Upcoming Scientific Fieldwork: 2014 and Beyond

Earth Institute field researchers study the planet on every continent and ocean. Projects are aimed at understanding the fundamental dynamics of climate, geology, ecology, human history and more. Here is a partial list of upcoming expeditions.

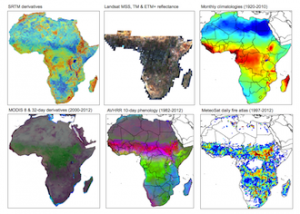

Earth Institute field researchers are studying the planet on every continent and ocean. Projects are aimed at understanding the fundamental dynamics of climate, geology, ecology, human history and more. Many deal with practical applications ranging from agriculture and water supplies to petroleum extraction, adapting to climate variability, and natural hazards such as earthquakes and tsunamis. Above, a map of projects; click on location for thumbnails. Below, a more detailed list of expeditions in rough chronological order. Work in and around New York City is listed separately toward bottom. Unless otherwise stated, projects originate with our Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. For expedition blogs and images from the field, see our Features Archive. Whenever logistically feasible, journalists are invited to join expeditions, or otherwise cover the work; further images are available for many projects. This list will be updated through the year. (Note: The map above has been edited to reflect projects starting up or ongoing in 2015. You can find out more about the current research through our 2015 guide to scientific fieldwork.)

LAST UPDATED: JULY 22, 2014

U.S. AND INTERNATIONAL

SOUTHERN GLACIER HISTORY Rock sampling and mapping, south New Zealand JAN 13-MAR 4, 2014

Past advances and retreats of glaciers contain vital clues about the workings of the global climate system. In the glaciated mountains of southern New Zealand, a team is collecting rock samples and drawing maps that show past positions of ice there in great detail over the past 13,000 years. Team members including Aaron Putnam will travel by foot and helicopter from base camps in the Ben Ohau range to collect samples for surface-exposure dating, from boulders left by moving ice. Among other things, their studies show that advances and retreats closely track surface temperatures of the Southern Ocean as well as air concentrations of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide. But wind patterns and other factors may affect the system, causing some regions to react faster or slower to CO2—perhaps a useful lesson for today. Expedition involves rough trekking through rugged landscape. Related: Watch a movie on the team’s exploits / Nature study on New Zealand glaciers

IS EAST ANTARCTICA MELTING? Oceanographic expedition JAN 29-MAR 16, 2014

East Antarctica’s Totten Glacier system is among the largest and least explored on earth. It drains one-eighth of the vast East Antarctic Ice Sheet, and if it collapsed, it would bring devastating sea-level rise. Aboard the icebreaker N.B. Palmer, polar scientist Bruce Huber and colleagues will collect oceanographic measurements to study how sensitive this region may be to climate change. Recent satellite data indicate that the Totten is losing ice at an accelerating rate, and aerial surveys of its drainage system suggest that it has been a major pathway for earlier glacial advances. During the six-week expedition, researchers will use a variety of instruments to peer into and through the frequently ice-choked waters nearby to understand past and current changes in the ocean, ice and ocean bottom. They will also see if warm water may be eroding Totten Glacier at its snout, as appears to be happening in parts of West Antarctica. The ship departs/arrives Hobart, Tasmania.

MELTING ANTARCTIC ECOSYSTEMS Long-Term Ecological Research, western Antarctic Peninsula JAN-FEB 2014

For nearly 40 years, U.S. scientists have been monitoring the effects of climate change on the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula—the part of the continent that extends the farthest north, and which has been hit by skyrocketing temperatures, far more rapidly than nearly anywhere else on earth. From Palmer Station, an island outpost run by the U.S. National Science Foundation, and part of a global network of Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) stations, researchers have witnessed stunning changes: a sea-ice season that is now three months shorter, and a steep drop in phytoplankton in some places that in turn has led to declines in krill production and penguin populations. Hugh Ducklow, a biogeochemist at Lamont-Doherty, is the lead principal investigator of the LTER Project at Palmer Station. With Lamont oceanographer Doug Martinson, Ducklow and other colleagues will spend two months aboard an icebreaker taking measurements of biota and the physical qualities of the water, and collecting samples on land and at sea. At Palmer Station itself, associated scientists will study penguins and do other studies related to the shipborne expedition. This year, the program will add a new team that will for the first time initiate a long-term study of Antarctic whales. Related: Trailer for film about Palmer due out summer 2014

FAST-MOVING ANTARCTIC GLACIERS Rock sampling and mapping, eastern Antarctic Peninsula FEB-MAR 2014

On the fast-warming eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula, in recent years huge ice shelves have disintegrated, and glaciers thinned and accelerated their push to the sea. Along with Argentine colleagues, glacial geologist Michael Kaplan is working to put current events into the context of natural climate swings in the last 20,000 years. Working out of Argentina’s Marambio Base and remote field sites, the team will travel by helicopter to knock out samples of exposed rocks on and around James Ross Island, and the now-collapsed Larsen A ice shelf. Later, back in the lab, they will use cosmogenic isotopes in the rocks to date the ebbs and flows of glaciers, in hopes of understanding how these correlate with past climate changes. They hope to pair their observations with similar work they have been doing in New Zealand and South America to form a clearer climate history of the southern hemisphere, and better predict the future. Team is led by Jorge Strelen of Argentina’s Cordoba University. Related: Film about the team’s work in New Zealand

HOW HIGH DID SEAS GO? Sampling ancient shores, Argentine Patagonia FEB 1-14, 2014

About 3 million years ago, during the Pliocene, earth was warmer than today and ice sheets collapsed, causing sea levels to rise—but how high? Paleoclimatologist Maureen Raymo, postdoctoral researcher Alessio Rovere, and a team from several institutions are crisscrossing the globe to collect and precisely date shells and sediments from exposed Pliocene shorelines. In February, the team travels near the tip of South America, along the coast of Argentine Patagonia. Past fieldwork has been done off the coast of Tuscany and in South Africa, Kenya, Australia, India and along the U.S. southeast coast. After correcting for movement of shorelines due to tectonic activity and loading and unloading of ancient ice sheets, they aim to pinpoint past sea levels across the world. The key question: To what extent did melting from the great ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica contribute to rises during a period where temperatures averaged just 2 to 3 degrees Celsius warmer than today—a mark that many scientists think may be reached by 2100? How much ice melt and sea level rise should we expect in the centuries ahead? Rovere is also involved in a project to use camera-equipped aerial drones to monitor erosion along modern coasts in Italy and elsewhere. Related: Pliocene Maximum Sea Level (PLIOMAX) web page / How High Could the Tide Go? (New York Times) / NY Times slideshow on the research / Article on drone use

DRYING IN THE HORN OF AFRICA Coring ancient trees, Ethiopian highlands FEB 15-MAR 1, 2014

Tree rings hold records of past rainfall and temperatures that have allowed scientists to plot past climate swings in many parts of the world. One place badly lacking samples is the Horn of Africa, which has seen a decline in rainfall over recent decades—a trend that probably has helped stoke continued violence in this already arid region. A team including dendrochronologist A. Park Williams will travel through the highlands of western Ethiopia to collect cores from juniper trees that may be 300 to 400 years old. Many of the oldest may be found in the protected yards of ancient underground Christian churches, scattered throughout the region. In a rugged landscape ranging from desert to forest, the team—led by researchers from the University of Swansea, Wales—will travel by vehicle and foot, working elevations up to about 12,000 feet. The cores may illuminate past climate history, as well as help scientists understand what is driving the current drying, and whether it is linked to global warming. Analyses will include conventional measurement of yearly rings, and more advanced investigations of oxygen isotopes that signal patterns of air flow, and where past moisture has come from. The work hooks in with research by Bradfield Lyon and others at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society, on the causes of drying in this region. Related: Earth Institute videos on Horn of Africa drought / Food insecurity in the Horn of Africa

WIND AND THE CO2 CYCLE Sediment coring, south New Zealand/Auckland Islands FEB 2014

The westerly winds that circle the Southern Ocean not only control rain in the southern hemisphere; they drive ocean circulation in a way that strengthens or slackens the ocean’s uptake of manmade carbon dioxide from the air. In recent years uptake has slowed and rains decreased, apparently due to the winds’ moving south in response to human destruction of the Antarctic ozone layer. To understand how this may affect global climate in an age of rising CO2, a team working on land and at sea will track natural variations in the westerlies over the last 16,000 years. Researchers including paleoecologist Jonathan Nichols will start in the southwest of New Zealand’s South Island, coring layers of plant material from lake bottoms and bogs that reflect changes in the westerlies. They will then sail on the University of Otago’s research vessel Polaris II to work in the uninhabited Auckland Islands. The ship will also take sediment from the bottoms of fjords within the islands. Some crew will count and observe whales—a project unrelated to the climate study. The trip will take about three weeks. Related: Video on Nichols’ bog work in Alaska

TURNING CO2 TO STONE Underground carbon injection/drilling, Reykjavik, Iceland ONGOING-SPRING/SUMMER 2014

Volcanically active Iceland is so rich in geothermal energy, it is considering expanding production for import to Europe via cable. But pumping heat from the ground to generate electricity also brings up gases, including carbon dioxide—the same as fossil-fuel-burning plants. In an effort to put the CO2 back, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and cooperating institutions are running the CarbFix project. This aims to inject the CO2 back into the volcanic basalt from which it came and turn it into a solid mineral similar to chalk, via natural chemical reactions. A 200-ton test injection last year suggested the reactions are not only taking place, but locking up carbon even faster than expected. This spring and summer, the team plans to inject 4,000 tons at a second site. They will also drill down 1,800 feet to recover cores from the first site, to get a close-up look of what happened below as the carbon solidified. This process may eventually be applied to CO2 emissions from conventional fossil-fuel plants elsewhere, obviating the fear of leaks often connected with such experiments. The project is being done in conjunction with the University of Iceland and Reykjavik Energy. Geochemists Juerg Matter and Martin Stute are the lead scientists for Lamont. Related: CarbFix project website / Article on initial tests / Image gallery / Science magazine report on the project

HAZARDOUS BANGLADESH Studies of rivers, faults, sediments FEB-MARCH 2014/ONGOING THRU 2015

Teams from Columbia and Vanderbilt universities are assessing interrelated natural hazards in Bangladesh, earth’s most crowded nation: earthquakes, shifting rivers, and sea-level rise. Not only is most of Bangladesh close to sea level; it is hemmed in by active tectonic boundaries. Major quakes could cause mighty rivers to shift course suddenly—something that the work suggests may have occurred previously. Seismologist Leonardo Seeber will travel for two weeks with colleagues to survey surface geology in southeast Bangladesh, and in neighboring India. In the remote southerly swamplands and the capital of Dhaka, Lamont geophysicist Michael Steckler will monitor instruments recording natural sinkage and other movements of the surface. Seismologist Won-Young Kim has helped Bangladeshi colleagues greatly expand a network of seismometers, and will spend several weeks visiting instruments and teaching. In a related project, scientists are trying determine to what degree people may be able to adapt to rising sea levels. As part of this, remote-sensing specialist Chris Small and colleagues will do a series of studies on the landscape in the southwest. Related: Watch a documentary about the project / Project website / Project blog / Science magazine article

THE GALAPAGOS PLUME AND THE CENTRAL AMERICA LAND BRIDGE Geologic fieldwork, Panama, MARCH 8-16 (or later) 2014

Like the Hawaiian islands, Yellowstone, and other volcanic landmarks, parts of central America and the Galápagos Islands are made of magmas from a mantle plume—an upwelling of material from the deep earth over which tectonic plates are moving. This plume has provided material for one of earth’s pivotal features: the narrow land bridge joining North and South America, at the isthmus of Panama. The land bridge has played a key role in global biological evolution and climate; it cut circulation between the Pacific and Atlantic, while joining two great continents, and their biota. Geochemist Cornelia Class and petrologist Esteban Gazel are studying rocks produced by the plume to gain a greater understanding of these momentous events, as well as the basic deep-earth processes that drive such eruptions. In September, they will collect samples from outcropping rocks along the Pacific coast on the sparsely inhabited Azuero peninsula. They will work largely along beaches, jungle riverbeds, and small islets near shore where vegetation and dirt have been washed away. Many sites can be accessed only by boat and/or swimming. Among other things, Gazel and others believe that the plume, now centered around the Galápagos Islands, is cooling, and may be in the throes of a death that will come millions of years from now. Related: Gazel paper in Nature / Story, video and photo essay on the project

WANDERING RIVERS Surveys of bed physics, Shimanto River, Shikoku, Japan MARCH 2014

Rivers meander through diverse environments, from Greenland to the Amazonian flood plains. What accounts for their wandering tendency? Scientists are studying one of world’s finest examples of a meandering river—the Shimanto, on the sparsely populated island of Shikoku. It cuts through relatively soft bedrock on a beautifully sinuous course. With few dams or other human influences, the Shimanto is a perfect place to study natural erosion patterns and how rivers change shape through time. In the second year of a three-year project, Lamont scientist Colin Stark will study erosion of the bottom and sides during floods, landslides and other events. With 3-D photography and precise topographic maps gleaned from airborne laser data, he and colleagues will bring their observations into the lab to test their ideas about the process. Related: Previous study of river erosion in Taiwan

MANAGING BIG CLIMATE SWINGS Training for Famers, Laos MARCH 2014

During the past decade in the fertile lowlands of Taleo village in the Champhone District of Laos, farmers have been struggling with what they describe as unprecedented swings in climate—severe drought and floods in the same growing season, false onset of monsoon rains in one year, and early onset in the next. All have reduced yields, and farmers fear that the historical knowledge that had helped them anticipate past fluctuations no longer serves them. Staff from the International Research Institute for Climate and Society will train farmers in climate risk management, as part of a wider program sponsored by the International Fund for Agricultural Development. The field-school series is aimed at providing poor rural dwellers with the skills and support systems to make informed decisions about crop management. The two-year project will also have demonstration sites in Indonesia and Bangladesh. IRI staff will also work with the Laotian National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute and Department of Meteorology and Hydrology to enhance development of climate services to farmers. Contact: Asia/Pacific program coordinator Erica Allis.

HISTORIC CORAL REEFS UP CLOSE Student field trip, Barbados MARCH 15-22, 2014

Fossil coral reefs fringing the Caribbean island of Barbados are a landmark in modern climate science. It was here that scientists found the evidence to work out how earth’s orbital cycles drive the waxing and waning of ice ages, and thus sea levels. Participants will study magnificent reefs both on dry land, and underwater, and consider how evolving knowledge of natural climate cycles plays a key role in understanding modern climate change. The area, being actively uplifted as the crust of the Atlantic Ocean is thrust under the Caribbean, is also a classic study in plate tectonics. The trip is led by geochemist Steven Goldstein, who has done extensive sampling of the reefs for ongoing studies.

BREAKUP OF THE SUPERCONTINENT 3D earth imaging, southern Georgia USA MARCH 8-23/SUMMER 2015

Scientists and students will set off a series of underground explosions and monitor them with hundreds of seismometers in order to image the rocks far below southern Georgia. The basement of the coastal plain was at the center of long-ago events that shaped eastern North America, and researchers want to better understand the continent’s evolution. Some 230 million years ago saw the breakup of Pangaea, the single giant continent comprising most land on earth. Then came one of the greatest volcanic events ever—an outpouring of magma that formed the oceanic rift now separating North America from Europe and Africa. A detailed record of the cataclysms may be preserved beneath Georgia, which started to tear off North America, but in the end, stuck around. This “failed rift” will be investigated by imaging geologic structures in 3-D up to 40 kilometers down, using sound waves. Led by seismologist Donna Shillington, and colleagues at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and the University of Texas, the SUwanee Suture and GA Rift Basin experiment (SUGAR) will dig 100-foot deep holes and set off underground charges in them; these will be recorded by 1,200 portable seismometers deployed by Georgia students along 300-kilometer transects. One set of explosions will take place in March 2014; the next, further east, in summer 2015. Among other things, the project may shed light on the great Triassic-Jurassic extinction, which brought the rise of dinosaurs. The project should also help characterize rocks suitable for future underground storage of industrial carbon dioxide. Fieldwork will involve up to 60 students, and a broad public outreach program. The aims of this study are related to a series of cruises also looking at the breakup of Pangaea, off the U.S. Southeast coast. (see below) Related: SUGAR project website

ONE BILLION YEARS IN DEATH VALLEY Student field trip MARCH 15-22, 2014

California’s Death Valley is the lowest, driest and hottest place in North America, and is rich with geological features that are the target of ongoing research. For the last decade, geologist Nicholas Christie-Blick has been taking undergraduate students here to observe processes written in the rock. Using a teaching style that emphasizes creative interpretation of the students’ own observations, Christie-Blick will have students take stock of the emergence of complex life and ecosystems, the mechanics of crustal deformation, and the varied expression of volcanic eruptions. On a previous expedition, the team discovered that the heavily visited volcanic Ubehebe Crater was active far more recently than thought, and could pose a hazard. Current research is aimed at understanding how earth’s crust is stretching across a series of faults and tilted fault blocks. Assisting this year is graduate student John Templeton, whose work on the structural evolution of the Scandinavian and Scottish Caledonides—a northward continuation of the Appalachians in Europe—is uncovering parallels with Death Valley’s own origins. Related: Volcanic danger found in Death Valley / Web page on Death Valley trip / Slideshow of 2011 Death Valley trip

RISING OCEAN VOLCANOES Cape Verde islands MAR-APRIL 2014 and Madeira/Azores islands JULY or AUG 2014

Unlike most volcanic island systems, the precipitous Cape Verdes, off Africa, are still actively rising. Ricardo Ramalho, a postdoctoral researcher, wants to understand what is at work. Traveling by boat and on land, Ramalho and colleagues will chisel out lava samples from exposed shorelines across the 10-island archipelago to estimate their ages and how far they have moved relative to fluctuating sea levels in the last 2 million years. Among the sampling locations are outcrops described by Charles Darwin on his famous Beagle voyage. Is the oceanic rise that the islands rest upon pushing them up together? Or are magma intrusions shoving them up one by one? On a more practical note, such islands are thought to be tsunami hazards; Ramalho will look at whether a flank collapse of the active 9,300-foot high Fogo volcano caused a huge tsunami 124,000 to 86,000 years ago, washing over nearby Santiago Island and perhaps others. Later in the summer, Ramalho will continue similar work on two other archipelagos, the Madeira and Azores islands, off the coasts of Morocco and Portugal. The rocks will be dated at a U.S. Geological Survey facility in Denver. Related: Project website / Article on Darwin’s link to Cape Verde

SEAFLOOR ORIGINS Ocean drilling, South China Sea, JAN-MAR 2014

On back-to-back cruises of the drilling vessel JOIDES Resolution, the International Ocean Discovery Program will delve into the origins of the South China Sea, and Pacific islands far east of it. The oil-rich South China Sea, one of the most contested marine areas on earth, is also of keen interest to geologists who want to understand how the triangle-shaped basin formed between China, the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam. Scientists will drill cores of basalt near the center and the edge of the sea, to try and pinpoint the forces at work in creating the sea. The basalt is buried under nearly a mile of sediments, so drilling will be a major challenge. Lamont scientist Trevor Williams of the Lamont Borehole Group will direct geophysical measurements made in the holes (and, he is writing a blog). The ship transits Hong Kong to Taiwan. Related: South China Sea cruise webpage / Williams’s expedition blog / Borehole Research Group

UNUSUAL OCEAN CRUST Ocean drilling, Off Guam, Izu, Bonin & Mariana Islands MAR 30-MAY 30, 2014

This string of islands in the Pacific Ocean, extending from Tokyo to the south of Guam, has its origins in volcanic activity triggered by the subduction of the Pacific plate beneath the Philippine Sea. On an International Ocean Discovery Program cruise aboard the JOIDES Resolution, scientists will drill through seafloor sediments to recover tephra produced by the Izu Bonin-Mariana oceanic island arc over the last 50 million years. The crust in this area is thicker than normal—20 to 23 kilometers. And unlike most crust formed from mantle rock below, it contains a middle layer rich in silica. Geochemist Susanne Straub and colleagues are investigating why it is so atypical. The new samples may finally explain whether the silicic crust formed at the onset of subduction or grew gradually through time. Lamont scientist Gilles Guèrin will direct downhole logging operations aboard the ship. Departs from Keelung, Taiwan and arrives at Yokohama, Japan. Two related IODP cruises will follow through October, with Laureen Drab and Sally Morgan of the Borehole Research Group directing downhole logging operations. Related: Project website / Borehole Research Group

FRACKING RISKS Air pollution, groundwater tests, northeast Pennsylvania APRIL thru EARLY SUMMER 2014

The national boom in hydraulic fracturing has raised concerns about the effects on groundwater and now, potentially, air. Earth Institute researchers have tested groundwater in heavily fracked areas of northeastern Pennsylvania since last year, and this spring, will begin an air-monitoring program in nearby homes and outdoor areas. Recent reports suggest that volatile chemicals used in fracking can reach the air during drilling and production; there are also concerns about diesel engines, flaring of excess gas, and release of natural underground radioactive elements. Geochemists Beizhan Yan and Steven Chillrud will use portable and stationary air monitors (some of which they developed themselves) to measure individuals’ exposure levels to volatiles, soot, silicon, metals and other substances in 10 to 15 homes in adjoining Susquehanna and Bradford counties, Pennsylvania. The team will also continue monitoring of groundwater near wells. Done in collaboration with the University of Pennsylvania. Related: Fracking and air pollution / Earth Institute fracking experts / Center for Public Integrity investigates fracking and air pollution

ON THE TORNADO TRAIL Storm chasing, U.S. High Plains LATE MAY-EARLY JUNE 2014

Extreme-weather researcher John Allen spends much time analyzing computer data, in pursuit of ways to better forecast tornadoes and other destructive storms. But he also pursues the real thing. During the spring tornado season in the U.S. High Plains, Allen, a postdoctoral researcher at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society, makes periodic storm-chasing trips to observe storms up close. Migrating by car in a route he expects to include western Kansas, eastern Colorado, the Nebraska panhandle, southeastern Wyoming and southwestern South Dakota, he hunts for incipient storms. Each day on the road, he tries to predict where they might brew, using computer models, satellite imagery, synoptic charts and his own observations of the weather. Then he heads to the most likely spots (while trying to keep a safe distance, and carefully planning escape routes). Currently, scientists can give far less warning of tornadoes than of hurricanes; generally, only a few days for precursor conditions, and only hours to minutes for actual tornadoes. Allen and his colleagues would like to extend reliable forecasts of tornado-prone periods out to a month, to help endangered areas take precautions. They also want to know what effects changing climate might have on the frequency and strength of tornadoes and other storms. Recently, Allen’s colleagues have had some preliminary success in extended-range forecasting, but the models are still being tested. Allen had one close call last year, when he witnessed the widest tornado ever recorded, near El Reno, Okla., on May 31, 2013. The tornado killed eight people, including four storm chasers. Related: Earth Institute research on tornadoes / Allen’s account of the El Reno tornado

ARCTIC ICE: A DRONE’S-EYE VIEW Test flights, Yakima, Wash. APRIL-MAY, AUG 2014. Field deployment, Svalbard, Norway MAR 2015

Taking a page from the military, scientists are starting to use aerial drones to view remote parts of the world. To better understand the complexities of what is driving fast-melting Arctic sea ice, oceanographer Chris Zappa and colleagues have developed instruments that can fly on drones the size of a ski bag for up to 10 hours. These can go into places impractical for ships, and too distant for satellites to get a detailed view. This spring, they will first do test flights over arid terrain at the Army Training Center near Yakima, Wash. Instruments will produce visible, near-infrared, and thermal infrared hyperspectral images; high-resolution topographic maps using lasers; and measurements of atmospheric gases. An ice-penetrating microwave radar Zappa and colleagues are developing should also reveal how old and thick sea ice is, the dynamics of how it is melting, and eventually, even how waves are influencing the process. The team is also developing buoys with instruments that the drones can drop into the ocean. The drones will be initially deployed near the Arctic research station in Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard, Norway, in March 2015. The study, involving NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is part of an international collaboration to study the ocean, ice, and atmospheric processes between Greenland and Norway. At Svalbard, researchers will travel by snowmobile,each with a rifle to guard against polar bears. (In a separate project, marine geologist Alessio Rovere is using camera-equipped drones to study coastal erosion in Italy and elsewhere.) Related: NYT article about scientific use of drones / Article on drones to study coastal erosion

REDUCING ASIAN ARSENIC Well testing, investigations of human exposure, Bangladesh, India JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2015 and ONGOING

Naturally occurring arsenic in groundwater has been found in 70-some countries including the United States, and is a particular problem in South Asia, where it may be slowly poisoning as many as 100 million people; in Bangladesh alone, it may be causing 1 in 5 deaths. In a series of projects across Bangladesh, India, Vietnam and newly opened Myanmar, geochemist Alexander van Geen and colleagues are analyzing how arsenic gets into water, and developing innovative ways to address the problem. These investigations are part of a larger arsenic program involving the Mailman School of Public Health and other parts of Columbia, which includes large-scale studies on arsenic effects, dedicated arsenic clinics in Bangladesh, and community outreach in central Maine, one of many other places that suffer contamination. In some sites, van Geen’s team continues to develop an understanding of the geologic forces that drive contamination by drilling into aquifers and analyzing sediments and movements of water. The group is also expanding testing for the tens of millions of existing wells across south Asia. Most people are within walking distance of a low-arsenic well, yet few know whether their own is polluted. and large numbers are still using polluted water. One recent program seeks to subsidize such tests. In the northern Indian state of Bihar, van Geen has found that villagers are willing to pay 20 rupees (about 40 cents) to have their well tested program. Van Geen and colleagues frequently travel to a study site just east of the Bangladesh capital of Dhaka, to continue well testing, as well as trials of new technique to measure arsenic exposure in individuals. In conjunction with the University of Chicago, the program runs a clinic for potentially affected villagers in this area, which is tracking health effects. In 2015, the program will start up a new phase, in which expanded well testing will be done near the cities of Calcutta, Yangon and Hanoi, to help determine how pumping of groundwater for irrigation might be mobilizing arsenic; a related project in Bangladesh will look at ways to mitigate such effects. The team also works in Maine, and, next summer, in Illinois. (see below). Related: Columbia’s arsenic research / Arsenic pollution near Hanoi / van Geen’s work in southeast Asia

ARSENIC IN AMERICAN DRINKING WATER Drilling, visit by Asian scientists, Bloomington/Peoria, Ill. MAY or JUNE 2015; Well testing, community outreach, central Maine ONGOING

In scattered places across the US, arsenic seeps naturally into well water–for instance in central Illinois, where some 40 public groundwater supplies contain naturally occurring arsenic, and must be filtered. The poison comes from sediments deposited at the end of the last ice age, but the exact details of how it gets into water are not known. To better understand the geologic forces at work, a team led by Lamont-Doherty geochemist Alexander van Geen and Tom Holm of the Illinois State Water Survey will collect sediment cores from the Glasford and Mahomet aquifers, near Bloomington and Peoria, using newly refined techniques. Up to five holes will be drilled to a depth of 300 feet. The scientists will test a new sampler that can retrieve water and sand at the same time, to improve accuracy of their results; samples will be processed on site with a mobile geomicrobiology lab. Arsenic is a much greater problem in aquifers of South Asia where van Geen usually works, and the team will host 16 observing scientists and grad students from Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Myanmar and other countries for the two-week coring project. The scientists will analyze samples on the spot, and if the new techniques work, hope to export them to Asia. The team also continues ongoing water-testing and community-outreach work in central Maine, where arsenic has been detected in many wells. As an offshoot, the researchers recently also found excess amounts of naturally occurring radioactive uranium or radon in wells, which could affect as many as 400,000 people in the state. Research into this phenomenon is ongoing. Related: Columbia’s arsenic research

ORIGINS (AND HAZARDS) OF THE U.S. EAST COAST Subseafloor imaging, U.S. Southeast APRIL 1-16, MAY, SEPT 2014 and APRIL 2015

Along the U.S. east coast, a team is looking into both long-term geologic history and the potential for modern earthquakes and tsunamis. Some 200 million years ago, the supercontinent of Pangaea was splitting apart, and the Atlantic Ocean opened. Scientists are unsure whether the rift came from massive volcanism, or stress along old faults and weak zones in pre-existing rocks: but they do know that volcanic rocks from the time undergird much of the coast, and faults and weak zones are scattered about. The faults can come alive; a magnitude 7.3 earthquake destroyed much of Charleston, S.C. in 1886, and in 2011, a M 5.8 in Virginia rattled much of the eastern seaboard. To map the structure and history of the rift margin, researchers will use energy waves generated on land and sea. In April, a team led by seismologist James Gaherty will embark on the R/V Endeavor to place 30 seismometers on the seafloor off North Carolina, to record small earthquakes over the next year; these will generate ultrasound-like images of earth’s mantle. In May, they will deploy seismometers on Cape Hatteras for the same purpose. Then, in four cruises in September-October led by seismologist Donna Shillington and colleagues, the Lamont-operated R/V Langseth will send pulses of sound down to generate pictures of the uppermost mantle, the crust (including faults), and overlying sediments. The scientists will retrieve both land and sea seismometers in April 2015. In addition to looking for hidden faults, the scientists are interested in steep slopes off Virginia and North Carolina where cubic miles of sediment, perhaps jarred by quakes, have slid down in past ages. Such submarine landslides can generate tsunamis (such as one in 1927 off Newfoundland), and the project aims to better understand the threat. Other institutions involved: the University of Texas, University of Memphis, Rice University, Southern Methodist University, Yale, Woods Hold Oceanographic Institution and The College of New Jersey. This project is related to a land-based seismic study in Georgia this spring, also looking at the breakup of Pangaea (see above). Related: Project website / Study of East Coast submarine slides / The 1886 Charleston quake

NEW TOOLS TO SURVEY POLAR ICE Test flights, upstate New York MARCH/APRIL; Greenland JULY or AUG; Antarctica NOV 2014

In recent years, Lamont-Doherty scientists and engineers have played key roles in dedicated NASA-sponsored aerial geophysical survey flights to create 3D maps of changes in the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets. Now, they have designed a suite of instruments that can be flown on routine supply flights to polar bases, greatly expanding chances to collect data. The so-called IcePod fits on a turboprop LC-130, workhorse of the Air National Guard fleet that supplies bases. It contains radars that measure the tops of ice sheets, their deep interiors, and water lubricating their beds. Lasers measure surface elevations and snow textures, as well as reflectivity and temperature. IcePod receives tests out of Schenectady, N.Y., in March-April. Tests will continue over land and sea out of Kangerlussuaq, southwest Greenland in May/June; and in Antarctica in November. Contact: Margie Turrin. Related: IcePod website / Story on IcePod / Guardian video coverage / Tests over upstate New York

EVOLUTION AND CLIMATE ON THE HIGH PLAINS Excavations, paleoenvironment studies, southwest Kansas MAY 2014

Paleoenvironment researcher Pratigya Polissar and postdoctoral researcher Kevin Uno will head with colleagues to the fossil-rich Meade Basin in southwestern Kansas, to study biota past and present. Here at the edge of the High Plains, in rocks spanning 5 million years, they will try to understand what drove the evolution of small mammals such as the wood rat and grasshopper mouse. Did they develop mainly from competition among themselves, or did changes in climate and ecosystem play a decisive role? To get at the influence of climate, Polissar and Uno will isolate ancient leaf waxes from river sediments and floodplain deposits. From isotopic fingerprints in the wax, they can reconstruct the basin’s past vegetation, and how hot and dry or cold and wet the region was. Camping at a state park near a ranch where fieldwork will take place, Uno and Polissar will dig into outcrops to get fresh, unweathered sediments. Other team members will collect calcium carbonate nodules for use in estimating past temperatures. Bob Martin, a paleontologist at Murray State University, will lead a search for small-rodent fossils using water and sieves to shake loose teeth and bones. The team will also trap and release modern rodents to collect hair samples for comparative analysis in the lab.

DIVING INTO THE LOST WORLD OF THE MAYA Underwater excavations, tree-ring studies, western Belize MAY 1-15, 2014

The lowlands of Belize, Guatemala and Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula hold some of the most mysterious features on earth: vast water-filled cave systems pricked at the surface by thousands of small lakes and cenotes—caverns with collapsed roofs, which lead to the depths below. The now-vanished Maya civilization held them sacred as entries to the underworld, and many contain offerings including carvings and human bones. The cenotes also preserve the remains of ancient animals, trees and other objects that have fallen in. In this expedition, tree-ring scientist and diver Brendan Buckley will join efforts to explore a 6-mile-long string of 25 cenotes and lakes at Cara Blanca, in forested western Belize. Past expeditions led by University of Illinois archeologist Lisa Lucero have shown that some pools here, as deep as 200 feet, were used as shrines. In addition to artifacts, they hold bones of giant sloths, mastodons and other animals, which may shed light on evolution and past climates. Buckley will study the many large trees that have fallen in, and been extraordinarily preserved in the anoxic waters. Such old trees may help date archeological deposits, but more importantly, their rings may hold climate records going back many centuries before any trees now on the surface. These might shed light on why the Maya civilization disappeared, and other questions. Buckley and technical divers will attempt to saw sections of large trunks underwater. Following this, Buckley will continue west through the highlands of Belize, where he hopes to search for possibly very old living conifers in remote forests, which may also hold long-term climate records. Related: Buckley’s work on ancient southeast Asia / Lucero’s Cara Blanca blog / Video of dives / USA Today article on Cara Blanca

CHANGING NORTHEAST FORESTS Tree coring, Maine, Massachusetts, northern New York APRIL-AUG 2014

Scientists suspect that changing climate is affecting the health and composition of northeastern U.S. forests, but the results may so far be subtle. In an effort to understand how trees may react to shifting climate, interdisciplinary teams from a dozen institutions are working to reconstruct the history of forests over the past 2,000 years both here and in Alaska, where climate effects on forests are already easily visible. As part of the project, called the Paleo-Ecological Observatory Network, tree-ring scientist Neil Pederson and colleagues are coring old trees across the northeast to chart changes in growth, species composition and occurrence of fires. In April or May, they will work at northern New York’s Goose Egg state forest, near Vermont, where some oaks and hemlocks date back 300 years or more. Later in the season, they move to Harvard Forest in central Massachusetts, and Howland Forest in central Maine. Both have been heavily studied in recent decades by scientists observing carbon uptake, nutrient uptake and other factors. Pederson’s studies have already shown that huge droughts have hit the region in past warm times, and that the last 100 years have been extraordinarily wet. Work with the team will require short to medium hikes. Related: PalEON website / Lamont PalEON page / Tree rings show past eastern droughts

TALKING OCEAN BACTERIA Shipboard experiments, off Barbados/Bermuda MAY 1-30, 2014

Trichodesmium, known as sea sawdust for its yellowish blooms, is a colonial cyanobacterium that plays a key role in nutrient-poor waters by fixing carbon dioxide and nitrogen into forms that other marine life can use. Microbial oceanographer Sonya Dyhrman and her team will try to understand what makes them tick, on a month-long cruise aboard the research ship R/V Atlantic Explorer. Scientists used to think that phosphorus chemistry controlled where and how Tricho lives in the western North Atlantic, but the recent discovery of other bacteria living on Tricho colonies has complicated the picture. These so-called epibionts produce molecules called AHLs that allow them to “talk” to each other and change the way they process phosphorus. But are Tricho in on the conversation, too? In the low-phosphorus waters between Bermuda and Barbados, the team will collect Tricho and force the epibionts to communicate by adding AHL. They hope to see which cells are talking to each other, what forms of phosphorus are being used, and how nitrogen fixation rates vary—key questions for how the base of the food chain works. Back in her lab, Dyhrman will continue the analyses, including DNA sequencing to examine the genetic basis of bacterial communication in the ocean. Related: Dyhrman’s work on other key ocean microbes

PLUMBING DEEP CURRENTS North Atlantic cruise, MAY 2014

Scientists have an intense interest in the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, a circular current that transports heat north from the equator and helps control climate. This cruise is part of the 10-year Line W project, which studies the warm surface water as it dives deep and flows back toward the equator. Researchers from several institutions, including geochemist William Smethie, will sail along the continental slope south of Cape Cod across the Gulf Stream and the deep western boundary current, to recover data from moorings that take daily vertical profiles of temperature and salinity; they will also stop to take samples for other parameters including small amounts of manmade chemicals that act as tracers of where water masses originated. Chief scientist is John Toole of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution; cruise departs Woods Hole, Mass. aboard the R/V Knorr. Related: Line W website

HIGH IMPACT Search for meteorite craters, western Russia MAY 9-23, 2014

Last year’s destructive meteor explosion over Russia was a wake-up call that large extraterrestrial impacts may be more common that previously thought. Only about 170 meteorite craters have been positively identified on earth, but due to the difficulty of finding them, there may be many more unrecognized. Geophysicist/geologist Dallas Abbott travels the world looking for hidden craters. This spring she will continue work begun last year, when she traveled with Russian colleagues near the city of Nizhny Novgorod to several unusually deep elliptical lakes with raised rims identified as possible candidates. The team surveyed topography, combed the ground with metal detectors and took soil samples, in search of possible fragments of a meteorite or other signs of what could have created the lakes. The team found some clues, but nothing positive; they will continue working in more detail this time. Related: Atlantic article on Abbott’s work / NY Times article on Abbott’s research off east Africa / LiveScience article on Abbott’s Halley’s comet hypothesis

BUSHMEAT Studies of for-profit wildlife hunters, Laos, Gabon, Cameroon, Congo SUMMER 2014/ONGOING

Hunting has long been an important source of food for people in tropical forests of Asia, Africa and Latin America. But in recent years, “bushmeat” has also increasingly become a commodity for sale, leading to unsustainable levels of harvesting. This in turn may be affecting forest ecosystems–not just animal populations, but seed dispersal and vegetation. Miguel Pinedo-Vasquez of the Earth Institute Center for Environmental Sustainability is the scientific coordinator for a global team exploring how communities hunt and use bush meat in the Amazon, Congo and Mekong River basins. The project, under the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), is in its first year of fieldwork. Researchers will travel to Laos this summer to investigate harvesting of bushmeat for medicinal markets in China, including a range of animals from rhino to pangolins to snails. Others are investigating bushmeat markets in Gabon, Cameroon and the Congo. The multi-year program aims to develop management tools to improve the sustainability of harvesting. Related: CIFOR information on bushmeat

TUNDRA CLIMATE CHANGE Ecology surveys, north Alaska MAY-JULY 2014

Ecologist Natalie Boelman is leading a five-year project to study how warming climate may influence life on the Alaskan tundra. As climate warms, it appears that shrubs are taking over, potentially affecting existing vegetation and the life cycles of insects and migrant birds that breed here. Starting mid-May, as snow is melting, researchers working from Toolik Lake research station will set up to study the behavior, physiology and interactions of various species. Boelman’s part is a network of microphones that record abundance of songbirds via their calls. Also, in a related project, researchers will bring a land-based LIDAR (Light detection and ranging) system to the tundra, enabling them to measure subtle changes in plant cover undetectable in satellite images. Plant physiologist Kevin Griffin should be there in mid-July to perform a 3-week experiment to measure the carbon-dioxide flux from a small plot of vegetation with instruments—part of his long-term research at Toolik to study plant responses to CO2, temperature and soil nutrients. Related: Project website / Q&A with Boelman / Boelman’s 2011 field blog / Griffin speaks on how climate may be changing trees and plants

DARK UNDERBELLY OF AN ICE SHEET Seismometer deployments, northern Greenland JUNE 2014

The rapidly melting Greenland ice sheet—a potential wild card in future sea-level rise—is being intensively studied via satellites and, increasingly, ice-penetrating geophysical instruments. However, scientists know almost nothing about the actual rock base on which the sheet rests—a missing factor that could drastically affect calculations about its current and future behavior. Scientists are working to plant a new network of seismic instruments across the ice sheet, aimed at imaging the rocks far below. The first came fully on line in 2013; this year, a team led by seismologist Meredith Nettles will expand the network, mostly in the far northern regions. Working from the Summit scientific station at the very top of the sheet, Nettles and a grad student will travel daily by Twin Otter airplane, to land and plant stations at a half-dozen far-flung locations. Among the mysteries they and colleagues hope to investigate: an apparent giant volcanic caldera in the north whose heat may be hastening melting of the ice sheet from below. No one knows the extent of this volcanism, or how long it has been active. The scientists should also get a clearer picture of how the crust and the mantle beneath it have evolved over long periods. This in turn should help scientists understand whether the rocks that make up Greenland have been sinking or rising over time, and how that might skew current satellite measurements of the ice sheet’s shifting elevations, and thus predictions of sea-level rise. Nettles has already done other pioneering work in Greenland, including the discovery of glacial earthquakes, generated by rapid movements, as ice falls into the sea. Related: Glacial earthquakes / Greenland Ice Sheet Monitoring Network

HOW FORESTS REGROW Studies of tree communities, northeast Puerto Rico JUNE-JULY 2014

Half or more of the world’s tropical and subtropical forests are indirect products of human disturbance—regrown after cultivation, logging or fires have razed trees. Forest ecologist Maria Uriarte seeks to understand the dynamics of second-growth forests, which have important implications for biodiversity, climate and water resources, but which scientists have neglected compared to mature “natural” forests. Uriarte and her students and collaborators have been working in Luquillo Experimental Forest in northeast Puerto Rico, where scientists from many disciplines from hydrology to herpetology have been working for decades in the same area on long-term ecological research projects. Luquillo is in some ways typical of many places in Puerto Rico, which was almost completely deforested 50 years ago, but is now once again 60 percent covered with trees. Among other things, the team is documenting which tree species are growing, how fast they build biomass, and how different kinds of trees react to weather patterns and other factors. The work involves clambering over hilly, densely vegetated terrain to census trees and install instruments to measure growth. The findings may be especially important in studies of global climate change, as assumptions about how trees take up carbon in more mature forests may not play out in these understudied secondary ones. Uriarte is also working on related studies at the La Selva research station in the central lowlands of Costa Rica. Related: Uriarte research pages / Luquillo Long Term Ecological Research

EAST AFRICA RIFTING Seismology, geology: Malawi, Tanzania, Botswana MARCH, LATE JUNE-JULY 2014 and FALL 2014

In 2009, a series of earthquakes shook northern Malawi, leaving thousands homeless—a reminder that the region sits atop the 2,400-mile long East Africa Rift, along which the continent has been tearing apart for 25 million years. The process is slow, but the buildup of strain and upwelling of magma associated with it has created a string of volcanoes and quake zones that threaten millions. An interdisciplinary team of Americans and Africans is studying the rift’s long-term evolution, and its real-time hazards. In 2012-13, a team led by Lamont scientists Donna Shillington and James Gaherty deployed seismometers and GPS instruments across northern Malawi and neighboring southern Tanzania to measure the subtle spreading motion, while geochemist Cornelia Class and Tanzanian colleagues collected lava samples. Working with the national geologic surveys and universities, the team is training Malawian and Tanzanian scientists and technicians, and working to increase public awareness in villages. In March 2014, team members will revisit instrument sites and download data. A larger deployment of some 40 seismometers and other research is planned for June, in Malawi and Tanzania; this will involve multiple teams of researchers, and possible electrical and magnetic measurements to image geologic structures far below the surface. In a separate but related project, in the fall, geophysicist Roger Buck will participate in a study of the rift system’s southwest terminus, in Botswana’s Okavango Delta region. Deployed by helicopter, they will look for evidence of a magma intrusion that Buck believes is there by setting off small explosions and measuring the echoes with seismic instruments. (The Botswana trip is led by Juan Pablo Canales of Woods Hole Oceanographic; Buck will lead helicopter deployment of stations. Related: Researchers’ blog from Malawi

PAST AND FUTURE WEST COAST RAIN Sampling of old lakebeds, California/Oregon MAY/JUNE/AUG 2014

The ongoing drought in California raises serious questions about the sustainability of water supplies for this region. There is a pressing need to understand how this drought fits with past climate patterns, and whether current or future drying may be associated with global warming. Since last year, researchers have been working to plot past rainfall at northern California’s saltwater Mono Lake, whose basin is an important water source for Los Angeles. This year they are expanding to other largely dried-up lakes. To plot Mono’s level back as far as 27,000 years, PhD. candidate Guleed Ali and geochemist Sidney Hemming have sampled deep layers of sediments far above the current shoreline (it reached its high stand 15,000 years ago, and has fluctuated widely since). In May, they go to the western side of the Great Basin, to sample now mostly dry Owens Lake, whose drainage also is tapped by LA. In June, they investigate the vestiges of Lake Lahontan, which once extended through Oregon, California and Nevada, near what is now Summer Lake, Ore.; and in August, the dried remains of Oregon’s Lake Chewaucan (now shrunk to much smaller Abert Lake, also in Oregon). On foot, Hemming and Ali will map sediments and remove samples by hand. In the lab, new techniques will enable them to date layers far more accurately than in the past. By this, they hope to understand whether lakes at the same latitude dried out simultaneously, possibly due to changes in the jet stream. Also this field season, glacial geologist Aaron Putnam will sample glacial moraines in the same areas and use surface exposure dating techniques to provide further context. Related: Watch a video and read a story about the project

TROPICAL SUMMITS AND THE LAST ICE AGE Glacial debris sampling, Costa Rica JUNE 1-20, 2014

Many tropical mountains have the same shape; from Costa Rica to East Africa, Papua New Guinea and Taiwan, steep slopes are often capped by relatively flat summits. Graduate student Maxwell Cunningham and scientists Colin Stark and Mike Kaplan want to know if mountain glaciers during the last ice age helped to sculpt these summits. To help answer the question, the researchers will trek to the top of Costa Rica’s highest peak, 12,000-foot Mount Chirripó. Camped near the summit, where temperatures plunge to freezing at night, and days are often hot and damp, they plan to map the landscape on foot (frequent cloud cover over Chirripó has made satellite imaging difficult). They also hope to collect rock samples and landslide debris that would have been left exposed as climate warmed and glaciers retreated, perhaps 15,000 years ago. Using geochemical dating techniques in the lab, they will try to establish whether Chirripó lost its ice at the same time as other peaks in the tropics, and whether erosion was greatest during the coldest times, or hastened as thawing set in.

EXPLORING A MEGA-QUAKE ZONE Seismic studies, U.S. Pacific Northwest JUNE 22-JULY 27, 2014

Off the coasts of Oregon, Washington and British Columbia, seafloor earthquakes have produced giant tsunamis like the one that hit Japan in 2011. The last struck more than 300 years ago, and the region may be due for a repeat. A multi-institution experiment, the Cascadia Initiative, will help assess the risk by illuminating the subduction processes related to the Juan De Fuca and Gorda plates, which are sliding beneath North America. Aboard the R/V Thompson, marine geophysicists Maya Tolstoy, Andrew Barclay and colleagues will use the remotely operated underwater vehicle Jason to collect ocean-bottom seismometers that in 2013 were left on the seafloor to record small earthquakes there. The seismometers have been specially designed by Lamont-Doherty engineers to resist damage inflicted by fishing trawlers on similar instruments in the past. The data they have recorded should help researchers illuminate tectonic processes and better understand the stresses building up along the subduction zone. Related: Cascadia Initiative website / Student blog from last Cascadia expedition / Ocean Bottom Seismograph Instrument Pool / Cascadia Initiative / Story in Nature

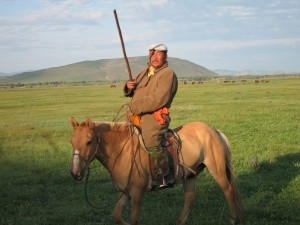

GENGHIS KHAN’S RISE Climate studies, central Mongolia JUNE 2014

In the 13th century the Mongols, led by Genghis Khan and his descendants, built history’s largest contiguous empire, reaching from the Pacific Ocean to eastern Europe. How did nomadic horsemen from a cold, arid and supposedly uncivilized steppe accomplish this? The 2010 discovery of long-dead ancient trees near the empire’s seat suggests a partial reason. Tree rings going back to around 300 AD—now the longest climate record for this part of the world–suggest the Mongols rose amid unprecedented rain and warmth that turned grasslands lush, enabling them to raise the vast numbers of horses and other livestock needed for expansion. In a project now in its third field season, an interdisciplinary team of Americans and Mongolians is testing this idea. Leaders are tree-ring scientists Neil Pederson (Lamont-Doherty) and Amy Hessl (W. Va. University). This year, graduate student Cari Leland will search for older tree-ring specimens. University of Washington’s Avery Shinneman will collect sediment samples from lakes to look for signs of past livestock populations. A workshop with Mongolian scientists in Ulan Bataar will precede the field-season. Related: Video, photo gallery and story on the project / Mongolian Climate, Ecology & Culture blog / Science magazine article on the project / Economist article on the project

DATING EARLY HUMANS Rock sampling, Greece, northwest Bulgaria LATE JULY 2014

When did early human ancestors first enter Europe? Geologist Dennis Kent is working with colleagues to try and resolve the question by dating fossils not of people themselves, but of animals that probably migrated with them. Along with stratigrapher Giovanni Muttoni of the University of Milan and others, Kent will visit sites in Bulgaria and the Peloponnesian peninsula of Greece that hold the remains of elephants thought to have migrated from Africa around the same time. They hope to date the layers associated with these fossils by drilling out rock samples that will allow them to map out periodic reversals in earth’s magnetic field, which are stored in the rocks. The Bulgarian fossil site is within a cave; the one in Greece is a quarry. Bulgarian and Greek experts in the local geology will work with Kent and Muttoni. Some specialists argue that proto-humans arrived as long ago as 1.8 million years; Kent believes it was much later, maybe 850,000 years. The scarcity of human fossils and the challenge of accurately dating anything from that long ago have left this a matter of controversy, but the paleomagnetics study holds promise for clarifying the question. Related: Read about Kent’s work to date the earliest tools

WHERE ICE MEETS OCEAN Seawater studies at glacial fronts, Northwest Greenland JULY 15-30, 2014

Greenland’s vast and rapidly waning glaciers, now contributing up a quarter ongoing sea-level rise, are tracked mainly through satellite images, This study brings researchers to the edge of the ice as it juts into the sea, to take water measurements that should shed light on how ocean temperatures and currents around the ice may be causing some glaciers to surge faster than others. Lamont postdoctoral scientist David Porter will work from a tiny fishing village in the Upernavik Islands with local people to take profiles of water at different depths at the front of Alison glacier, which is actively surging forward and calving icebergs into the sea. The work is done in small fishing boats; locals will be trained to continue to the work over the long term. Related: Expedition blog

CLIMATE AND AFRICAN EVOLUTION Excavations of early human times, southern Ethiopia JULY 2014

The hot, arid Turkana Basin of southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya has long been a key region for scientists studying the evolution of early humans and other species. Rock formations are rich with the remains of extinct hippos, pigs, elephants, gazelles, buffalo and monkeys, and are the source of some of the most famous human-ancestor fossils, earlier excavated by the Leakey family. They also contain a remarkable record of past climates. Postdoctoral researcher Kevin Uno and a team of international scientists are looking at changes in vegetation and rainfall in this region from 3.6 million to 1.1 million years ago, and how they may have led to the rise and fall of these various ancient inhabitants. With the aid of a pickaxe, Uno will collect sediments containing leaf waxes from ancient plants. He and his colleagues will camp well above the Omo River (to evade mosquitos and crocodiles), and use an off-road vehicle to explore sites. When analyzed, the plant waxes should reveal the extent to which trees or grasslands covered the landscape. They may also indicate whether shifts in wind and rainfall patterns led to changes in vegetation that may have influenced how species evolved. Led by French paleontologist Jean-Renaud Boisserie, the team will of course be looking for fossils—large mammals, crocodiles, fish, turtles, and if they’re lucky, proto-humans. Seasonal rains each year usually expose new, potentially rich layers. Related: Story on Uno’s work to help track illegal ivory

PRESERVING VIETNAM’S HIGHLAND FORESTS Tree physiology studies, trail development, international meeting. Bidoup Nui Ba National Park LATE JULY/EARLY AUG 2014, NOVEMBER 19-22, 2014, and JANUARY 2015

Among other treasures, Vietnam’s highland forests hold some of Asia’s largest, oldest trees—survivors of 1,000 years and more, which have provided scientists with eye-opening keys to climates and civilizations of the past. These forests are under intense pressure from loggers, farmers, hunters and plant foragers. Tree-ring researcher Brendan Buckley has been working here for years, particularly in Bidoup Nui Ba National Park, near the picturesque city of Dalat. In efforts to preserve the park, Vietnamese officials and foreign funders including the Japanese are encouraging expanded research and eco-tourism. As part of this, Buckley is helping develop a trail system that will allow a limited number of hikers to see the ancient trees and other parts of the forest. Locals are being hired as rangers and guides, and students from Vietnamese higher-education institutions are being involved in related field research. This includes a new project to study trees’ long-term responses to drought, and the physiological mechanisms that help them adapt, or not. During the summer, researchers will study a 1-hectare research plot containing 60-some tree species, recording specific data such as leaf thickness, taking DNA samples, and measuring stable isotopes in leaves and wood that will reveal how trees cope with changing weather. This portion will involve Buckley, dendrochronologists Dario Martin-Benito and Laia Andreu Hayles, and forest ecologist Maria Uriarte. In late July and early August, Buckley and tree physiologist Kevin Griffin will lead the first of a series of annual field schools, geared for international undergraduate and graduate students. Students and instructors will camp in the forest and participate in studying long-term ecological plots. In November at the park, Buckley and colleagues will convene an international meeting of scientists studying many aspects of the southeast Asia highlands including plants, trees amphibians and primates. Buckley and colleagues recently found tree-ring evidence that the fall of southeast Asia’s ancient Angkor civilization may have been hastened by drought. Buckley is based part of the year in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and studies tree rings in surrounding nations. Related: Tree Ring Lab web pages / Audio slideshow on work at Bidoup Nui Ba / The Asian drought atlas / Study on the fall of Cambodia’s Angkor Wat / Log coffins of an unknown civilization

DATING HUMANITY’S DISTANT PAST Geologic fieldwork, northern Kenya AUG 2014 (As of 6/20/2014 postponed to 2015))

Some of the most important fossils and artifacts related to human ancestry come from the dry, remote region around northern Kenya’s Lake Turkana, dug by the Leakey family and others. But accurate dating here—the key to understanding the remains—remains a continuing challenge. Lamont-Doherty geologists Dennis Kent and Christopher Lepre are working with paleontologists to date finds using advanced techniques that track periodic reversals in earth’s magnetic field recorded in rock layers. Lepre is working on the northern shores with a French team to collect and date sedimentary rocks related to ongoing excavations. Kent will concentrate further south, near the village of Loiyangalani, drilling out samples of volcanic rock. In 2011, Lepre and Kent used paleomagnetism to date the earliest sophisticated tools yet found—1.8 million years, 300,000 years earlier than previously thought. Now, they hope to probe the deeper past—3.5 million to 4 million years ago, when the human precursor Australopithecus is thought to have lived. The Turkana region, inaccessible by road, is important for wildlife as well as paleontology. Related: Read about dating of the earliest tools

UNTANGLING NORTHERN HEMISPHERE WEATHER CYCLES Tree-ring collections, Russian far east JULY 2014

The Pacific Decadal Oscillation, a cycle that every few decades suddenly changes sea-surface temperatures from Japan and Russia across to Alaska and Canada, deeply affects fisheries and other human endeavors. Its causes are a cipher. In an effort to understand it, tree-ring researchers will make a collecting trip to Sakhalin Island, off the coast of Siberia, where they hope to extract weather records going back 1,000 years. Combined with existing tree-ring chronologies from Alaska, the records should shed light on how consistent the cycle is, and whether it is connected to other known cycles, including more short-lived shifts caused by the El Nino-Southern Oscillation of the tropics. Future trips are aimed at other rarely visited areas including the Sikhote-Alin mountains of the far eastern Russian mainland, and the Kuril Islands, north of Japan. Tree-ring scientist Rosanne D’Arrigo along with Olga Solomina of the Russian Academy of Sciences will lead. Related: Web page on the Pacific Decadal Oscillation

THREATS TO HIMALAYAN ICE AND RIVERS Hydrology, geology, tree rings, Bhutan LATE SUMMER/EARLY FALL 2014

Many Himalayan glaciers are melting, potentially endangering water supplies and hydropower for 1.3 billion people downstream. Closer to the icy peaks, big meltwater lakes are building behind leaky natural dams that sometimes burst and kill people downstream. A new interdisciplinary project seeks to better predict future glacial dynamics and water flow in Bhutan, and to manage the results. A team including Summer Rupper of the University of Utah is studying dynamics of the glaciers. A team led by Lamont geochemist Joerg Schaefer is studying rocks and landforms around glaciers to determine past climate conditions that have led to advances and retreats. This will be collated with samples of tree rings taken by Lamont dendrochronologist Edward Cook and colleagues at lower elevations. Fieldwork in 2012 and 2013 done by Rupper and glacial geologist Aaron Putnam around the remote Raphstreng Glacier included placing of stakes on the ice to measure melt or growth; these will probably be revisited in 2014. Participants should expect difficult conditions; access to the Raphstreng involves a week or more of high-elevation trekking each way, and probable bad weather. Related: New York Times blog from the 2012 expedition / Read an article about the project / Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness conference

AMAZONIA BURNING Land use studies, eastern Peru AUGUST 2014

For millennia, people across much of Africa, Asia and South America have set fires to clear land for cultivation, pastures or hunting. This common practice is becoming problematic as growing population, fragmentation of forests and warming climate lead to ever larger, more destructive escaped fires. In the fast-developing Ucayali River region of the Peruvian Amazon, an interdisciplinary team is studying how fire is used, and how it is contained, or not. During August-September “burning season,” they have chased down fires in real time using both satellite images and reconnaissance into the back country. They have measured fires’ extent and qualities, mapped surrounding infrastructure and plant communities, and collected data from local farmers. This is the last year of the five-year project. Based at the Earth Institute Center for Environmental Sustainability. Team is led by Miguel Pinedo-Vasquez. Related: Watch a documentary on the project / Read about the global fire issue / Fires in Western Amazon website

MONITORING CORAL VITAL SIGNS Palmyra atoll AUG 15-SEPT 15, 2014; Florida Keys, Puerto Rico ONGOING

Geochemist Wade McGillis will travel to the tiny Pacific atoll of Palmyra, part of the Line Islands, some 1,000 miles south of Hawaii, to investigate the connections between climate and coral health. Palmyra, built largely of corals both living and dead, is in one of the world’s most pristine marine regions, and is home to a small U.S. research station. Fossil corals, some 6,000 years old, have attracted researchers interested in extracting records of past natural climate shifts. Others, like McGillis, are interested in the living ones, which could potentially be vulnerable to disease and dissolution due to warming water temperatures and increasing ocean acidity. McGillis will place an array of instruments that he has invented in the living reef to measure corals’ metabolisms in real time, and the rates at which they build their skeletons vs. the rates at which the skeletons dissolve. He has had identical instruments at reefs in La Parguera Bay, Puerto Rico since 2007, and at the Cheecha Rocks reef in the Florida Keys since 2011. At these latter reefs, which are more affected by nearby human activity, McGillis and staff associate Diana Hsueh visit to download data every 3 to 4 months; their next visits there will be in March 2014. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has asked McGillis to look into manufacturing the instruments on a larger scale so they can be used to also monitor sea grass, mangroves and bottom mud in various places. Related: Line Islands Corals

ARCTIC CLIMATE HISTORY Lake coring/mapping Svalbard, Norway, AUG 24-SEPT 8, 2014

Arctic glaciers are receding fast due to global warming. With the aim of putting their retreat into the context of the last 10,000 years, researchers will travel by ship and foot to collect sediment cores from lakes on the north side of the barren Svalbard islands. Minerals in the sediments can tell scientists when glaciers expanded into the lake valleys and when they withdrew. Tiny remnants of algae and other plants can tell them how temperatures varied and how wet the sites got. University of Bergen researcher Jostein Bakke will lead the field expedition, joined by Lamont climate scientists William D’Andrea and Nicholas Balascio. The team will sail the 300 miles from Longyearbyen to Nordaustlandet, with stops to disembark and core lakes by raft along the way. There may be a chance for visitors to disembark early, around Sept. 2-3. (Team members will stand guard with rifles in case of polar bears.) Related: Story on D’Andrea’s previous work in Svalbard

ICE AND FIRE: IS THERE A CONNECTION? Deep-sea coring, lava sampling, U.S. Pacific Northwest AUG-SEPT 2014

Ice ages have waxed and waned for millions of years, and so, maybe, have volcanic eruptions, on roughly the same scale. Could the two processes be related? The Volcanoes, Ocean Ice and Carbon Experiments (VOICE) project has an overarching hypothesis: When vast amounts of water build up into landbound ice sheets, volcanoes there get stopped up by the pressure; but there is a corresponding drop in sea level that allows more volcanically driven undersea hydrothermal vents to let loose. Then, when the planet warms to remove ice and raise sea levels, hydrothermal venting is tamped down, while land volcanoes become more active. The complimentary processes, which release CO2 during eruptions in either realm, may help regulate global climate in a seesaw fashion. In a cruise of the U.S. Pacific Northwest aboard the R/V Atlantis, an international team of researchers including geochemist Jerry McManus will drill into sediments holding geochemical tracers of past hydrothermal eruptions, to see if these have varied in relation to ice ages. Around the same time, former Lamont postdoc David Ferguson (now at Harvard) and others will sample and date old lavas in the Cascades Range of Washington, Oregon and California to get at the land end of the equation. VOICES is a collaboration of scientists at Lamont-Doherty, Harvard, Penn State and universities in Germany and the U.K. The research could even suggest whether the world may experience an uptick in volcanic eruptions now, as climate warms. Other Lamonters helping lead the project: Suzanne Carbotte, Joerg Schaefer and Gisela Winckler. Related: VOICE project / Chronicle of Higher Ed feature on volcanism and climate

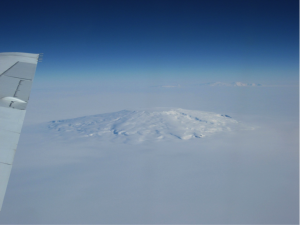

POLAR ICE FROM ABOVE Aerial Surveys, East Antarctica OCT-NOV 2014

Climate change appears to be affecting the ice sheets of West Antarctica and Greenland from both above and below, as both air and ocean waters warm. To understand the processes, the NASA-led Operation IceBridge has been imaging the ice sheets in three dimensions, using instrument-laden aircraft flown at low levels. This year the project moves to the vast East Antarctic ice sheet, where a NASA P-3 plane will fly grid lines with a laser altimeter, radars, optical camera and instruments that measure gravity and magnetics. Lamont crew members Kirsty Tinto and Jim Cochran will be responsible for the latter two suites of instruments. Flights will be based out of the U.S. McMurdo Station. The instruments measure parameters including ice thickness and shape of underlying bedrock, shedding light on how the ice is changing, and why. Related: Lamont’s IceBridge website / NASA IceBridge website and NASA IceBridge logistics pages / Greenland expedition blog and Antarctica expedition blog

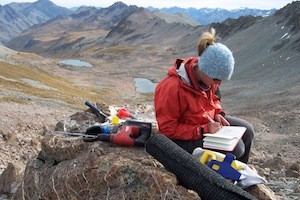

ANDEAN ECOLOGY AND CLIMATE High-elevation surveys, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru ONGOING (every 3 months; next, MARCH 2014)

The high Andes hold some of the world’s most diverse ecosystems; but climate change may be destabilizing them, as well as water resources critical to major cities below. Since 2004, scientists led by Colombia-based Daniel Ruiz Carrascal of the International Research Institute for Climate and Society have worked in Los Nevados Natural Park, near Medellin, at 4,000-4,500 meters. There, clouds and humidity are thinning, water bodies drying, and wildfires increasing; stressed plants and other biota may be moving toward summits. One-week surveys of biota and collections of data from a network of permanent instruments are done about every three months. In northwest Bolivia, between the towns of Antiquilla (4,600 meters) and San Jose (520 meters) temperature/humidity loggers have also been installed, and surveys are conducted periodically. In Los Nevados, along the Colombia-Ecuador border, and in the Madidi-Apolobomba protected area of Bolivia and Peru, Lamont tree-ring scientist Laia Andreu Hayles is also working with Carrascal to develop chronologies of past climate using high-elevation trees and woody plants. Participants must acclimate to extreme elevations, and endure inclement weather. Related: Watch a slideshow on the project / Los Nevados flora catalog, image gallery (Spanish) / Project blog post / Video on related study of Andean glaciers

100 MILLION YEARS OF CRISES Deep coring, geologic reconnaissance, U.S. Four Corners region LATE 2014 and BEYOND

The Four Corners area of the American West is a paradise for geologists and paleontologists, with its spectacular rock formations, canyons (including the Grand Canyon), and rich fossil beds. However, many layers remain inaccessible on sheer cliffs, or deeply buried. Thus, no continuous, well-dated chronology exists for key geologic periods. To assemble a conclusive timeline, Lamont geologist Paul Olsen, paleomagnetics expert Dennis Kent and colleagues are leading the Colorado Plateau Coring Project, aimed at drilling cores as much as 1.5 kilometers deep from a half-dozen sites. They are seeking data from 250 million to 145 million years ago, a time of great planetary changes: the ascent of dinosaurs, origins of modern ecosystems, and repeated extinctions of much life on earth. The first cores were taken in November-December 2013 at Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park. These penetrated the colorful, fossil-rich Chinle and Moenkopi formations, spanning the late Triassic, about 235 million to 202 million years ago–the era leading up to a mysterious global extinction that cleared the way for the rise of the dinosaurs. Among other things, the cores are expected to illuminate how large natural climate swings driven by the movements of earth perturbed life on earth over long periods—and shed light on what changing climate might do now. Scientists will also examine evidence that a giant meteorite that hit what is now Canada preceded the mass extinction that led to the dinosaurs. The cores should allow scientists to refine their understanding of similar records from the same era in other sites across the world. The team will be scoping out future drill sites, and possibly drilling again this year. Related: Multimedia package on the project (coming soon) / CPCP website / Related fieldwork in the United Kingdom / Article in Nature about the project / Discover magazine visits the project / CPCP facebook page