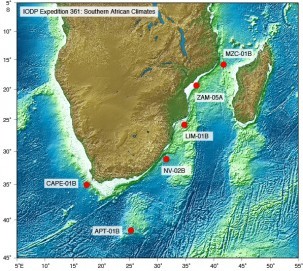

We have finished coring the Zambezi site and are on our way to the Limpopo site. Both are just off shore from major rivers that flow through Mozambique and should provide a record of the terrestrial climate variability in southeastern Africa through time, but we discovered a surprise. Based on short cores from nearby, as well as seismic surveys, we were expecting that the sediment accumulation would be 10 cm per thousand years. We were wrong by almost 10 times. The accumulation rate is approximately 1 meter per thousand years. Luckily, one of the scientists has been studying records from short cores, and the correlations to them is very clear even though the accumulation rates are so much greater, and we have two biostratigraphic datums that are further consistent.

So with our 200 meters of core we were only able to get back to 200,000 years instead of the 2 million years we anticipated. This is happy news on one hand, as this will allow some extraordinarily highly resolved records of climate variability back to approximately 120,000 years, and maybe (with small gaps) back to 200,000 years. But it is also disappointing from the view of the goal to get a long record of climate variability in the Zambezi catchment. It allows different kinds of questions to be pursued, and they are also very valuable. We feared encountering a bunch of sand, and that did not happen, so all in all this was a successful site, and we are still absorbing the change of approach that would be required to get the most out of it.

We should get to the Limpopo site at about midnight ship time (Cape Town time) tonight, and expect the first core on deck early Thursday morning. It seems highly unlikely that our estimate of sediment accumulation will be much different, but we are eager to find out! The location of our site is on the outside of a terrace feature in the indentation feature on the African margin (both the Zambezi and Limpopo enter the Indian Ocean in distinctive indentations on the eastern margin of southern Africa). Based on the seismic cross sections, the deposit is what is called a “plastered drift,” it is a body of sediment that is built up by bottom currents flowing southward along the margin. So even though the site is in the Limpopo area, its location relative to the currents is such that we may expect to get a similar record here as well. We will need to make some careful comparisons using the many existing short cores to establish how to best apply and interpret our methods.

Meanwhile, things are very busy on the ship. We were not able to complete the measurements and description of the final hole from the highly successful first Mozambique site before arriving here, and we are still working on the Zambezi cores as we approach the Limpopo site. We hope to keep up the pace so we will be finished with both soon. We expect the coring at Limpopo to take approximately two full days. Then we have about four days transit to our final site, CAPE, off the tip of South Africa. We want to have all three site reports completed before we arrive at CAPE since we will have no scrap of extra time after that!

Sidney Hemming is a geochemist and professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. She uses the records in sediments and sedimentary rocks to document aspects of Earth’s history.