The Plate Tectonics Revolution: It Was All About the Data

The young scientists who led the plate tectonics revolution 50 years ago showed how asking the right questions and having access to a wide range of shared data could open doors to an entirely new understanding of our planet.

The plate tectonics revolution was a data revolution. The young scientists who led the charge 50 years ago showed how asking the right questions and having access to a wide range of data could open doors to an entirely new understanding of the planet.

This week, those scientists and the generations they inspired are meeting at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory to look back on their discoveries 50 years earlier and to discuss the scientific developments over the decades since that continue to build our understanding of the behavior of Earth’s tectonic plates.

In talk after talk as the symposium got underway, the conversation turned to data access and Maurice “Doc” Ewing, Lamont’s founding director, who changed the course of scientific investigation by creating an environment of constant data-gathering and faithful data-sharing across the institution.

It may seem normal to share data today, but in the early 1960s, scientists were more likely to collect only the data they needed and guard it closely. Manik Talwani, who followed Ewing as Lamont’s director and brought computerized data storage into the picture, recalled what Lamont geologist Bruce Heezen had told him about life at another institution: You went out on a research cruise, collected your data, then brought it back and stored it under your desk, where it stayed.

“At Lamont, it was one repository,” Talwani said. Ewing ordered that every ship collect all types of data every day, including at least one deep-sea sediment core, and those cores, magnetic profiles, and other data had to be shared and stored in an accessible way. “When the time came to interpret those data, that proved to be very, very valuable” – scientists could go directly to the data they needed. “People at other institutions ridiculed Lamont when Ewing asked people to take a core a day, no matter where you are – ‘what a ridiculous idea’. That one core a day was used in many, many ways,” Talwani said.

“The reigning philosophy at Lamont was that observations rule science,” said geologist Bryan Isacks. When plate tectonics burst onto the scene, Isacks and his colleagues mined Lamont’s data collections to develop theories of how the plates move.

Ewing himself thought the theory of sea floor spreading was incorrect, and he was very clear about that until the data changed his mind. Despite his own views, Ewing created an environment that encouraged young scientists to go after the evidence, the scientists said. Geophysicist Xavier Le Pichon described having a freedom at Lamont to do research and publish that he had rarely seen in other labs.

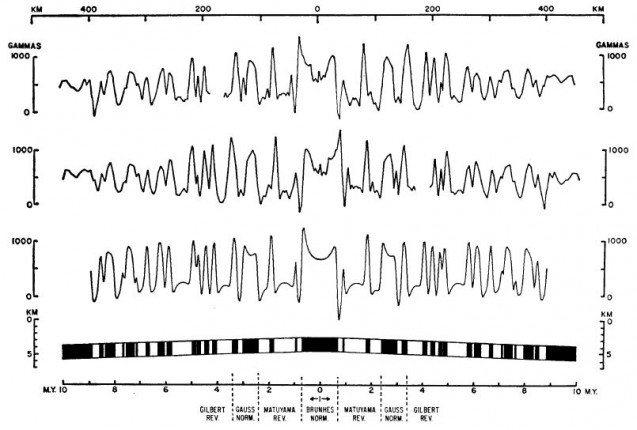

Lamont scientists had been mapping and studying the sea floor for many years, but the plate tectonics revolution really began when Walter Pitman discovered symmetry in a magnetic profile that had been recorded by the research vessel Eltanin as it crossed a mid-ocean ridge. The profile marked magnetic reversals captured in the sea floor rock below. The symmetry of the profile, with the mid-ocean ridge as the center line, showed that sea floor had formed at the ridge and spread outward to both sides over time. It was breakthrough evidence for Alfred Wegener’s ideas of continental drift and Harry Hess’s hypothesis of seafloor spreading. For Earth science, this was a paradigm shift.

Pitman’s Eureka moment set off a rush of discoveries in other fields across Lamont as scientists scrambled through data. Among them, Lynn Sykes used seismology to advance understanding of transform faults; Neil Opdyke, Billy Glass, and John Foster connected magnetic reversals to a new ability to date sediment cores from the ocean floor; and Isacks, Oliver and Sykes developed a theory for a mobile lithosphere that linked a broad range of seismological observations, incorporating ideas from Xavier Le Pichon.

“Only when we began to ask the correct questions did the answers begin to appear,” Opdyke said.

The revolution was possible because scientists had access to the data they needed. Sykes recalls that Lamont was one of only two places in the world with a complete collection of daily film chips from six types of instruments at seismic stations around the world. Those chips, and the practice of filing the monthly data shipments by date, became invaluable. “Previously, if you wanted to work on an earthquake mechanisms, you wrote to some 20 stations around the world, and it maybe took you a year to get those data,” Sykes said. At Lamont, he could quickly look up an earthquake on any given date.

“The greatness of Lamont – I attribute this to Maurice Ewing – it had a very strong purpose to discover the Earth,” Le Pichon said. “The priority was to get the data.” And those data made the difference. Scientists who disputed the early theories behind plate tectonics “jumped into the ship as soon as they saw the data,” he said.

Geophysicist Tanya Atwater, who worked on ocean floor plate tectonics in relation to the western United States and the San Andreas Fault, recalled, “Every now and then there would be an explosion (of scientific discovery) on the East Coast. The rest of us were working on this little problem and that little problem, and Lamont had the whole view.”

“It was a revolution,” said Bill Ryan, who talked in a video and audio podcast about the plate tectonics discoveries at Lamont that started when he was a graduate student and who organized the symposium. “It was successful because it was data observation driven.”

Learn more about the speakers’ talks at the May 23-24 symposium and watch them online.