Why I Care About the Bottom of the Ocean

It is the middle of the night and I am wide awake thinking about the ocean, specifically the bottom of the ocean. Is it rocky? Jumbled? Smooth? Rocky is bad. Jumbled is bad. Smooth is good.

Our group is sailing on the research vessel (R/V) Marcus G. Langseth, an oceanographic research vessel operated by Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory (where I work). The ship is a floating scientific laboratory, with the ability to study and take samples of the ocean water and sediments wherever we go. The scientists on board include seventeen researchers from nine institutions. In addition, there are 34 technicians and sailors who make sure the ship and scientific instruments are functioning properly so we can collect the data we need. The moment we leave the dock in Hawaii will be the culmination of almost a year of planning, a lot of hard work by the crew of the Langseth, and financial support from the U.S. National Science Foundation.

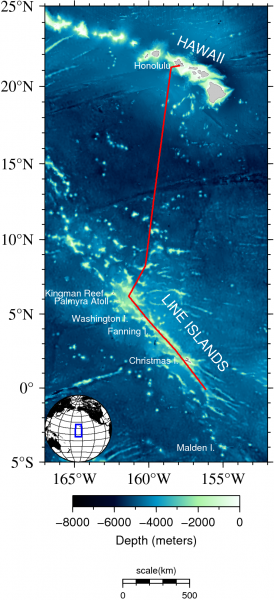

Our goal for this cruise is to collect cores of deep ocean sediment that we can use to study the past behavior of El Niño as well as the climate of the tropical Pacific Ocean. Although our studies focus on the Pacific Ocean, the results could tell us about many different areas of the globe. El Niño weather affects regions as far apart as Indonesia and New York State. In fact, El Niño events are responsible for the largest year-to-year changes in global weather. Our goal is to learn how El Niño has varied in the past so that we can develop better forecasts for the future of El Niño into the 21st century and beyond.

Over the next four weeks I will be writing a series of articles about our cruise. Topics will include El Niño, life aboard the ship and how we actually collect water and sediment samples from the ocean. Stay tuned!

In the meantime you can track where we are online.