New York’s Climate Buyout Plans Must Put Communities First, Experts Say

At the Managed Retreat conference, hosted by Columbia Climate School, researchers emphasized the need to work together with communities on climate adaptation.

In 2022, New York State passed the Clean Water, Clean Air and Green Jobs Environmental Bond Act. Among its many objectives, the act promises to invest more than a billion dollars toward flood protection across the state — including through voluntary private property buyouts.

What should a buyout program look like? This was the subject of at least one discussion at the Managed Retreat conference, hosted by the Columbia Climate School this week. Managed retreat means moving communities away from areas of high risk, and buyouts are one of the major tools to make that happen.

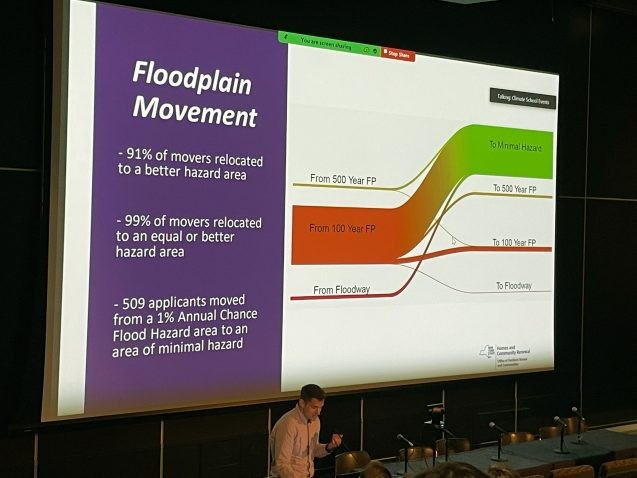

Designing an equitable buyout program is more complicated than it may seem. There are many questions to untangle, such as: Who has access to the buyouts? Who needs them the most? Are there safe and affordable destinations available? What happens to the people who get left behind? And what happens to the land that gets bought out?

In a workshop led by Cornell’s Linda Shi on Tuesday, panelists and participants shared their experiences and recommendations with David Burgy of the New York State Office of Resilient Homes and Communities, who is currently planning the state’s buyout strategy under the Environmental Bond Act.

A recurring theme was that buyouts need to be people-first, community-led, and tailored to different neighborhoods. Participants emphasized the need to listen to community members’ feedback, build trust, and leverage existing community networks to facilitate conversations and raise awareness.

In a different session, Malgosia Madajewicz of the Columbia Climate School’s Center for Climate Systems Research provided an illuminating case study on the effectiveness of community engagement in motivating and enabling residents of coastal areas to adapt to flooding.

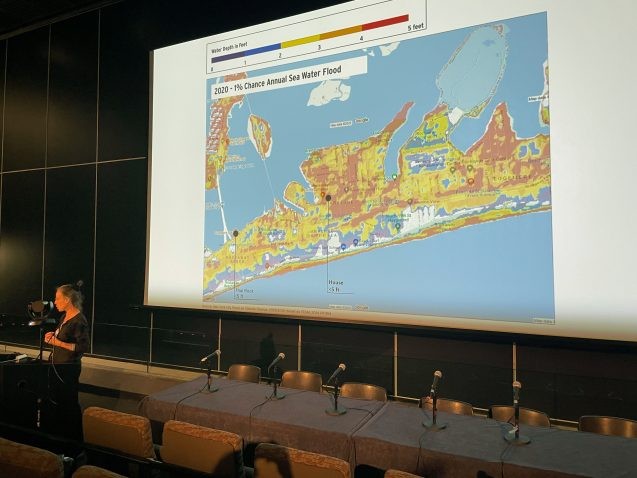

Madajewicz and her colleagues worked in the flood-prone peninsula of Rockaway, Queens, which was devastated by Superstorm Sandy in 2012. Despite previous outreach efforts, Rockaway residents were largely not taking action to protect themselves from future flooding. At the start of her study, Madajewicz found that many residents were unaware of their flood risk, and thought that their only options were to raise their homes or relocate. Most could not afford to elevate their home, and they didn’t want to move, so they disengaged from the conversation altogether.

Working together with 10 local community organizations, Madajewicz and her colleagues designed a program to raise awareness about flood risk in specific neighborhoods. They made pictures showing how high water levels could reach at familiar local landmarks, and calculated the estimated costs of not adapting — which, at one address, could tally upwards of $1.7 million over the next 30 years — versus how much money could be saved using a range of adaptation measures.

“They had heard a lot about the costs of raising the home, but it’s those benefits that they hadn’t really understood or thought about before,” said Madajewicz.

Over the course of the one-year study, “What was really tangible was the shift in people’s thinking about who is responsible for taking adaptation action,” Madajewicz said. “So there was a shift from that lack of agency … to thinking that residents really need to take responsibility for adapting. And particularly what was empowering to people was this idea of a range of options, where different options are appropriate for different houses.”

That personal empowerment led the community organizers to discuss bringing the information to others and taking collective action. They even started talking about relocation, “which wasn’t even on the table in the beginning,” said Madajewicz. She thinks the process can be scaled up to work in other communities as well.

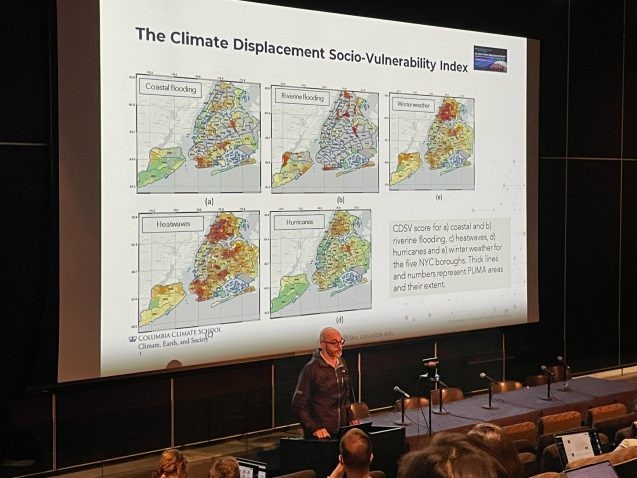

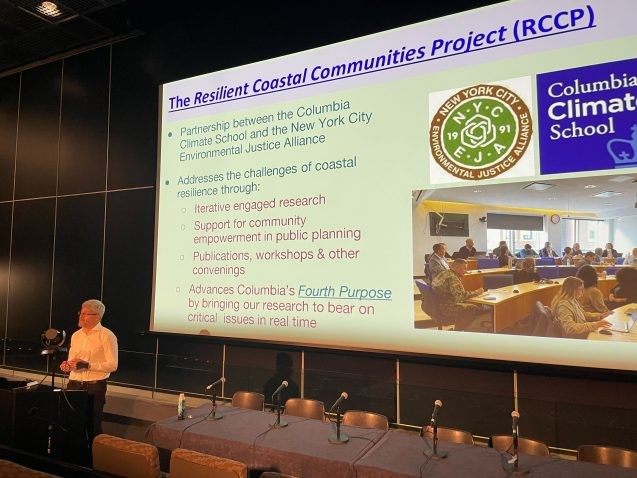

Paul Gallay of the Center for Sustainable Urban Design directs the Resilient Coastal Communities Project — a partnership between Columbia and the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance. Gallay spoke about how the project is working to empower communities in public planning around flood risks.

His advice, after interviewing community organizers: “Don’t bring completed plans to a community and expect them to throw roses and hosannas.” Instead, he said, planners need to approach communities with an opportunity for real dialog and interchange, and some degree of accountability.

“If we don’t bring the community effectively into planning, it will perpetuate and probably deepen the historic inequalities caused by histories of redlining and poor access to effective health care, sustenance, education and the ability to pass on intergenerational wealth,” he said.

Gallay emphasized that community involvement in resilience planning requires large investments of residents’ time; as such, he called on government programs to fund community capacity and participation.

“If you don’t have community empowerment, you’re not going to have effective coastal resilience,” he explained.

For his part, David Burgy said his team is in the midst of a statewide listening tour, and encouraged people to attend and share their thoughts and concerns regarding the Environmental Bond Act buyouts.

The Environmental Bond Act is not the first time New Yorkers have discussed climate relocation. Superstorm Sandy in 2012 spiked interest and debate around the topic, and many homeowners across the country have accepted buyouts to avoid repeated damages from hurricanes, coastal flooding and wildfires.

As climate change ramps up the pace and severity of many natural disasters, so too can we expect it to ramp up discussions of managed retreat. This week’s conference hopes to shape those future conversations and implementations to make sure they are equitable, informed, and community-led.