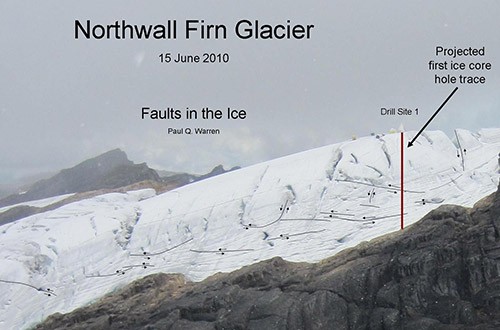

At the first drill site, faults in the ice (black lines with arrows) are obvious. Here, the ice is cracking and moving, as the glacier shifts around. Such faults are common on alpine glaciers, but movement could be hastened by the recent rapid melting. In analyzing these faults, Paul Warren has borrowed some terms from earthquake experts. According to him, most of the cracks are “thrust faults,” which means that older layers of ice have been thrust upward over younger ones. Others are so-called “normal faults,” where younger layers of ice have dropped below the older ones. Some faults were likely intersected by the coring (red line). It is important to know how the faults have moved, because their presence means that when studying the ice cores, one cannot simply assume that one is seeing the newest ice on the top and the oldest on the bottom. (click to view enlargement)