New Study Pins Time of Greenland's Last Melting to Some 400,000 Years Ago

A study adds evidence that the Greenland Ice Sheet will be vulnerable to human-induced climate change in coming centuries.

In 2016, a groundbreaking study of a unique bedrock core drilled from under the center of the Greenland Ice Sheet suggested that most or all of the ice covering the landmass had melted away at least once during the last 1.1 million years. In 2021, a study of another core containing sub-ice sediments laden with plants from a site 500 miles away reached a similar conclusion. The pair of studies helped overturn a previous view that the ice sheet has been stable for millions of years, even during naturally warm periods. It also strengthened the prospect that human-induced warming could eliminate the ice sheet, which holds some 23 feet of potential sea-level rise.

Researchers now say they have more precise timing for at least one such melting event. A new study in the journal Science says a large portion of Greenland turned to ice-free tundra about 416,000 years ago, plus or minus 38,000 years—quite recent in geologic time. They calculate that the melting caused at least five feet of sea level rise—and maybe as much as 20 feet—at a time when temperatures were only slightly warmer than today, even though atmospheric levels of heat-trapping carbon dioxide were far lower. This indicates that the Greenland ice may be more sensitive to human-caused climate change than previously understood, and could be vulnerable to irreversible, rapid melting in coming centuries.

The scientists, from the University of Vermont, Columbia University and other institutions, used sediment from the bottom of a long-lost ice core, collected at a secret U.S. military base in the 1960s, to make the discovery. They applied advanced luminescence and isotope techniques to provide direct evidence of the timing and duration of the ice-free period.

“A big remaining question following [the previous studies] was when was the most recent exposure?” said study coauthor Sidney Hemming, a geochemist at the Columbia Climate School’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “This is a strong case. It was a serendipitous opportunity to probe the history recorded in the sediments.”

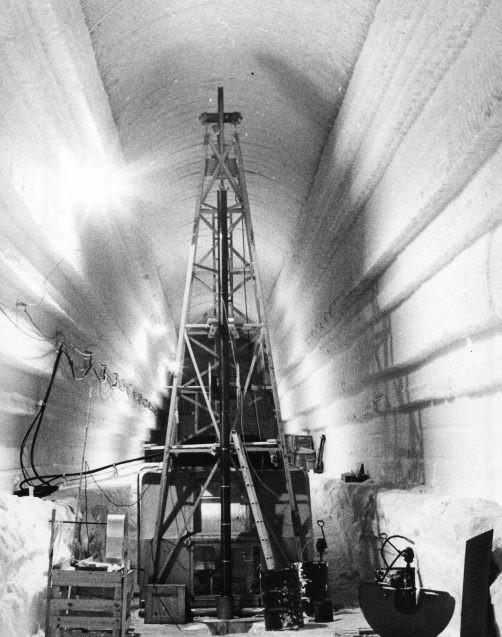

The study site, called Camp Century, is in northwest Greenland, 138 miles inland from the coast and only 800 miles from the North Pole. One purpose of the Cold War camp was to secretly station hundreds of nuclear missiles near the Soviet Union. As cover, the Army claimed it was a science station.

The missile mission was a bust, but a science team there completed important research, including drilling an ice core 4,560 feet deep. Then they kept going, to pull out a 12-foot-long tube of soil and rock from below the ice. The scientists at the time took little interest in the sediments; the core was moved in the 1970s from a military freezer to the University at Buffalo, then to a freezer in Denmark in the 1990s. There it was forgotten, until it was examined in 2017. The findings, published in 2021, showed it held not just sediment but leaves, moss and other detritus of things living on the surface—remnants of an ice-free landscape, perhaps a boreal forest.

But how long ago were those plants growing there, where today there is an ice sheet three times the size of Texas and as much as two miles thick? The new study presents evidence that the sediment just beneath the ice sheet was deposited by flowing water in an ice-free environment during a moderate warming period called Marine Isotope Stage 11 lasting from 424,000 to 374,000 years ago, when temperatures were slightly warmer than today.

“It’s really the first bulletproof evidence that much of the Greenland ice sheet vanished when it got warm,” says University of Vermont scientist Paul Bierman, who co-led the new study with Drew Christ, a post-doctoral geoscientist who worked in Bierman’s lab.

Joerg Schaefer, a geochemist at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory who helped lead the previous two studies but was not involved with the current paper, said he was not surprised that the researchers zeroed in on this time period. “Clearly we have considered MIS 11 a contender, because it was one of the warmest periods,” he said. Still, he believes more work is needed to really prove the case. He is currently helping lead Project GreenDrill, a massive U.S. National Science Foundation-funded effort aimed at doing just that. The project will drill four new bedrock cores from around Greenland, which will be intensively studied in order to better document the recent melt history of Greenland. The team brought up its first core this summer.

Understanding Greenland’s past is critical for predicting how its giant ice sheet will respond to climate warming in the future. “Greenland’s past, preserved in 12 feet of frozen soil, suggests a warm, wet, and largely ice-free future for planet Earth unless we can dramatically lower the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere,” said Bierman.

The sediment core in the new study was examined for a so-called luminescence signal in Tammy Rittenour’s lab at Utah State University. As bits of rock and sand are transported by wind or water, they can be exposed to sunlight, which, basically zeros out any previous luminescence signal, and then reburied under rock or ice. In the darkness, over time, minerals of quartz and feldspar in the sediment accumulate freed electrons in their crystals.

Rittenour’s team took pieces of the ice core sediment and exposed them to blue-green or infrared light, releasing the trapped electrons. The number of released electrons forms a kind of clock, revealing with precision the last time these sediments were exposed to the sun.

The new luminescence data were combined with data from Bierman’s lab. There, scientists studied quartz from the core. Inside this quartz, rare isotopes of the elements beryllium and aluminum build up when the ground is exposed to the sky and can be hit by cosmic rays. Measurements of the ratios of such isotopes to one another can tell scientists how long rocks at the surface had been exposed versus buried under layers of ice. These data helped the scientists show that the Camp Century sediment was exposed to the sky less than 14,000 years before it was deposited under the ice, narrowing down the time window when that portion of Greenland must have been ice free.

Although the period when this happened is thought to have been only slightly warmer than today, there was far less carbon dioxide in the atmosphere then—280 parts per million or less, versus 420 parts per million today and rising. The findings confirm the fragile nature of the entire Greenland ice sheet, the scientists said.

“Forward modeling the rates of melt, and the response to high carbon dioxide, we are looking at meters of sea level rise, probably tens of meters,” said Rittenour. “Then look at the elevation of New York City, Boston, Miami, Amsterdam. Look at India and Africa—most global population centers are near sea level.”

“Four hundred thousand years ago, there were no cities on the coast,” said Bierman. “Now there are cities on the coast.”

Based in part on a press release from the University of Vermont.