Finding Microfossils off Southern Africa

Expedition 361’s newest sediment cores brought up spectacular foraminifera—translucent, glassy and “very pretty” throughout the ocean sediment.

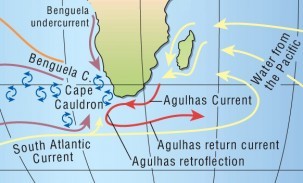

Read Sidney Hemming’s first post to learn more about the goals of her two-month research cruise off southern Africa and its focus on the Agulhas Current and collecting climate records for the past 5 million years.

Limpopo was awesome! We ended up with close to 4 million years of sediment from our latest coring site, off Mozambique near the Limpopo River. The accumulation rate for the last 2 million years is close to 10 cm per thousand years, so there is potential for highly resolved records in that interval. The accumulation rate between about 2 million and 4 million years is much lower, probably about a quarter, but that is also good news because we only had permission to go 250 meters, and if there had been more sediment we wouldn’t have covered nearly as much time.

The foraminifera are spectacular—translucent, glassy and “very pretty” throughout the whole sedimentary section. We do have a gap or two, as hard as we tried to avoid it, but we have overlap among holes for most of the site, and a continuous record back to close to 2 million years.

During coring at the Zambezi site earlier this week, the micropaleontologists had less to do since there were only two biostratigraphic datums (one foraminifera and one nannofossil), so nannofossil specialist Debs Tangunan made some cute art (above) with each of the biostratigraphers upon a fossil type of his or her specialty. Debs and Luna are the nannofossil specialists; Dick and Thiago are the planktonic (shallow floating) foraminifera specialists; Margit is the benthic (from the bottom) foraminifera specialist; and Jason is the diatom specialist. Jason’s pouting because most of our sites have not been good for diatom biostratigraphy, except the Agulhas Plateau. He has been a great sport, though, and has been helping with sample preparation and picking benthic foraminifera for a preliminary stable isotope record to help refine the age models for our sampling party.

We finished up at Limpopo this afternoon and now we are heading south to our final site, which is in the Cape Basin, and only eight hours from the harbor at Cape Town, South Africa. The catering staff put on a fantastic show for the 5-7 p.m. meal—it was sushi! And what a beautiful layout, with butter carved into the shapes of fish and various melons and other food. It was delicious and amazing!

During the transit to the Cape Basin, which will take a little over four days, we will have a busy time finishing the cores from Limpopo and the Mozambique Channel. We had to put ~1/2 of a hole’s worth of cores to the side to get the shallow sites completed, and we will finish up those cores as we transit to the CAPE site. We must have all the data collected and reports finished before we arrive at CAPE because we are going to have to devote our full attention to the CAPE site in order to get the report finished on that site before we get to port.

CAPE is located right were the eddies that constitute the “leakage” from the Agulhas Current enter the Cape Basin. So this site is going to be very important for tying together the story of how the Agulhas Current system is connected to global ocean circulation. The water depth of CAPE (as well as the other three of our deeper sites from this cruise: Natal Valley, Agulhas Plateau and Mozambique Channel) is in North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW). So we should be able to obtain some great co-registered records of how the shallow and deep ocean circulation are changing through time, as well as how the productivity and temperature and salinity have varied and how these are related in time to southern African climates.

Another exciting thing that is going to happen while we are at CAPE on March 26 is that co-chief scientist Ian Hall and stratigraphic correlator Steve Barker, both from Cardiff University, are going to be running a half marathon around the deck of the JOIDES Resolution at the same time the Cardiff Half Marathon is underway in the UK. Steve is a former Lamont postdoc and an adjunct associate research scientist at Lamont.

Their goal is to raise funds for a charity that supports children in South Africa. The small South African charity, located in the Western Cape, is called the Goedgedacht Trust, and it promotes education to help poor rural African children escape grinding poverty. We are also planning to provide some of the trust’s children with a tour of the ship during our visit in Cape Town. Ian and Steve will appreciate any support you (or your colleagues) can give! Donations can be made online. I’m planning to contribute, and I hope you will too.

Sidney Hemming is a geochemist and professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. She uses the records in sediments and sedimentary rocks to document aspects of Earth’s history.