Report Charges ‘Nepotism and Neglect’ on Bangladesh Arsenic Poisoning

Two decades after arsenic was found to be contaminating drinking water across Bangladesh, tens of millions of people are still exposed to the deadly chemical. Now a new report from the group Human Rights Watch charges that the Bangladesh government “is failing to adequately respond” to the issue, and that political favoritism and neglect have corrupted the government’s efforts.

(This story was updated on April 8, 2016.)

Two decades after arsenic was found to be contaminating drinking water across Bangladesh, tens of millions of people are still exposed to the deadly chemical. Now a new report from the group Human Rights Watch charges that this is in part because the nation’s government “is failing to adequately respond” to the issue, and that political favoritism and neglect have corrupted the government’s efforts.

The report says Bangladesh’s health system largely ignores the health impacts of arsenic exposure. An estimated 43,000 people die each year from arsenic-related illness in Bangladesh, according to one earlier study. But the government identifies people with arsenic-related illnesses primarily via skin lesions, the report says, although the vast majority of those with arsenic-related illnesses don’t develop them. Those exposed are at significant risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease and lung disease as a result, but many receive no health care at all.

“Bangladesh isn’t taking basic, obvious steps to get arsenic out of the drinking water of millions of its rural poor,” said Richard Pearshouse, senior researcher at Human Rights Watch and author of the report. “The government acts as though the problem has been mostly solved, but unless the government and Bangladesh’s international donors do more, millions of Bangladeshis will die from preventable arsenic-related diseases.”

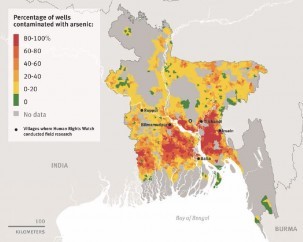

The problem mostly affects rural poor, who rely on as many as 10 million shallow tube wells for drinking water. The government and international agencies dug millions of these wells from the 1960s to the 1980s to replace microbe-infested surface water sources that were causing widespread disease and deaths. But by the mid-1990s, it was clear that naturally occurring arsenic in the groundwater was causing a whole new set of problems.

Earth Institute researchers have spent two decades working with Bangladeshi scientists and medical workers to combat the scourge. They have tested wells and investigated the source of the arsenic. And, they helped set up a health monitoring program and clinic in Araihazar Upazila, a subdistrict not far from the capital of Dhaka, to provide health screening and elementary care for individuals afflicted with arsenic poisoning.

Their work has helped establish links between arsenic exposure and many chronic diseases, including numerous cancers, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, diabetes and cognitive development delays in children.

The Bangladesh government attacked the problem with a widespread well testing and replacement program that has installed many deeper wells, which are far less likely to be contaminated. The deeper wells also are more expensive than the shallower, hand-drilled tube wells, so typically several shallow household wells would be replaced by one deeper, community well.

But Human Rights Watch found that that effort has fallen off, and has become laced with politics. The report also found “a serious lack of monitoring and quality control in arsenic mitigation projects.” In a “small but significant number of cases,” even government-installed wells are contaminated with arsenic above the national standard.

Despite all the work, it appears little has changed. From 2000-2006, testing found 20 percent of tube wells that provide water for some 20 million people contained arsenic above 50 micrograms per liter, the Bangladesh standard (the World Health Organization standard is 10 micrograms per liter). A 2013 study of drinking water quality showed a similar result.

The report lays out a series of steps the government and donor agencies should take to fix the problems.

“Although deep wells can often reach groundwater of better quality, government programs to install new wells don’t make it a priority to install them in areas where the risk of arsenic contamination is relatively high,” the Human Rights Watch report says. “Moreover, some national and local politicians divert these new wells to their political supporters and allies, instead of the people who most need them.”

Human Rights Watch wrote to the government to ask the reason for this approach, but no reply had been received at time of publication.

Alexander van Geen from the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory has been studying how arsenic gets into the groundwater—and how to fix the problem—for years. In a recent study, he and colleagues revisited how the deeper, safer wells were distributed and monitored. They found some of the deeper wells to be contaminated, for a variety of reasons, and that many wells were still not being tested. More significantly, perhaps, they saw that many of the deeper wells were being clustered in areas that were not considered higher priority because of higher levels of arsenic contamination. In some cases, those wells were going to households where access to outsiders was restricted.

Van Geen’s study noted that government policy allows local elected officials a say on how the money set aside for drilling wells is spent, and where.

“The clustering of deep wells and their frequent installation in areas where access is limited to the household of the land owner may indicate elite capture of a public good ostensibly intended to benefit the entire population,” the study’s authors said. “The influence of elected politicians on decisions affecting their constituency that should, in principle, be taken by non-partisan civil servants has been a growing problem in Bangladesh.”

Human Rights Watch undertook a broader study, analyzing data from about 125,000 government-installed wells. They spoke to 134 people, including villagers suspected of having arsenic-related conditions, well caretakers, government officials, independent researchers and staff at non-governmental organizations.

Pearshouse said the problem of political interference in decision-making “is widespread and pernicious. The policy of the main government rural water supply project from 2011-2015 had a nationwide policy allowing members of parliament to decide where half of all new government wells are located.

“Government officials told us that, rather than going to those who really need it, wells go to supporters and allies of members of parliament. One official told me: ‘Site selection of new tube wells is essentially all about politics. They give them to their political allies, their supporters, those close to them or those who work for them. It is very frustrating, they don’t consider the real needs of the people.’”

The report recommends that the government start targeting high priority areas for testing and new wells, and scrap the policies that allow political representatives influence in deciding who gets help.

It suggests a comprehensive strategy of testing and remediation, and making the decision-making process more transparent; improvement of basic health care in rural areas; better tracking of illnesses nationwide; and a nationwide public awareness campaign about the dangers of arsenic in drinking water. It also urges the World Bank and donor agencies like UNICEF to test and fix wells they have provided, push for a more aggressive strategy and do what they can to discourage political interference.

The Human Rights Watch report “is a valuable first step” that “highlights some of the potential issues,” said Mushfiq Mobarak, a professor of economics at the Yale School of Management.

Mobarak and van Geen are working on a follow-up study to map where people with political and economic influence live and compare that to how the deeper wells are distributed—“to see whether politics explains the distribution of deeper wells.” They’re hoping that solid data will help convince the government to change its policies.

“If [you can] say that X-percent [of well distribution] is driven by politics, and you can fix that problem and have wells distributed in a more equitable way, [that] with the same budget you can reach this many more people, that’s a powerful way to get back to the government,” Mobarak said.

Mobarak, who was born and raised in Bangladesh, and van Geen also will examine ways to convince more people to install their own deeper wells, which can cost five to 10 times as much as the shallow tube wells.

Van Geen had an additional suggestion: Rather than doing the water testing at government labs, the government should subsidize a network of private citizens who can go into the field and keep track of the wells. “With today’s technology—improved field kits, smart phones with GPS tracking, inexpensive ways of loading data—you could have government-certified testers going around and getting paid for it, and doing a good job,” he said. “You need an army of testers, a sweeping testing campaign, because wells keep getting installed.”

Right now many people just don’t know the status of their wells. Van Geen said widespread testing could help the push for more equitable siting of new wells, too. “If you have a village where people can tell the local government person that all our wells are bad … that should create the pressure,” he said.

You can read and download the 73-page Human Rights Watch report, “Nepotism and Neglect: The Failing Response to Arsenic in the Drinking Water of Bangladesh’s Rural Poor,” at the group’s website, here.

The research paper “Inequitable allocation of deep community wells for reducing arsenic exposure in Bangladesh,” by A. van Geen, K.M. Ahmed, E.B. Ahmed, I. Choudhury, M.R. Mozumder, B.C. Bostick and B.J. Mailloux, is available here.

You can read a story and watch videos on State of the Planet detailing the problem of arsenic in drinking water in Bangladesh, and the ongoing work by researchers from Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health, Barnard College and their colleagues in Bangladesh.