Collecting More Than Just Seismic Data Along the Cascadia Fault

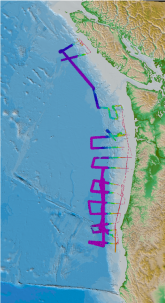

While researchers search for a megathrust fault off the Pacific Northwest coast, they are also helping to map the seafloor in high resolution and detect underwater methane seeps.

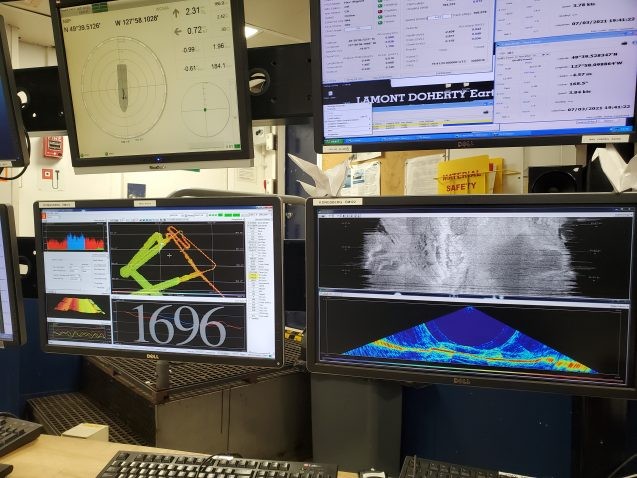

Down in the main lab of the R/V Marcus Langseth, you’ll find an array of monitors — 46, to be exact! — all displaying information about the data we’re collecting. While many of the screens are dedicated to monitoring the seismic data and the instrumentation related to collecting the seismic data, there are two screens that display data related to the multibeam echo sounder. A multibeam echo sounder is an instrument mounted to the hull of the vessel that emits sound waves in a fan shape beneath the ship. The sound waves travel through the water to the seafloor and back to the instrument. The time it takes for the sound waves to return is used to determine the depth of the seafloor, which gives us information on the shape of the seafloor — known as bathymetry. This information complements the deep subsurface imaging provided by the seismic data.

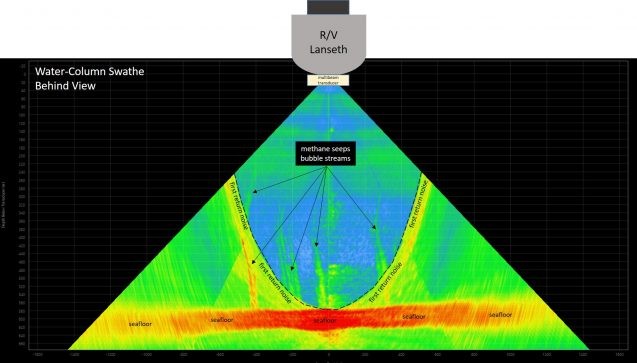

The two monitors dedicated to the multibeam allow us to control and see the data that is being collected. One of the screens shows the multibeam data in map view, allowing us to see the coverage and set the parameters for the instrument (Figure 1, left screen). The other screen is split into two windows that display the data in real time (Figure 1, right screen). The top window displays the seafloor reflectivity, a measure of the hardness or roughness of the seabed. The bottom window displays the data as a side swath, which essentially is a side view of the data as if we were looking at it from the behind the vessel.

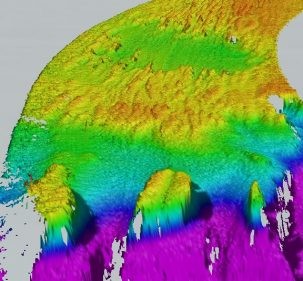

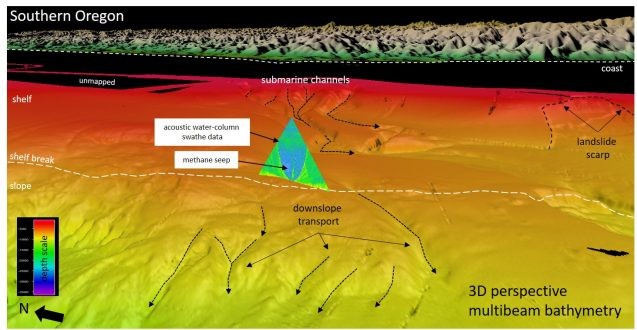

What exactly are we looking for in the multibeam data? In Figure 2, below, we can see a dynamic environment at the seafloor in southern Oregon with gullies, channels, and landslides all imaged along this small section of the margin. In addition to seafloor imaging, modern multibeam systems are capable of imaging gas bubbles within the water column. A methane seep can be seen in the new dataset which corresponds to a previously identified seep that may contain helium leaking from the Earth’s mantle. New imaging techniques (Figure 3) are allowing researchers to better locate where these methane seeps are emanating from the seafloor.

Careful review and interpretation of multibeam and sonar data in previous studies reveal thousands of methane seeps all scattered along the Cascadia margin. During our expedition, with the multibeam we have confirmed the location of some of these previously mapped seeps but have also identified some new ones. With careful and attentive eyes, you can spot these methane seeps in real time through the side-sweep window. However, the seeps are small in comparison to the spatial coverage of the multibeam, so they are really easy to miss and can disappear from the screen with a blink of an eye. Because of that, we mainly confirm and identify the methane seeps during the processing steps of the multibeam data. While processing the data, we are able to stack and filter to more accurately image and locate the methane seeps (Figure 3).

The multibeam data can reveal many important and interesting insights about the seafloor. Incorporating the new multibeam data collected on this cruise is one step further to having a complete high-resolution seafloor map and catalog of methane seeps along Cascadia.

Jeff Beeson is an assistant professor/senior researcher with NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory and Oregon State University.

Michelle Lee is a graduate student with Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.