Learning How Trees Can Help Unlock Secrets of Our Climate Future

A new cataloging system will help better preserve, track and share thousands of tree ring samples from around the globe.

You may know you can gauge the age of a tree by counting its rings. But did you know that tree rings can help researchers predict future changes in climate?

Students at Lamont-Doherty’s Tree Ring Lab (TRL) are currently engaged in this work, in a field of study called dendrochronology: the scientific study of tree rings and the variation of growth patterns through time. Researchers can analyze tree rings to reconstruct historical climate phenomena and to predict future conditions in an associated field of study, dendroclimatology.

This past summer, Olivia Colton and Tyler Zorn, graduate students in the Master of Science in Sustainability Science program, worked as laboratory assistants to facilitate the transition to a new specimen and data-cataloging system at the TRL. This system is meant to better preserve these records and share them with the global community.

Why is this work so significant? Tree rings record environmental changes through time, which can be interpreted by understanding the way trees grow. Each year a tree lays down a new layer of growth, or ring, around its trunk. Generally speaking, in good years—when trees grow well—the rings are wide, and, in bad years, the rings are narrow. Research being conducted at the TRL currently focuses on the use of tree-ring data networks to advance our knowledge of regional climate and inform mitigation and adaptation strategies.

The Tree Ring Lab was established by Ed Cook and Gordon Jacoby in 1975, and is currently home to thousands of tree ring samples from around the world. The TRL is a prominent international leader in research, training and technology in dendrochronology. The research being conducted at the TRL currently focuses on the use of tree-ring data networks to advance our knowledge of regional climate and inform mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Aside from being a valuable source of environmental information, tree rings can also provide insights into the archaeology and history of wooden artifacts. How old is the wood used in a historic structure? Where did it come from? A great example is the mysterious ship found below the World Trade Center site in 2010, which was identified and cataloged by the TRL as white oak and dated to 1773 in colonial-era Philadelphia.

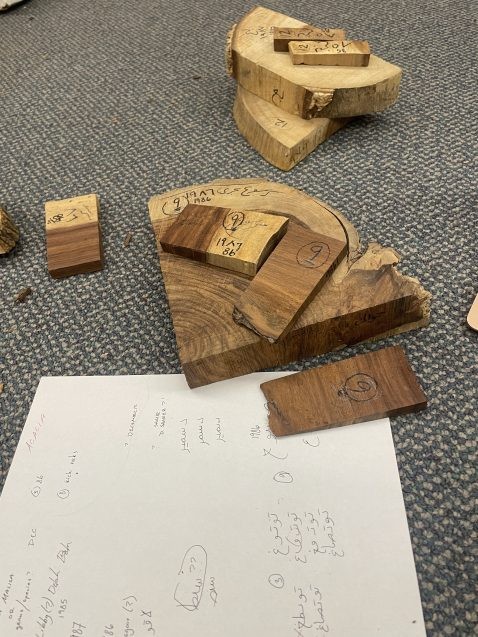

There are two main processes to properly collect and analyze the rings of a tree: extracting tree cores and taking a cross section of a tree’s trunk. In core extraction, a specialized tool, known as an increment borer, is screwed into the side of a tree until it penetrates past the center. An extractor is then inserted into the borer, and the extractor and borer are removed, allowing a tree core sample to be collected. The trees are not harmed in the process, but only certain types of trees can be sampled this way. The cross-section approach is typically used on fallen or dead trees to avoid unnecessary harm to living ones. Cross sections are much larger in size, which makes them more difficult to store, organize and catalog. The TRL is home to thousands of tree core and cross-section samples from countless research excursions.

Colton and Zorn’s laboratory responsibilities at the TRL this summer involved cataloging over 1,600 cross-sections collected from field studies across the globe: including Tasmania, Australia; Kotzebue, Alaska; Labrador, Canada and Central Mongolia. This process included measuring, photographing, labeling and organizing the samples based on their geographic origins.

They also recorded details about the samples in the System for Earth Sample Registration (SESAR), a community platform that provides access to a global digital index of samples, specimens and related sampling features. There are over 4 million records in the SESAR catalog, as well as over 1,000 users of the system. As an allocating agent of the International Generic Sample Number (IGSN), SESAR offers globally unique and persistent identification of samples that makes the data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR). This enhanced system also allows users to access a QR code to view a photo of the sample, its location, and any further details that might be available (e.g., the precise location of a sample or whether the tree was living or dead when it was collected).

By contributing to this global database, TRL’s intention is to increase the accessibility of these samples to anyone interested in using them for future research.

There are still several hundred cross-section samples to catalog and organize. As Colton and Zorn return to Columbia’s main campus this fall to continue their full-time studies, the TRL hopes to find new part-time laboratory assistants to carry on this important work.

Interested in getting involved at the TRL? Graduate students can contact Lamont Research Professor Brendan Buckley ([email protected]) for more information.

The Master of Science in Sustainability Science program, offered by the School of Professional Studies in partnership with the Climate School, is designed for current and aspiring leaders who wish to help organizations understand the technical aspects of sustainability, including predicting and addressing environmental impacts.