Next Generation of Hudson River Educators 2021

High School Students Learn from and Educate Communities About Hudson River Ecosystems, by Marisa Annunziato, University of Miami undergraduate near peer mentor from Rockland Conservation and Service Corps

The Hudson River is one of the most important geographical features in New York, impacting the communities that lie along its banks. Despite the close proximity to the river, many of the communities along the Hudson are misinformed or know very little about it. Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory’s Next Generation of Hudson River Educators Internship (Next Gen) provides high school students a summer opportunity to uncover the truth about the Hudson River.

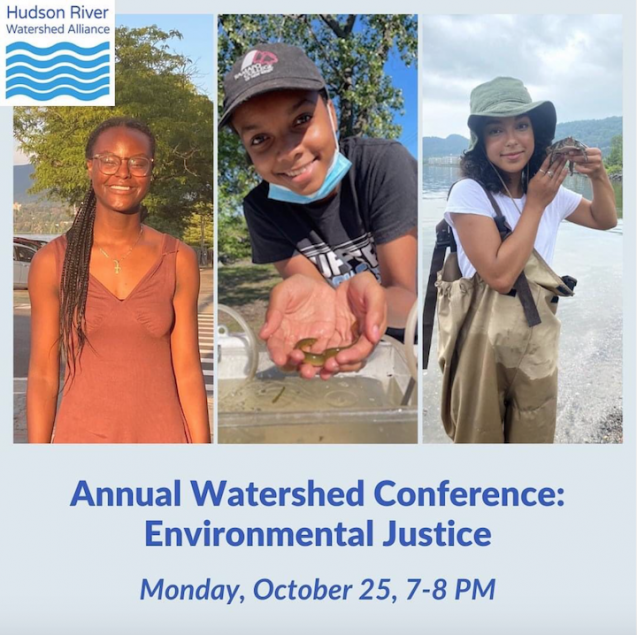

One of the central tenets of Next Gen is the focus on two way communication. This includes not only reaching out to community members to listen to their perspectives, but also coming back to share our findings and observations with that community. Too often this circling back to the community is overlooked. All of our summer participants were able to do so, however, through a series of meetings that included presenting their findings and providing recommendations to the Piermont and Haverstraw Village Boards, and presenting to local planning and community groups. Most recently, several of the students participated at the Hudson Valley Watershed Alliance annual conference as part of a panel of youth selected for their roles in creating regional change.

Below, we share some of the products created by our student interns as they developed their science communication skills and spread their newfound knowledge about the Hudson, debunking several long-standing myths and misunderstandings along the way. From using social media to creating unique games, the students created a range of educational outputs to educate the culturally, ethnically, and racially diverse communities along the Hudson River. The educational outputs that were created by the students are comprehensive and designed for all ages. They are showcased on Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory Field Station’s Instagram (@ldeo_fieldstation), Hudson River Field Station’s website, and were placed on display at the Rockland Conservation and Service Corps’ science fair event.

~~~~~~~~~

Social media is the first thing many of us turn to when we wake up in the morning. It is used by multiple generations for communication, entertainment, and education. Because of social media’s ability to target multiple demographics, Lamont’s Next Gen participants decided to make Instagram posts, TikToks, and YouTube videos to share our findings about the Hudson River with the public. We recognize the importance of educating others about the information we have been uncovering about the Hudson. While most people don’t regularly read scientific journals, many do visit social media daily. Using social media as a platform is a great opportunity to share scientific information that is not only comprehensible, but also digestible. It’s also a great way to share fun facts with people who are curious about their local environment.

We conducted interviews with friends, neighbors, and members of the Hudson community to uncover any misconceptions about the river. Our findings indicated that older generations tend to have a greater appreciation for the Hudson, while younger interviewees tend to have more misconceptions that have been passed along through the grapevine. This suggested that social media is the perfect outlet to target younger demographics and educate them about this mighty river.

Many of us documented our fun seining experiences and shared the species of fish and crabs we caught in the Hudson via social media. Some of us made day-in-the-life vlogs (video blogs), while others created MythBusters parodies to share the information we learned. We all enjoyed filming each other and editing our videos and learned a lot about communication as we tried to make short targeted posts. Sharing the knowledge we gained with our communities was incredibly fulfilling and important. Creating social media content was an amazing way for us to bond with each other because we completed all of our social media projects in groups or pairs. I had an amazing experience working on projects with my partner Monica, and we both developed a fascination with the mummichog, a small marsh loving type of killifish native to the Hudson, which is also known as a mud minnow because it buries itself into the mud during low tide when there is little water.

Find out more about seining, mummichogs and other aspects of the Hudson River at @ldeo_fieldstation on Instagram and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory on YouTube.

~~~~~~~~~

Myth Busting the Lower Hudson Estuary, by Monica Rivera, student at Tappan Zee High School

When the Next Gen educators interviewed members of the Rockland community to find out their perspectives and knowledge of the Lower Hudson Estuary, we learned that the river’s reputation misaligns with scientific facts. A majority of interviewees believe that the river is dirty due to what they see as the color of the water. Truthfully, the color of the water is due to high turbidity. Turbidity is the amount of cloudiness or opacity of the water. In the Lower Estuary, it is caused by rich nutrients, phytoplankton (photosynthesizing microscopic organisms) and algae, runoff after a rainstorm, and the movement of loose sediments due to tides, currents, wind, and turbulent mixing from the density differences between the fresh and saltwater.

Other common misconceptions are in regards to life in the Hudson. Many people believe that the Hudson is a lifeless water body. This is certainly not true. But many forms of life do bear the remnants of decades of prior pollution, which can be dangerous. Some Hudson fishermen believe that the fish of the lower estuary are safe to eat, yet most of the fish in the tidal Hudson should not be eaten, while some can only be eaten once a month. Age also plays a factor. Women below the age of 50 are encouraged to not eat any of the fish from the tidal Hudson, but men over the age of 15 can eat some fish that are designated as safe for consumption. Why do these restrictions exist? A large number of the fish are contaminated with chemicals, such as PCBs, that are unsafe to humans. PCB, which stands for polychlorinated biphenyl, is a human made chemical used as a lubricant and a coolant for machinery by many industries along the Hudson River. General Electric, a company located in the Upper Hudson was a major contributor, dumping PCBs for about 30 years into the Hudson and contaminating the water for years to come. Luckily, the Environmental Protection Agency found GE liable for their contamination and required them to conduct a 6 year clean up in the Upper Hudson of some PCB hotspots. This ended in 2015. Though the Hudson is much cleaner and safer than it was 20 years ago, the fish are still greatly affected by the persistent levels of PCBs that continue to circulate and settle at the bottom of the river. Despite the residual PCBs, the Hudson River is safe to interact with and it is even swimmable in many sections.

~~~~~~~~~

The Value of Field Sampling, by Janice Yohannan, student at Nyack High School

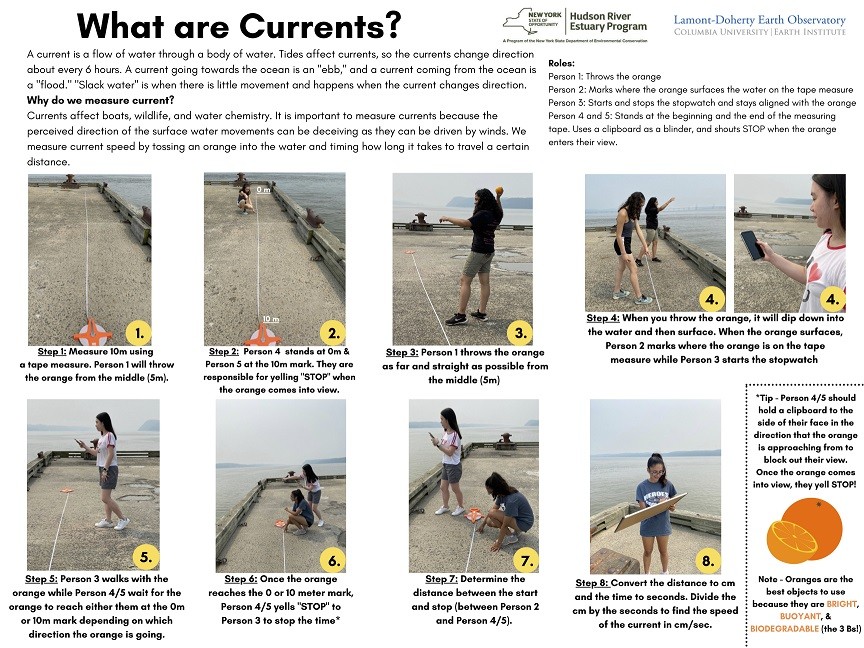

Over the summer, I found that the most incredible part of Lamont’s Next Gen program was being in the field two days a week. This allowed for hours of exciting field exploration and data collection. We were able to conduct soil and water chemistry tests, take sediment cores, and conduct habitat assessments to help better understand the environmental conditions in Piermont and Haverstraw as well as their implications for the ecosystem. We also learned to test soil for lead and measure turbidity, tides, and currents. We created step by step protocols to help others who want to do this type of sampling.

Our team often discussed the importance of conducting all these tests and experiments. In reality, there are so many factors that are involved when it comes to assessing the health of an ecosystem and understanding how different parts of this ecosystem work together. For example, we tested for levels of dissolved oxygen in the water, a measurement of the amount of oxygen available in the water for use by aquatic organisms. Since dissolved oxygen is necessary for the survival of aquatic life, monitoring it is essential in determining the health of the river’s ecosystem.

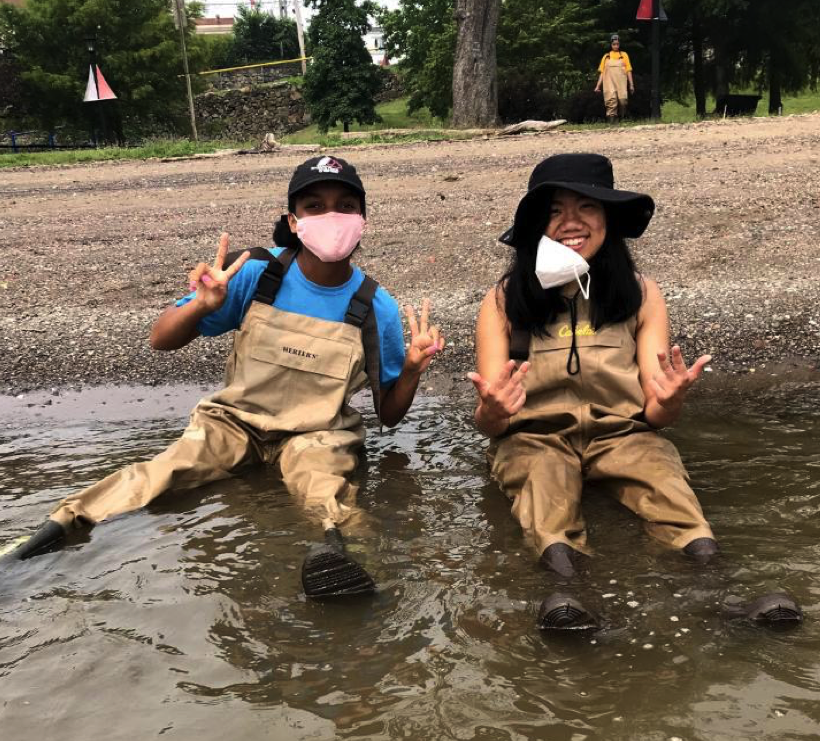

However, my favorite field activity was, hands-down, seining (shown in this Instagram post by Talha Uddin and Arianna Smith). Putting on waders and getting waist deep in water, trying your best not to fall in the river, and feeling the currents press the water all around you, is unlike anything I’ve experienced. I cannot think of a better way to connect with the river and with my local environment as a whole. Seining is also a super fun way to realize that the Hudson is full of life! From blue crabs to American eels to mummichogs (the small, marsh-loving killifish shown above in Jiaming’s section), we’ve caught and released beautiful animals. You can also view this short video made by Jiaming Li and Monica Rivera on the wildlife in the Hudson. Being a part of these incredible field experiences has greatly influenced my passion for environmental stewardship, and I am more excited than ever to protect my local environment!

~~~~~~~~~

Communicating Science Through Games, by Arianna Smith, student at Suffern High School

Games are a great way to bring people together, have fun, and be competitive, while also effectively educating others. The games created by the interns from Lamont-Doherty’s Next Generation of Hudson River Educators are the perfect combination of fun and information. For the past few weeks, we have been working on data games where our goal is to educate the public on a particular Hudson River topic. We utilized data from the Tuva Interactive Data Site and the Day in the Life of the Hudson and Harbor Database to create games that teach foundational Hudson science. The Haverstraw and Piermont groups collaborated together to create unique games that will be shared with the general public, and, hopefully, educate them about our thriving river ecosystem.

My partner Monica and I came up with a data game revolving around polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and fishing in the Hudson. PCBs are human made chemicals used widely in electrical equipment like capacitors and transformers. Starting in the 1940s and continuing until the ban on PCBs in the 1970s, General Electric and other companies dumped these chemicals into the river. Although many efforts have been made to clean the Hudson of PCBs, they still have an effect on the fish and wildlife in the river with certain fish accumulating more PCBs than others. Our game is called “Fishing Frenzy, ” where you are fishing the Hudson River using toy fishing rods to catch as many fish as possible in a given amount of time. Once the time runs out players have to release fish with high levels of PCBs, and whoever has the most fish left wins!

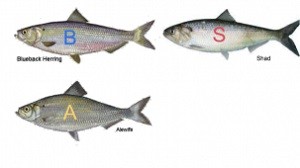

Our other friends created their own unique games as well. Jiaming and Talha created the game “Survival of the Herring” where you play as three different herring species and have to make it to the end of the board game; Janice and Sarah-Gail’s “Guess Who” Hudson River species game has players identify their Hudson species by guessing characteristics about them; Kaitlyn and Shania created a decision making game about water chestnuts and a data Jeopardy game!

Creating the game was a bit tricky as my partner and I had so many ideas that we wanted to incorporate. We had to go through each scenario of the game in our minds to predict the outcome and ensure it would conclude smoothly. This portion of our game making process was filled with many obstacles, but in the end we were able to create a fun, easy to understand game that educates people about the Hudson for people of all ages to enjoy.

Creating a game was one of my favorite parts of the program as I was able to take all the ideas stirring in my mind and bring them to life. Gathering feedback through ideas and suggestions from our peers and mentors was very helpful, and they played a big role in the development of our game. It was such a unique experience, and I hope the people playing these games have as much fun as we did making them!

~~~~~~~~~

Personal Interviews Gain Insights to Community Perspectives, by Charity Dikson, New School undergraduate near peer mentor from the Rockland Conservation and Service Corps

How can we best connect and share the value of the Hudson River and broader environmental resources with our communities in a culturally meaningful way? This is a major mission of students participating in The Next Generation of Hudson River Educators of Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory. They have dedicated their summers to an immersive and unique online and field-based program to learn about the diverse and dynamic Hudson River ecosystem. After diving into Hudson River science through field investigations, the students were to develop different educational materials that they could share with their friends, families, and communities to build stronger Hudson River stewardship. However, in order to develop culturally relevant informational outputs, the students first needed to learn from their communities regarding their thoughts and existing relationships that they have with the Hudson. Students interviewed multigenerational community members from Rockland County, New York to collect personalized perspectives about the Hudson River, and to learn more about the people in their communities.

Below one of our students summarized her experience interviewing community members this summer.

~~~~~~~~~

Interviewing Is Listening and Learning From Personal Stories, by Kaitlyn Canivel, Student Albertus Magnus High School

In science, we learn that it is always good to ask questions. Why is the sky blue? Why is the Earth currently getting warmer each year? Why do people in our communities think the Hudson River’s water is contaminated and that even touching it could be hazardous? Many agree that the best way to learn is to seek answers through asking questions, and what better way to learn from our communities than to ask questions of the people around us, in order to understand their perspectives.

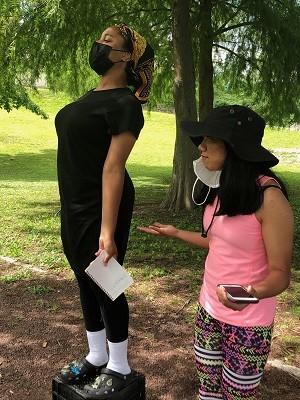

To uncover the best way to reach communities with meaningful educational resources about the Hudson River, interns from Lamont-Doherty's Next Generation of Hudson River Educators (Next Gen) interviewed the people around them. From friends to family, to neighbors and kind strangers, the Next Gen Interns inquired about their connections to, and views of, the Hudson River. The questions developed by the high school students addressed the interviewees’:

- Connection to nature

- Perspective of the Hudson

- Use of the river

- Connection to community

- Commitment to environmental stewardship

Through these interviews, the interns are able to develop a meaningful approach to educating their families, friends and communities about the Hudson River. While surveys may limit an individual to a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response, interviews allow for people to speak their thoughts and defend their opinions. Through this method of data collection, the conversation itself allows space for honest perspectives to surface, often introducing new viewpoints to the interviewer, allowing them to consider new ways of viewing a specific issue or subject. This method can also provide an emotional and thoughtful connection to others through discussing and sharing over topics that they might never have a chance to otherwise. Finally, interviewing helps to identify trends in communities.

From the interviews that I personally conducted, I learned that people’s perception of the Hudson was largely based on their experiences growing up. Hobbies, careers, and upbringings seemed to have caused those of different communities to have varied perspectives about the estuary. Many hold longtime misconceptions about the cleanliness of the Hudson, convinced its color proves it is unhealthy, yet its color results from natural sources and river processes, and the Hudson is home to more than 200 species of fish! In short the Hudson is an amazing water body that is not polluted as people believe!

One artist that I interviewed spoke frequently of the beautiful appearance and yet the unfortunate green-brown color of the Hudson water. Her interview focused on the power of the river, yet because of the water color, she believes it is polluted. Two lovely kids that I met on the waterfront told me of their travels to France, Italy, and their home in the Dominican Republic. They emphasized the stark difference between the crystal clear water of the Italian canals and Caribbean sea against the brown-green color of the Hudson. Another woman I spoke with mentioned her job as a logistics coordinator, and said that the Hudson is most likely polluted because of the vessels and boats that pass through the river. As someone who works with trade, it makes sense that she focused on the trade and transportation aspect of the Hudson River and how that influences her perspective. Yet another individual, a man from upstate in Saratoga, grew up witnessing the heated talk of polychlorinated biphenyl or PCBs in the Hudson and the dredging debate in the upper river, which fueled his misconception that the Hudson is most surely not a place one could swim.

Those who live right on the waterfront share extremely different views from those who don’t. Many waterfront residents swim in the Hudson and speak of the fascinating creatures they have seen in the river. With the sights of seals, turtles, and plenty of fish, it’s hard for them to say that the Hudson is toxic and polluted. These deviations among the individuals teach us that it is the little things in our lives that make our experiences unique and that sharing our stories through interviews, and understanding the context for opinions and perspectives, is so important.

I have also learned through this process that almost everyone in our communities truly loves nature and wants to protect it. Each person was involved in outdoor activities such as fishing, biking, walking, boating, or swimming in the Hudson, and expressed a personal dedication to the protection of nature through reducing the negative impact of trash through recycling. Some local residents of Haverstraw, with their close connection to the Hudson River, have practiced environmental stewardship through picking up litter.

The interviewees strongly agreed that it is important to get people engaged with the environment through programs, since we protect what we understand and see. The best way to do that, they said, was to motivate people to interact with it hands-on.

A majority of the interviewees did not know much about organizations that focused on researching, protecting, or educating about the Hudson River, such as Riverkeeper, Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, and the New York Department of Environmental Conservation Hudson River Estuary Program, or Lamont-Doherty. This is an important area for education we learned from the interviews. We also learned an effective approach to connect more people to the Hudson would be to use hands-on experiences. By using this method, many would be able to see the wonderful life that lives in the Hudson and appreciate its complex system, giving them a larger drive to protect this water body.

This holds true for many people who have interacted with the Hudson and have seen the biodiversity and life beneath the surface. One heartwarming moment was when we saw a young boy from Haverstraw develop a connection with a Florida soft-shelled turtle we caught at Emeline Park waterfront. During our interview, I saw him find a chip bag on the beach, and he quickly ran to the garbage to dispose of it correctly. “We don’t litter,” he said, “because it’s bad for the animals.

I personally can also say that this lesson holds true for me as well. After really seeing life in the Hudson for the first time through this program, my passion for protecting the environment has only grown stronger. After analyzing the data from the interviews I conducted, I found that being involved with nature and truly being immersed in it with hands-on education can instill a motivation to protect the life and environment around us. We realize that we aren’t so different from the life we see day-to-day: the trees that love to get some sun, the fish that keep swimming and moving along in life, and the animals that protect their young. Although we all lead different stories, we are all connected by our love for nature, and together, we can help create a better Earth for all life to live in.

~~~~~~~~~

From Lamont’s Next Gen program, I learned how valuable interviewing is as a way of gathering information. By understanding the context of everyone’s perspectives of the Hudson River, it has allowed me to observe small, important details that have played a major role in people’s opinions of the water body– details that I could not have seen if I used a survey or a different approach. These conversations have also made me feel more connected to the people around me, listening to their stories. The interviews have made me realize that everyone’s perspective of the Hudson, positive or negative, is influenced by their livelihoods. However, although we all lead different lives, we are all connected by our love for nature, and together, we can help create not just a better Hudson but a better Earth for all life to live in.

~~~~~~~~~

Issues of Inequity Explored by the Next Generation of Hudson River Educators, by Marisa Annunziato, University of Miami undergraduate near peer mentor from the Rockland Conservation and Service Corps

Environmental resources are often not allocated equitably, and in some instances, almost non-existent for communities of color when it comes to access to nature and environmental protection of these resources. The Next Generation of Hudson River Educators program of the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory (Lamont’s Next Gen) spent a week of the program focusing on local and global environmental injustice. Students learned about the disproportionate environmental impacts faced by marginalized BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) communities due to the development of highways that disconnects communities, industry and transit that degrade air and water quality, and the destruction of natural greenspace that offers a multitude of ecosystem services to the residents. This year’s interns were immersed in lectures, Ted-Talks, in-person debates, interactive activities and discussions surrounding topics of climate change and environmental racism.

~~~~~~~~~

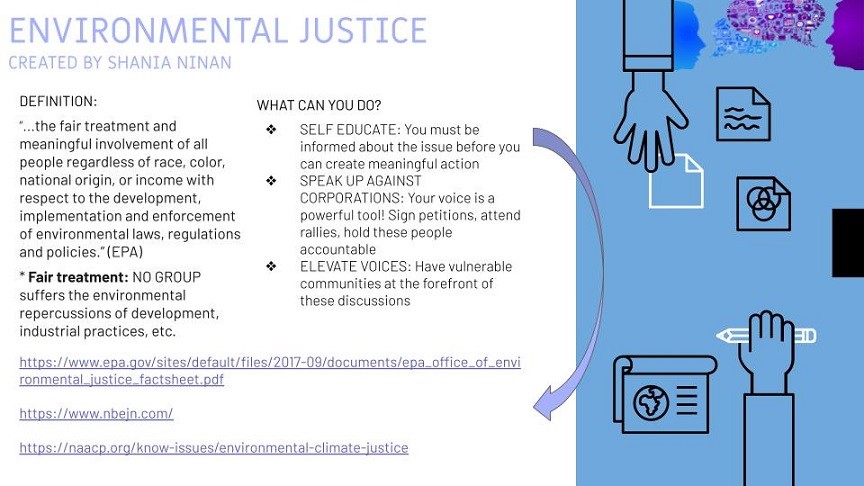

We Possess the power to Attain Environmental Justice, By Shania Ninan, Student Nyack High School

“What does environmental justice look like to you?” The first question of the day on a Monday morning Zoom call caught me off guard. Part of me was tempted to write pages and pages describing this idealistic utopian society while the other part of me could only produce a few words. A society where all people regardless of race, socioeconomic status, culture, sexual orientation, language, etc. can live with the resources and protection necessary to survive. It seems like such a simple concept: everyone lives under their inalienable birth rights. But unfortunately, environmental injustice is a prevalent issue in areas all across the globe.

The environmental justice movement has expanded over the past year, but are we as a community truly doing enough? This summer, Lamont’s NextGen examined this issue of environmental injustices both locally and on a global scale through captivating TedTalks, heavy conversations and debates, readings, etc.

Perhaps one of our most meaningful experiences was watching Majora Carter’s Greening the Ghetto TedTalk. Following the video, the discussion was short, not because we had nothing to contribute, but because of how powerful her message was. The combination of her intense demeanor and inspiring message and life stories forced us to truly sit back and reflect on this ongoing issue.

Carter discusses how those in positions of power are notorious for prioritizing the conditions of our economy, even if it’s at the expense of our people and environment. And who suffers the consequences of such choices? Marginalized communities. Local communities are infiltrated with long term development and infrastructure which have the potential to contaminate vital resources. Hearing her experiences living in areas around New York City which have become subject to such development was emotional, but Carter concludes her message by reminding us of the power we all possess; the power to influence decision makers and have the conversations similar to those that I’ve had over the past few weeks at Lamont.

Through my Lamont Next Gen experience, I have learned that recognizing our capacities to create tangible change is half of the process. Making our aspirations a reality is the next step.

~~~~~~~~~

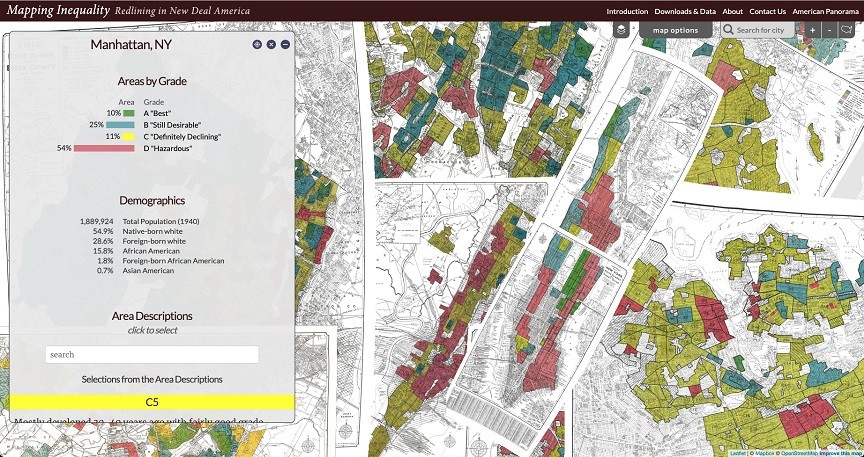

Fighting the Enduring Legacy of The Practice of Redlining, By Sarah-Gail Harvey, Student North Rockland High School

One of THE BEST Ted Talks I have ever listened to was one done by Majora Carter entitled “Greening the Ghetto” (linked above in Shania’s piece) Majora was born and raised in NYC and is in the process of creating change for the South Bronx in terms of environmental justice. Environmental justice is a topic that is not widely discussed in the news or even on social media. It has recently risen to the surface because of all of the social unrest that has been ravaging our nation. It has also recently become a passion of mine, as I endeavor to share my desire for change and equality in certain communities. I am a fellow Bronx native and also a young woman of color. Carter’s experience and tenacity towards her cause makes me feel empowered to fully understand redlining and what it means for communities that have mostly BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) residents.

According to the definition “In the United States, redlining is the systematic denial of various services to residents of specific, often racially associated, neighborhoods or communities, either explicitly or through the selective raising of prices” (Wikipedia). Unfortunately, redlining has a long history, and has made a negative impact on many marginalized communities. Local waterfront communities like Poughkeepsie, NY and Hoboken, NJ are examples of places that were redlined, where people were once hesitant to live as they were considered hazardous or high risk.

Railroads and air pollution have in the past deterred people from being interested in living in these areas. However with the clean up and attraction of the Hudson waterfront, gentrification has taken place. That is, wealthier families have moved in, realizing the worth and desirability of living along the waterfront, and this has pushed up housing costs and forced out longtime residents who may not have recognized the value of what they had. Marginalized communities do not always have access to information about their environment, and therefore sometimes lack enthusiasm to fight for it. After all, how can you fight for something you have no knowledge of? We must be more diligent in doing our research so that we can effectively protect what’s ours.

It is not fair that certain communities miss out on funding and support simply because of the income bracket and race of its members. As long as I have the ability to, I will advocate for the Bronx and other communities that experience this treatment. I want to give a special shout-out to Lamont’s Next Gen Program for conveying their interest in pushing for environmental justice for all.

~~~~~~~~~

Examining Climate Justice, by Talha Uddin, Student Spring Valley High School

From climate change to climate justice, the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI) lessons provided insightful information about the wider world around us. Initially established as a cooperative agreement between NOAA’s Climate Program Office and Columbia University's Earth Institute, IRI is located at the Lamont Campus. Their mission felt both impressive and intimidating “to enhance society’s capability to understand, anticipate and manage the impacts of climate in order to improve human welfare and the environment through strategic and applied research, education, and capacity building.”

I, along with the rest of the interns in the Lamont’s Next Gen program, gained a range of detailed climate information and can gladly say we were delighted to be part of the experience. Through our online seminars, we discussed topics that are often overlooked by mainstream media such as climate inequality and environmental justice around the world. I was introduced to terminology I wasn’t familiar with before, such as redlining (see Sarah-Gail’s piece above), and statistics like 56% of populations living near toxic waste sites are people of color. These were just small examples of the big takeaways I took from being part of these lessons.

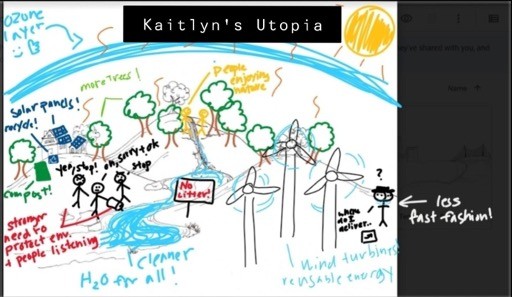

One lesson in particular that was not only engaging but overall insightful was when we were asked to create our ideal utopian societies. Our goal was to create an area that was environmentally friendly, including more renewable energy sources and better alternatives to the way we live today. My peer and friend Kaitlyn Canivel, was gracious enough to allow me to include her drawing to show an example of her idea of a utopian society.

Kaitlyn also provided some insights as to what each thing in her drawing represents. Overarching the whole image is the sun’s heat energy shown as orange lines, just below the blue lines show the ozone layer with its smiley face and thumbs up representing hope and optimism for a healthier Earth with reduced global warming and a more sustainable future.

The trees are a way to address global warming through carbon capture. She explains that trees serve as a positive symbol that provides Greenspace and increased environmental equity to communities still being impacted by the effects of redlining, a government and lender practice of withholding loans based on racial demographics. Greenspace provides multiple ecosystem services, including natural space for residents to recreate, and shade to cool down urban communities that suffer from the huge heat disparity that BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) communities face.

The composting bin is included to help sustainably eliminate and repurpose food that we consider waste. The people arguing represent her desire for people to better listen to the communities negatively impacted by unsustainable decision making and a stronger push to protect the environment and for people to listen to the community and take part in it activity.

The yellow stick figures illustrate the residents connecting and enjoying nature. Kaitlyn shares that currently the parks in her community are used less in comparison to other parks in Rockland County due to rumors of gang violence. The Amazon delivery person’s head is spinning in confusion because there is no one to accept their packages, symbolizing a community that does not support fast fashion or unsustainable products. Wind turbines, solar panels, and other sources of renewable energy were included supporting a healthy world for future generations. Our planet is our home. We need to turn these ideas into realities if we want our future to be bright and sustainable. IRI lessons were so impactful because they shed light on climate change issues that are not discussed enough. They helped me realize the importance of being educated on these topics leaving me feeling empowered to spread this information to others!

~~~~~~~~~

Conclusion, by Charity Dikson, The New School undergraduate near peer mentor from the Rockland Conservation and Service Corps

The mission of Lamont’s Next Generation of Hudson River Educators program is to provide high school students from under-represented communities a platform to engage and gain a passion for the environmental sciences. This prerogative then fuels these students to take what they have learned in the program and communicate that information back into their communities. Engaging students from these communities fuels a fire for more youth to get involved in the sciences and create powerful change.

Learning about examples of environmental injustice and environmental racism in their own communities and neighboring towns sparked powerful discussions this summer. Providing students with impactful lessons and discussions about environmental justice and other social issues further inspired them to create solutions.

Lamont’s Next Generation of Hudson River Educators Program is a program funded through a grant from the NYS DEC, with support from Old York Foundation, the Henry L. and Grace Doherty Charitable Foundation, Inc. and additional student support from the NSF INCLUDES program. For six weeks this summer the program ran a hybrid format with 2 field days (with teams in both Piermont and Haverstraw NY) and 3 virtual days each week. Eight high school students joined two Rockland Conservation Corps members and Lamont’s Laurel Zaima and Margie Turrin for an in depth experience.