A Study Offers New Insights Into the Record 2021 Western North America Heat Wave

Several weeks during summer 2021 saw heat records in the western United States and Canada broken not just by increments, but by tens of degrees, an event of unprecedented extremity. To what degree was it climate change, bad luck, or a combination?

The heat wave that hammered western North America in late June and early July 2021 was not just any midsummer event. Over nine days, from British Columbia through Washington and Oregon and beyond, it exceeded average regional temperatures for the period by 10 degrees C (18 F), and on single days in some locales, by an astounding 30 C, or 54 F. Among many new daily records, it set a new national benchmark for all of Canada, at 121.3 F in Lytton, British Columbia. The next day, the entire town burned down amid an uncontrollable wildfire—one of many sparked by the hot, dry weather. Across the region, at least 1,400 people died from heat-related causes.

Within weeks, scientists blamed the event’s extremity largely on climate change. Now, a new study in the journal Nature Climate Change affirms that conclusion, and for the first time comprehensively elucidates the multiple mechanisms—some strictly climate-related, others more in the realm of disastrous coincidences—that they say led to the mind-bending temperatures.

“It was so extreme, it’s tempting to apply the label of a ‘black swan’ event, one that can’t be predicted,” said lead author Samuel Bartusek, a Ph.D. student at the Columbia Climate School’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “But there’s a boundary between the totally unpredictable, the plausible, and the totally expected that’s hard to categorize. I would call this more of gray swan.”

The study pulled climate data starting in the 1950s together with daily weather observations from the weeks preceding and during the heat wave to form an intimate portrait. A core conclusion: Such an event would have been virtually impossible absent human-induced warming. It was impossible in the 1950s, but atmospheric warming since then has moved the needle to a prospective 1-in-200-year event—still rare, but now feasible. The researchers predict that if warming continues at even a moderate pace, such heat waves could hit the region about every 10 years by 2050.

Average global temperatures have risen less than 2 degrees F in the last century. But small upward increments may shift interactions between atmosphere and land in ways that drive chances of extreme temperature spikes far beyond just the average temperature rise. Boiled down to the simplest terms, the study says much of the 2021 heat wave arose from the multiplying effects of higher overall temperatures, including drying of soils in some areas. Additionally, about a third of the heat wave came from what the researchers call “nonlinear” forces—short-term weather patterns that helped lock in the heat that may also have been amplified by changing climate.

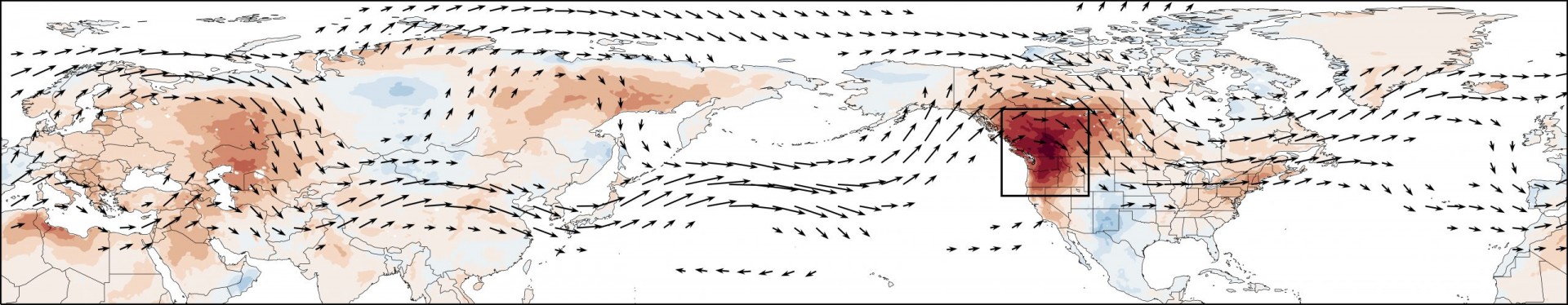

One major driver, they say, was a disruption of the jet stream, which normally carries air west to east across the Northern Hemisphere midlatitudes along a more or less circular path. Preceding the heat wave, though, the jet stream stalled and bent into huge waves, with four north-south peaks and troughs. These concentrated high-pressure systems underneath each peak; high pressure compresses air more and more as it approaches the surface, and this generates heat. One of those systems settled on western North America, then stayed there there day after day, creating what meteorologists call a “heat dome.”

Some scientists believe big jet-stream waves are becoming more frequent and extreme due to human-induced warming. The jet stream normally forms a boundary between frigid polar air and warmer southern air, but recent outsize warming in the Arctic is breaking down the temperature difference, destabilizing the system, they say. This idea is still being debated. That said, part of the groundwork for the new study was laid by coauthor Kai Kornhuber, who published a 2019 study identifying such meanders as threats to world food security should they hit multiple major agricultural regions simultaneously. In 2021, concurrent major heat waves tied to the meanders hit not just North America, but within a dome spanning much of Scandinavia, Eastern Europe, western Russia and the Caucasus; and another over northwestern Siberia.

Western North America’s was by far the worst. One factor, the authors say, was a series of smaller-scale atmospheric waves generated in the western Pacific Ocean. These moved east, and upon hitting land, latched onto the larger jet-stream wave and amplified it. Meteorologists could see these patterns coming some 10 days out, and thus accurately warned of the heat wave well in advance.

A longer-term key factor, the researchers say, is climate-driven drying that has overtaken much of the U.S. and Canadian west in recent decades, reducing soil-moisture levels in many areas. During the heat wave, that meant reduced evaporation of water from vegetation that previously would have helped counteract heating of the air near the surface. With less evaporation, in some places the surface more effectively heated the air above it. Indeed, the researchers found that the heat wave was most extreme in areas with the driest soils.

“Global warming is gradually making the Pacific Northwest drier,” said study coauthor Mingfang Ting, a Lamont-Doherty professor, pushing it into a long-term state where such extreme events are becoming ever more likely.

Extraordinary heat and drought continue to affect the region. In mid-October of this year, many daily temperature records were shattered with spikes more characteristic of high summer than mid-autumn. These included 88 degrees in Seattle on Oct. 16—a full 16 degrees above the previous daily record. The same day, there were records in Vancouver (86); Olympia, Wash. (85); and Portland, Ore. (86), its fifth consecutive day in the 80s. The hot, dry weather has sparked forest fires so fierce and widespread that on Oct. 20, smoke caused Seattle to see the worst air quality of any big city in the world, ahead of usual favorites like Beijing and Delhi.

“We can certainly expect more hot periods in this area and other areas, just due to the increase in global temperatures, and the way it shifts the probability of extreme events by huge amounts,” said Bartusek.