In India, Dirty Air Kills as Easily in the Country as in the City

A forthcoming study of northern India suggests that people living in rural areas are as likely to die prematurely from the effects of poor air quality as those living in cities.

A forthcoming study of northern India suggests that people living in rural areas are as likely to die prematurely from the effects of poor air quality as those living in cities. The study found that the sources of pollution in urban versus rural communities may be somewhat different, but the results are the same: high mortality linked to circulatory and respiratory problems. Air-pollution studies tend to focus on big cities, yet some 70 percent of India’s population dwells in rural areas, so the research may have wide implications.

“Ultimately, this tells us that outdoor air quality has received more attention in urban than in rural areas,” said lead author Alexandra Karambelas, a postdoctoral fellow at Columbia University’s Earth Institute. “It’s problematic not just because people are losing their lives.” She pointed out that other researchers have found that air pollution has significant negative effects on the economy as well.

Worldwide, at least 7.6 million adults and children are thought to die prematurely from the effects of air pollution each year. This includes about 1 million in India, where growing population density and a booming economy energized mainly by burning of biomass and fossil fuels are clouding the skies.

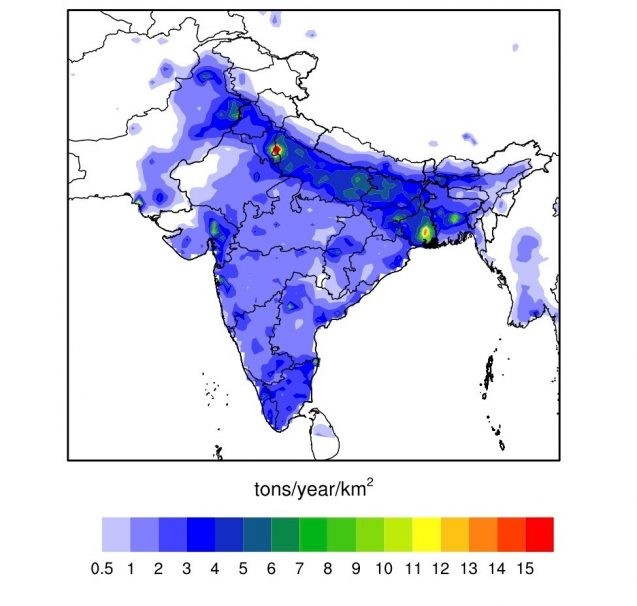

Karambelas and her coauthors modeled concentrations of two key pollutants in the northern part of the nation: fine particles generated by incomplete combustion of various fuels, and ozone, which forms in the air also as a byproduct of combustion. They then extrapolated premature mortality rates, using data from the Global Burden of Disease, a worldwide consortium that measures the health effects of pollutants and other adverse factors.

They estimated per capita rates of premature deaths among adults due to air pollution in both cities and rural areas, and found them to be similar at an average of 5.4 per 10,000 deaths each year (The researchers defined an urban area as a city or town with more than 100,000 people.) Three times more people died in rural areas as in cities: about 384,000 deaths versus some 117,000. (The discrepancy comes from the higher number of people living in rural areas.) The leading cause of such deaths was heart disease, followed by stroke and lung cancer. Due to limitations in the data, the researchers did not count deaths of children, so the overall death rate is probably greater, said Karambelas.. They also did not include nonfatal sicknesses, she said.

The study found that people living in the countryside get little break from the kind of pollution usually associated with denser urban cores. Fine black carbon particles from diesel emissions and other combustion sources were somewhat less prevalent in rural areas, but no dramatically so. That is because although there are fewer vehicles in the countryside, basically everyone burns wood, dung or other biomass for energy instead of using gas, electricity or other sources more readily available in cities. Overall, people across the study region were exposed to an average of about 70 micrograms per cubic meter–seven times the limit recommended by the World Health Organization. And due to the complex ways in which various precursor ingredients combine to form ozone, concentrations of that pollutant may actually be higher in the countryside than in the city.

The problem is not getting any better. For one, more Indians are driving cars; the number just in Delhi, the region’s main metropolis, is growing by about 10 percent a year. And, more people are moving to the country’s north, expanding the need for energy of all kinds. A separate 2016 study by a different group estimates that fine-particle pollution and ozone are cutting an average of 3.4 years off the lifespans of Indian citizens.

The study is slated to appear in the journal Environmental Research Letters. The other authors are Tracey Holloway of the University of Wisconsin, Madison; Patrick Kinney of Boston University; Arlene Fiore of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory; Earth Institute professor Ruth DeFries; and Gregor Kiesewetter and Chris Heyes of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria.