A Week of Firsts for This Arctic Nation

We are closing in on a week of intense focus and excitement for GEOTRACES and for the United States around the Arctic. President Obama became the first sitting president to visit Alaska, the US Coast Guard Cutter Healy with US GEOTRACES scientists completed the first unaccompanied US surface vessel transit to the North Pole, and the first group ever to collect trace metals at the North Pole! You might assume these three items are unrelated, but they are in fact tightly linked.

We are closing in on a week of intense focus and excitement for GEOTRACES and for the United States around the Arctic. It was barely a week ago (Aug. 31) that President Obama became the first sitting president to visit Alaska, refocusing the other 49 states on the fact that we are indeed an Arctic Nation. This historic first was followed closely by another, the Sept. 5 arrival of the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy with the U.S. GEOTRACES scientists on board at the North Pole, completing the first U.S. surface vessel transit to the pole unaccompanied by another icebreaker. Combined with this, U.S. GEOTRACES became the first group ever to collect trace metals at the North Pole. You might assume these three items are unrelated, but they are in fact tightly linked.

In convening the GLACIER Conference (Global Leadership in the Arctic: Cooperation, Innovation, Engagement & Resilience) in Alaska, President Obama focused on a region that is fast changing due to its fragility and vulnerability to climate change. The meeting timing aligned nicely with the U.S. assuming chairmanship of the Arctic Council, and was a perfect platform for the president to address climate change, an issue that he has tackled aggressively. Conference sessions on the global impacts of Arctic change, how to prepare and adapt to a changing climate, and on improved coordination on Arctic issues all align with the work of Arctic GEOTRACES, although tackled from a different angle.

It was while he was in Alaska that President Obama announced a commitment to push ahead the schedule for adding to the U.S. icebreaker fleet. The “fleet” has dwindled to just 3 U.S. vessels at present, and limits our ability to work in the Arctic. The goal of adding another icebreaker by 2020 will help to address this. “Working” in the Arctic for this Coast Guard cutter includes supporting the research that is critical to our being able to develop a baseline understanding of conditions and more accurately predict the future changes.

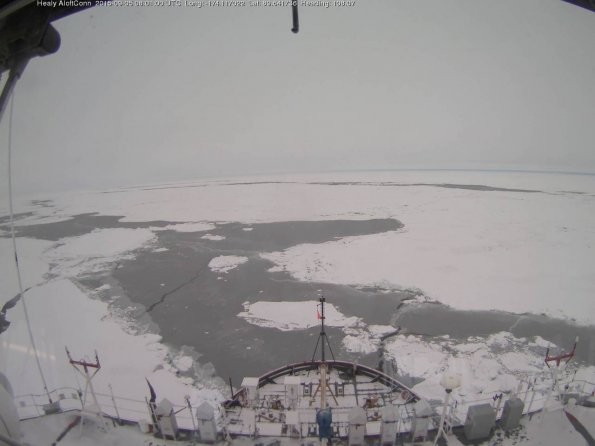

Evidence for change in the Arctic is found in the ability of the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy to cross the Arctic ocean along its longest axis (the Bering Strait route) and penetrate deep into the sea ice to make it to the North Pole unaccompanied. The ice has been thinner than expected and experiencing a much higher degree of melt. Ice stations, where the science team gets out onto the ice to sample, have been postponed because of safety concerns from the thin ice conditions. Everyone, including the captain, has been surprised by the conditions. The thin ice has increased the speed of travel. Although some thick (up to 10 feet) and solid ice has been encountered, much of the cruise has been spent traveling at up to 6 knots, and much less fuel has been used than expected because of this.

The last week has been action packed for all 145 people on the Healy. First. a “superstation” was run, a 57-hour sampling stop with a large number of samples collected in the ~4,000-meter-deep water. A super station includes additional hydrocasts and pump sampling for the groups like Tim Kenna’s, that require large volumes of sample water. This was also a crossover station with the German GEOTRACES cruise on the Polarstern. Crossover means some of the extra samples collected can be used to do intercalibration (check to see that the results compare) between the science teams on the two ships. The German ship will collect at the exact same location. With large sampling projects using multiple labs and sampling teams, intercalibration becomes extremely important for interpreting the results.

After our long superstation, the team went almost immediately into a dirty-ice station (ice that entrains sediment as it freezes). This ice can form in several ways: during the spring thaw when ice dams in Arctic streams force sedimented water out onto the ice, where it refreezes; during cold storms that churn up sediments in the shallow shelf regions to refreeze on the surface ice; and when shallow areas freeze solid, collecting sediment at the base, and later break away. Once the ice is formed, it moves into the Arctic circulation pattern, so identifying the source of the sediment can help us better understand the temporal and spatial nature of Arctic circulation. This type of ice has high value for Tim’s research, since short-lived radioactive isotopes are frozen into the ice with the sediments, providing a timer for the formation of the ice.

The dirty ice station was followed by an ice-algae station. Both of these entail stopping the ship and craning over two people in a “man-basket” where they can get out and sample (see image). This was followed closely by two full ice stations, where many groups went out on the ice to do their sampling; some for over 12 hours (brr). The second ice station had wind chills of -14 C.

Field time, especially in the polar regions, is expensive and limited, so while in the field it is critical to complete as much science as possible. Sleep happens later when the team is back home.

Lamont Note: As part of the Healy’s instrument package, they standardly carry a CO2 instrument from Lamont’s Taro Takahashi. This was onboard when the Healy reached the North Pole (89.997 °N). The partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) in seawater was found to be 343.3 micro-atmospheres at the water temperature of -1.438 °C. This is about 50 micro-atmospheres below the atmospheric pCO2 of 392.7 micro-atmospheres, and indicates that the Arctic Ocean water is rapidly absorbing CO2 from the air. The measurements confirm that the Arctic Ocean is helping to slow down the accumulation of the green house gas in air and hence the climate warming.

Margie Turrin is blogging for Tim Kenna, who is reporting from the field as part of the Arctic GEOTRACES, a National Science Foundation-funded project.

For more on the GEOTRACES program, visit the website here.