Confessions from a Former Coniferphile

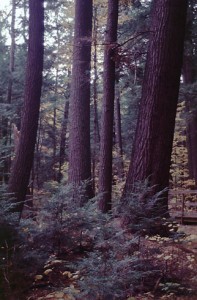

The first time I felt truly fanatical about coniferous trees was while walking among the great eastern white pine trees in the Adirondack State Park as an undergraduate research assistant and student.

I will admit it, there was a time when I loved conifers. Like, I was truly fanatical about coniferous trees. The first time I felt that way was upon walking among the great eastern white pine trees in the Adirondack State Park as an undergraduate research assistant and student. My first exposure to some truly impressive pumpkin pine was in the grove of old trees at the Pack Forest. These trees, charismatically represented by the Grandmother Tree, are truly impressive if you are seeing old-growth forests in northeastern North America for the first time. Soon after, I was taken on a hike to see a few large eastern white pine at the ranger school on Cranberry Lake. I was enamored.

As my educational path careened southward, I was brought to the large and old loblolly pines in the Congaree National Park in South Carolina. It was just a few years post-Hurricane Hugo and about half of the dense, massive loblollies were blown over. But, there were, and are, patches in the upper Coastal Plain that can give you a sense of how tree-mendous this forest was preio to Hugo. While not ancient, these trees are old for their species (the oldest tree was confirmed alive just a few days ago, making it at least 246 years old!). Please, go see these trees before they topple, especially in the heat of the summer. The scent they emit in the southern heat is savory.

My next stop was over the course of two years in the great longleaf pine ecosystem of the Deep South. The tree that is the foundation species of this highly diverse system is beyond charismatic. It is long-lived, has a phenomenal tap root that can look like another whole tree below ground, and long needles arranged like a basketball at the end of its twig. It is a glorious tree and ecosystem that deserves our attention and careful restoration across most of the Coastal Plain.

Not long after I finally landed in the Tree Ring Laboratory of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory for the first time, I was whisked away to the other side of the world to far, western Mongolia. Toward the end of that first, epic trip (think serious water illness; an outbreak of Black Plague; breaking out of the city quarantine at dawn; sharing a room with dead marmots, carriers of Black Plague; an overbooked plane back to the capital because of the plague; being wrongly held up at the border on the way home and missing our return flight….), we found what is still the oldest tree that I have personally cored: a 752-year-old Siberian larch in the Altai Mountains.

The next year I was on an expedition to the northernmost trees on Earth, the larch on the Taymir Peninsula. The scraggly small trees that were 400-600 years old were just lovely from so many perspectives…

Jeez, I’ve gone off-track here. I admit it. I still have the fever for conifer trees.

The point of all this preamble and this blog, however, is to point out that, yes, conifers are cool trees and while I will mostly ignore them on this blog, I dig them. However, I contend that the research field on the study of most broadleaf tree species is ripe, especially from a dendronchronological perspective. And, for this reason, but perhaps more for the fabulous diversity of leaf shape, bark texture, flower arrangement, autumn leaf color and overall funkiness of broadleaf species, I have moved on to adore broadleaf species.

Scientifically, we generally know much more about conifers than broadleaf species. Why this might be, I am not certain. I would think that conifers are the most studied type of tree for many reasons. Here are three:

1) They are highly valuable forestry species; foresters have been studying their natural history or life-history traits for centuries.

2) They live in extreme environments; forest ecologists and dendrochronologists trying to understand long-term climatic and ecological change focus on trees and forests in environments that are perceived to be the most sensitive to environmental change.

3) They live longer than hardwood trees; so, for many of the same reasons in #2 above, conifers are generally targeted by tree-ring scientists.

The goal of this blog, therefore, is at least twofold. First, it will be a champion for the wonderful, overlooked broadleaf species and their associated forests in the eastern United States and abroad. Of course, overlooked might be too strong of a word. For example, Liriondendron tulipifera (tuliptree, yellow-poplar, tulip-poplar) was an early species described by foresters as they began to scientifically study eastern forests. However, as will be demonstrated, our general knowledge of broadleaf species, including tuliptree, is much more limited than many coniferous species.

Second, as natural history is much less of a focus in modern ecological research, despite its necessity for long-term biological conservation, this blog will serve as an outlet for the natural history of broadleaf species learned through dendrochronology. While conducting paleoclimatological and paleoecological research through the examination of old-growth trees and forests, we often learn much about the natural history of individual species. However, this particular type of information rarely makes it into the scientific literature, as it is rarely the focus of our work (you would be so lucky to sit at a bar sometime with a handful of experienced dendrochronologists — the depth of their natural history knowledge is great). Because natural history appears to be dying out at American universities, the uncertainty around simple questions like, “How long can a tuliptree live?” and “How long might the shade-intolerant tuliptree persist in shade?” is high. This blog will serve as one place to answer some of these questions.

This blog will also serve up some of my favorite images of broadleaf species and forests. To close off the first post, here are some delightful images of the appropriately-named bigleaf Magnolia.