Drilling the Seabed Below Earth’s Most Powerful Ocean Current

Starting this month, scientists aim to study the Antarctic Circumpolar Current’s past dynamics by drilling into the seabed in some of the planet’s remotest marine regions.

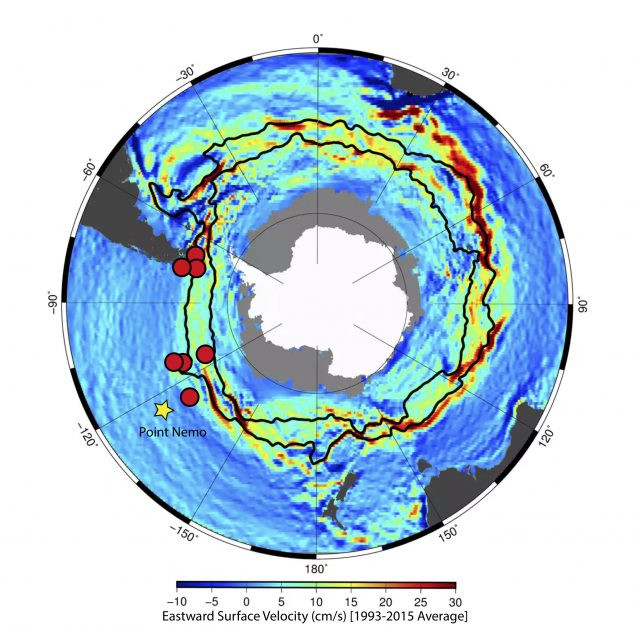

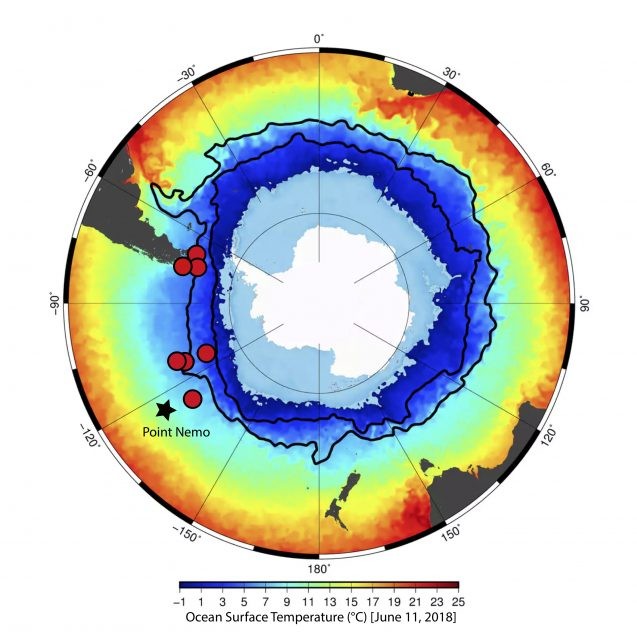

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current is the planet’s most powerful and arguably most important. It is the only one to flow clear around the globe without getting diverted by any landmass, sending up to 150 times the flow of all the world’s rivers clockwise around the frozen continent. It connects all the other oceans, and is thought to play a key role in regulating natural climate swings that have repeatedly swept the earth for millions of years. But much is still not known about how it works, including how it might now respond to human-induced climate change.

Starting this month, some 30 scientists from 13 countries aim to study the current’s past dynamics by drilling into the seabed in some of the planet’s remotest marine regions. They will sail May 20 from Puntas Arenas, Chile on the ship JOIDES Resolution, to begin Expedition 383 of the International Ocean Discovery Program. The IODP is a collaboration of scientists from around the world that studies the history of the earth as recorded in sediments and rocks beneath the ocean floor.

“This is really a key piece of the world climate system, because this is where so much heat and carbon are exchanged between the ocean and the atmosphere,” said the cruise’s co-chief scientist Gisela Winckler, a geochemist and paleoclimatologist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “We should learn about how the winds, the ocean and the Antarctic ice sheet have responded to warming in the past. That will help us know what they might do in the future.”

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current, or ACC, as scientists call it, is actually a complex set of currents. Spinoffs from it balloon huge amounts of long-stored carbon dioxide, nutrients and heat up from the deep ocean. Interactions with the air and sunlight may result in big blooms of phytoplankton, some of which rain back into the depths. But some CO2 also leaks back into the atmosphere. The balance between these two processes and others can change over time; this in turn can change the CO2 content of the atmosphere, and thus the planet’s temperature. The ACC is thought to help store more CO2 in the ocean during cold periods, and less during warm ones. Now that we are entering an artificially warm period driven by human emissions of CO2, how will the ACC react? Will it blunt the warming, or turn it up even more?

To investigate what has happened in the past, the scientists will drill into sediment lying from 1,000 to 5,100 meters under the sea surface, and bring up cores up to 500 meters long. The first, shallower cores will come from the continental shelf along the southernmost coast of Chile, where the ACC must pass through the relatively narrow Drake Passage between South America and the Antarctic peninsula. Later cores will come from the southeastern Pacific, near the oceanic pole of inaccessibility. Also known as Point Nemo, this is the spot in the ocean farthest from any land–more than 1,000 miles in any direction. “That is kind of cool, and terrifying,” says Winckler.

The cores are expected to contain shells of tiny creatures that died and sank to the bottom as far back as 8 million years ago. These encapsulate information about ancient water temperatures, plankton production, nutrient concentrations and other qualities that would help chart changes in the ACC’s strength and other workings. Some cores from the southeast Pacific may also contain rocky debris scraped up by glaciers in Antarctica, rafted out to sea in icebergs, and then dropped to the bottom when the bergs melted. Changes in such debris over time would allow the researchers to see how the ice sheet reacted to cold and hot swings hooked into the ACC.

Cores drilled off Chile should contain sediments blown or washed directly from land, and built up far more rapidly than those from the deep sea. These might allow the researchers to read the causes and effects of climate switches on scales of just millennia, or even centuries–eyeblinks in geological time that most other marine records cannot produce.

One current mystery: for reasons that are not well understood, the powerful winds from the west that drive the ACC’s clockwise motion have increased in recent decades; yet the ACC itself has not become any stronger as a result. The coring may help the scientists test hypotheses about why this is so.

The cruise “will provide important information for more accurately forecasting the rate and magnitude of future global climate change related to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels,” said Jamie Allen, program director at the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences, which supports the IODP.

The other co-chief scientist on the cruise is Frank Lamy of Germany’s Alfred Wegner Institute. Along with several postdoctoral researchers from Lamont-Doherty, the scientific party will also include researchers from Japan, the United Kingdom, South Korea, Italy, China, Brazil, France, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Spain and India.