Plankton Fishing in the Bering Sea

As Discovery Channel fans know, the Bering Sea supports one of the world’s most productive fisheries, accounting for more than 50 percent of U.S. fish and shellfish catches. The goal of our study is to understand how climate change is impacting phytoplankton, and ultimately the Bering Sea ecosystem.

I arrived in Kodiak, Alaska, two days ago with research technician Kali McKee. We are about to join scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory aboard the R/V Dyson for a two-week cruise. Our colleagues will be working on long-term monitoring of the ocean’s physics and chemistry and identifying larval fish in this important fishery. The target of our two-person team from Lamont is much tinier: plankton!

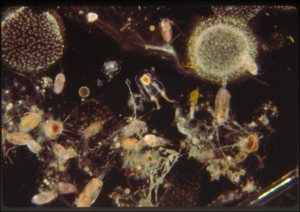

The word “plankton” comes from the Latin term for “wanderer.” They are the microscopic plants and animals in the ocean that form the base of all marine food webs. Most plankton are unable to swim, so they drift wherever the currents take them. Phytoplankton harness energy from the sun and “fix” it into carbon. They play a fundamental role in the carbon cycle, as well as in the cycling of oxygen (one of the by-products of photosynthesis), and various nutrients (e.g. nitrogen, phosphorus) in the world’s ocean. It is estimated that about 50 percent of the oxygen in the air that we breathe originated from phytoplankton! The way in which these tiny plants sink out of the surface ocean after they’ve reach high numbers represents a large removal of carbon that could otherwise return to the Earth’s atmosphere, and it makes sense that a lot of research is currently investigating the dynamics of these fascinating creatures.

Our goal in the Bering Sea is to see how much phytoplankton is here, and how the timing of the spring bloom is tied to the retreat of sea ice. Since 1997, the sea-ice coverage in the southeastern Bering Sea has been significantly reduced, due to warmer winter air temperatures. The downstream effect seems to be later phytoplankton blooms in years where little to no sea ice remains as the ocean warms in the spring. On top of that, the types of phytoplankton in those blooms appear to be different than in cooler years. Together, the timing of the spring phytoplankton blooms and the types of phytoplankton present can have significant effects on carbon cycling (which is important for understanding further climate change) and the food web. Zooplankton are the animal-like plankton which feed on phytoplankton and are themselves then eaten by everything ranging from fish to crabs to whales! As Discovery Channel fans know, the Bering Sea supports one of the world’s most productive fisheries, accounting for more than 50 percent of U.S. fish and shellfish catches. The goal of our study is to understand how climate change is impacting phytoplankton, and ultimately the Bering Sea ecosystem.

To understand these dynamics, we will spend the next two weeks taking water samples and looking at how much and what types of phytoplankton are present. We have a number of tools to help us make those determinations, and I will introduce you to some of those gadgets as we cruise along.

In the meantime, it has been a busy two days and a little rest is in order. The flights from New York took about 16 hours in total, and we have been busy setting up and securing loads of equipment (it can get rough out here!), conferring with our colleagues, and enjoying the phenomenal weather and long days in the 49th state. I spotted several of our national birds, the majestic bald eagle, while running errands in Kodiak, and this afternoon many happy sea otters lolled on their backs as we made our way through Kupreanof Strait. Whales, birds, and more fine weather hopefully await us, as do the plankton and the Bering Sea.

(unless otherwise noted, all photos: B. Stauffer)