Anatomy of an ‘Ice Station’

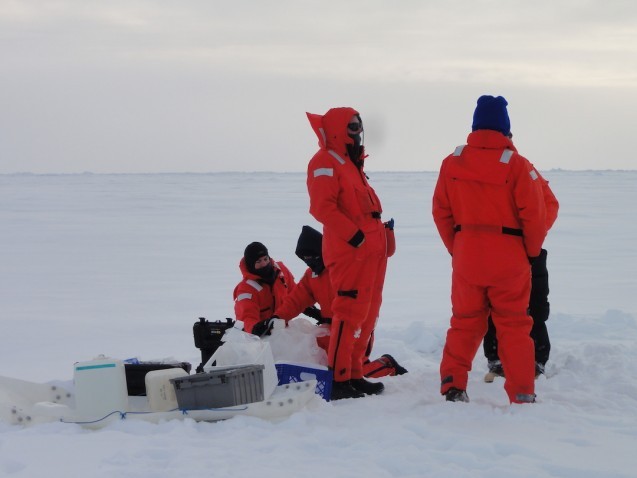

Completing an “Ice Station” means collecting samples over a wide range of Arctic water and ice conditions. Each station means a major orchestration of people and resources.

Completing an “Ice Station” means collecting samples over a wide range of Arctic water and ice conditions. Each station means a major orchestration of people and resources. The teams gather, equipment is assembled, and the trek off the ship begins. After the first off-ship exodus, the sample teams are well practiced in moving equipment and setting up work areas so as not to interfere with the other stations. There is no shortage of space so spreading out is not a challenge!

Collecting a wide range of samples at multiple Arctic locations allows GEOTRACES to get an integrated look at the trace elements moving through the Arctic ocean ecosystem, and to better understand how these elements connect to the larger global ocean. Each is carefully collected. Whether the elements are “contaminants” or essential nutrients, there is a specific protocol in order to quantify the inputs without “dirtying” the sample. It may seem odd to think of “dirtying” something we label a contaminant, but in order to fully understand the concentrations and methods of transport for each element, every sample is handled with the same amount of care.

The following photo essay showcases the various ice/water sampling stations and reviews what is being collected at each.

Snow samples: The snow collected at this station is being used in part to determine the presence/absence of contamination related to the March 11, 2011, Fukushima event.

Both the snow samples and the ice core sections will be analyzed and examined along with the information collected from seawater, suspended particulates and bottom sediments, in order to better understand the influence of processes specific to the Arctic on the transport and distribution of several anthropogenic radionuclides.

Ice core samples: The ice cores are sections of sea ice, and again are being collected to determine the presence/absence of contamination related to Fukushima. In general the samplers were able to obtain 1.5 to 2 meters of ice in the cores.

Melt ponds: Surface melt ponds form on the sea ice in the long days of the Arctic summer. The warmth of the sun creates ponds that sit on top of the ice. The water collected in these ponds carries different properties than either the sea ice from which it melted, or the ocean water from which the sea ice formed. Most often these ponds have a frozen surface layer that needs to be drilled through before water is pumped out for collection.

Beryllium-7 (7Be) samples: Produced in the atmosphere when cosmic rays collide with nitrogen atoms, 7Be is constantly being added to the surface of the water, and therefore is a great surface water tracer. With its very short half-life, ~ 53 days, 7Be can be used to track water parcel circulation as it moves between surface and deep water (which has no significant source of the 7Be isotope). The surface water pulls the 7Be with it as it moves down deeper into the ocean, allowing us to track and time the mixing process.

Dirty ice samples: The dirty ice work is more opportunistic, and therefore is not part of each ice station. If dirty ice is spotted, it will be sampled, and while it may not be part of each ice station, it is part of the overall GEOTRACES protocol. While most of the stations sample for quantification, i.e. grams of sediment/ml ice, the dirty ice samples are used more for characterization, i.e. composition or mineralogy. For Tim’s work the collection of dirty ice is used to look at sediments originating from continental shelves bordering the Arctic, with the goal of evaluating or characterizing dirty ice as a transport vector for anthropogenic radionuclides.

Minimal processing of the samples collected at the stations will occur on the Healy. The snow and ice gets melted and the seawater acidified. The focus of the trip is to collect as much material as possible. There will be plenty of time for processing when the researchers are back at their home institutions.

Margie Turrin is blogging for Tim Kenna, who is reporting from the field as part of the Arctic GEOTRACES, a National Science Foundation-funded project.

For more on the GEOTRACES program, visit the website here.