Sailing into a Storm as We Head for the Agulhas Plateau

The team aboard the JOIDES Resolution just finished at their first coring site off southern Africa. The first results? “Awesome.” Sidney Hemming describes the process in words and photos.

Read Sidney Hemming's first post to learn more about the goals of her two-month research cruise off southern Africa and its focus on the Agulhas Current and collecting climate records for the past 5 million years.

We finished up at our first core site yesterday, and now we are steaming south toward the Agulhas Plateau. The groups presented their summaries this morning, and the results from this site are awesome.

Inevitably there is a gap between each sediment core because of how the cores have to be taken. The drilling crew drills down to the level of the previous core's penetration and then sends the piston core down again. There are potential coring artifacts, such as "suck-in" of sediment at the bottom, "fall-in" of sediment at the top, or loss of sediment because the core catcher didn't catch. That is the reason for triple—and in this case quadruple—holes at each site. The stratigraphic correlators, Steve Barker and Chris Charles, take data from the physical properties measurement tracks and work fast to determine how the cores that are coming up can be correlated to previous cores. They find the gaps and work with the drillers to ensure that the gaps from all the holes do not overlap. With the help of the lithologic description team, they also avoid parts of the core that have been disturbed by the drilling.

At the Natal Valley site, the correlators were able to achieve a continuous splice going back more than 5 million years! We obtained samples older than that, but they are "floating." The splice, like it probably sounds, uses the overlapping physical features in the cores to identify a combination of cores that, when pieced together, yield a full continuous record. This splice is where most of the sampling and measurements will be conducted at the post-cruise sampling party. That will probably take place in September to give enough time for the cores to be shipped to Texas A&M and, we hope, scanned with an XRF scanner in order to construct the best sampling plan.

Image Carousel with 10 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: The team aboard the JOIDES Resolution collected the first four cores of Expedition 361 from the Natal Valley site. Here, scientists prepare to open the first. (Tim Fulton/IODP)

-

Slide 2: To drill down into the sea floor, the ship uses a large rig and a professional drilling crew. ( Jens Gruetzner, Alfred-Wegener-Institut for Polar and Marine Research)

-

Slide 3: Professional rig personnel bring the first core aboard. Each segment is 9.5 meters long and is sectioned into smaller pieces for analysis and storage. (Tim Fulton)

-

Slide 4: Scientists work the core catcher, which holds each segment of core in as it lifted from the sea floor. (Tim Fulton)

-

Slide 5: Once the cores are split, they are photographed in shipboard imaging equipment called a Section Half Image Logger. (Tim Fulton)

-

Slide 6: The shipboard labs are ready for scientists to go to work. Kaoru Kubota of the University of Tokyo and Xibin Han of China work on reports in the core lab. (Tim Fulton)

-

Slide 7: Sedimentologists Julien Crespin of the University of Bordeaux and Alejandra Cartagena-Sierra of Notre Dame take down descriptions of the core. (Tim Fulton)

-

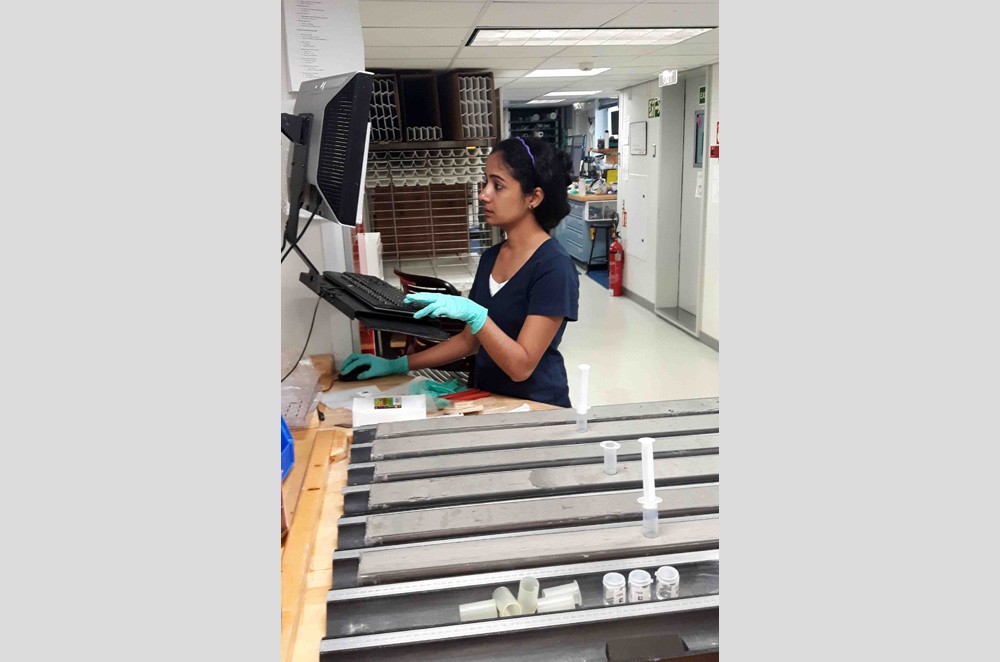

Slide 8: Nambiyathodi Lathika, a physical properties specialist from India's National Centre for Antarctic and Ocean Research, enters core data at the sample table. (Jens Gruetzner)

-

Slide 9: Jeroen van der Lubbe of the University of Amsterdam works with a cyrogenic magnetometer to analyze the magnetic properties of a sample. (Jens Gruetzner)

-

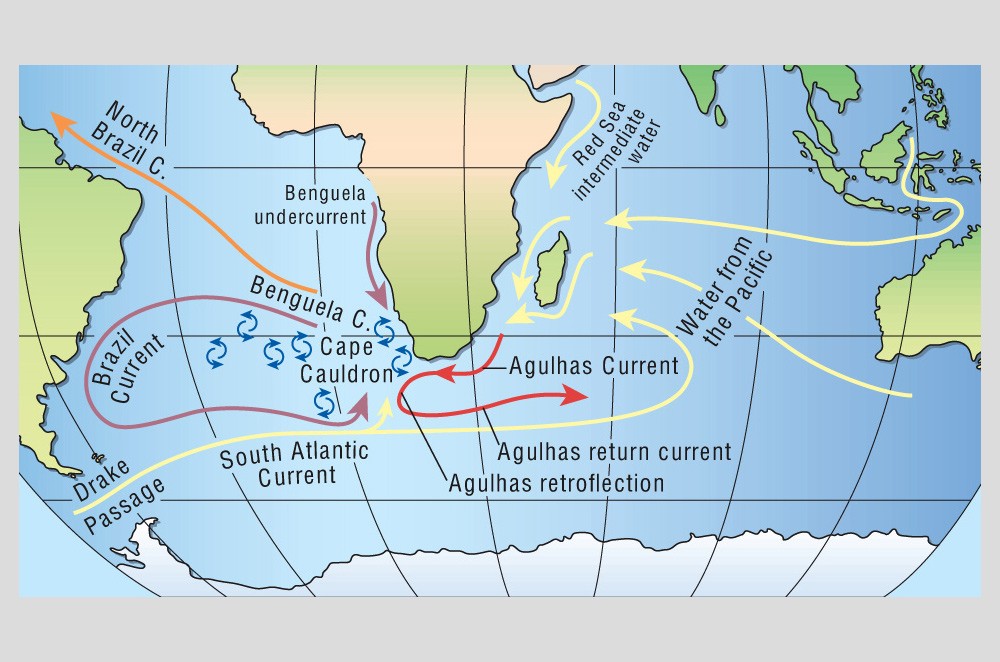

Slide 10: A map of the Agulhas Current, which the scientists of Expedition 361 are studying along with southern Africa's climate history. (Courtesy of Arnold Gordon)

The team aboard the JOIDES Resolution collected the first four cores of Expedition 361 from the Natal Valley site. Here, scientists prepare to open the first. (Tim Fulton/IODP)

To drill down into the sea floor, the ship uses a large rig and a professional drilling crew. ( Jens Gruetzner, Alfred-Wegener-Institut for Polar and Marine Research)

Professional rig personnel bring the first core aboard. Each segment is 9.5 meters long and is sectioned into smaller pieces for analysis and storage. (Tim Fulton)

Scientists work the core catcher, which holds each segment of core in as it lifted from the sea floor. (Tim Fulton)

Once the cores are split, they are photographed in shipboard imaging equipment called a Section Half Image Logger. (Tim Fulton)

The shipboard labs are ready for scientists to go to work. Kaoru Kubota of the University of Tokyo and Xibin Han of China work on reports in the core lab. (Tim Fulton)

Sedimentologists Julien Crespin of the University of Bordeaux and Alejandra Cartagena-Sierra of Notre Dame take down descriptions of the core. (Tim Fulton)

Nambiyathodi Lathika, a physical properties specialist from India's National Centre for Antarctic and Ocean Research, enters core data at the sample table. (Jens Gruetzner)

Jeroen van der Lubbe of the University of Amsterdam works with a cyrogenic magnetometer to analyze the magnetic properties of a sample. (Jens Gruetzner)

A map of the Agulhas Current, which the scientists of Expedition 361 are studying along with southern Africa's climate history. (Courtesy of Arnold Gordon)

We still do not have permission to drill in Mozambique waters. This is causing considerable anxiety for the team, and by steaming south, we will definitely not be able to drill our northern-most planned site. However, if permission comes before we finish the Agulhas Plateau site, we could still meet our Zambezi and Limpopo objectives. The Zambezi and Limpopo are major rivers that drain from the African continent. We hope to capture sediment coming from those two rivers to answer questions about rainfall and runoff and weathering.

The Agulhas Plateau is also an exciting site. It is a little bit north of the sub-tropical front, which is the northern boundary of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Today, it is under the Agulhas retroflection, where the Agulhas Current swings back toward the east (see the map at the end of the slideshow). Our goal is to understand how the position of the sub-tropical front and the Agulhas retroflection have changed through the last 5 million years, and how those changes are related to climatic variability in southern Africa.

Allison Franzese's Ph.D. research used a time-slice approach to compare the modern composition of sediments washed in from the continents with those deposited during the last glaciation about 20,000 years ago (ice at that time covered what today is New York City). She has suggested that the path of the Agulhas retroflection was very similar between modern and glacial times. Her results are enigmatic because they indicate both a weakening of the current and a similar path for the retroflection, and these observations are inconsistent with what is predicted from physical oceanographic modeling. The cores we collect here should allow her to extend her studies back to 5 million years and achieve a much greater understanding of how the system has worked under a range of climate conditions, particularly when combined with results from the Natal Valley site and the Cape site (the final site of the cruise).

As an aside, I am pretty pleased that even though we are sailing through a storm with about 30 knot winds right now and the ship is swaying, I'm still feeling pretty good. Apparently this could change—we are heading toward the "roaring 40s."

Sidney Hemming is a geochemist and professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. She uses the records in sediments and sedimentary rocks to document aspects of Earth's history.